During one of my first mixers after joining a sorority, a very drunk (and very predatory) frat boy called me a lesbian and tried to throw me out of the house after I pulled him off of my sorority sister. Another time, I was blatantly rejected from a party while they let in my friend. Both garishly dressed like provocative leprechauns for Saint Patrick’s day, the two of us only had one noticeable difference, that being our race—she is white, I am Asian. And that’s just the tip of the goddamn iceberg.

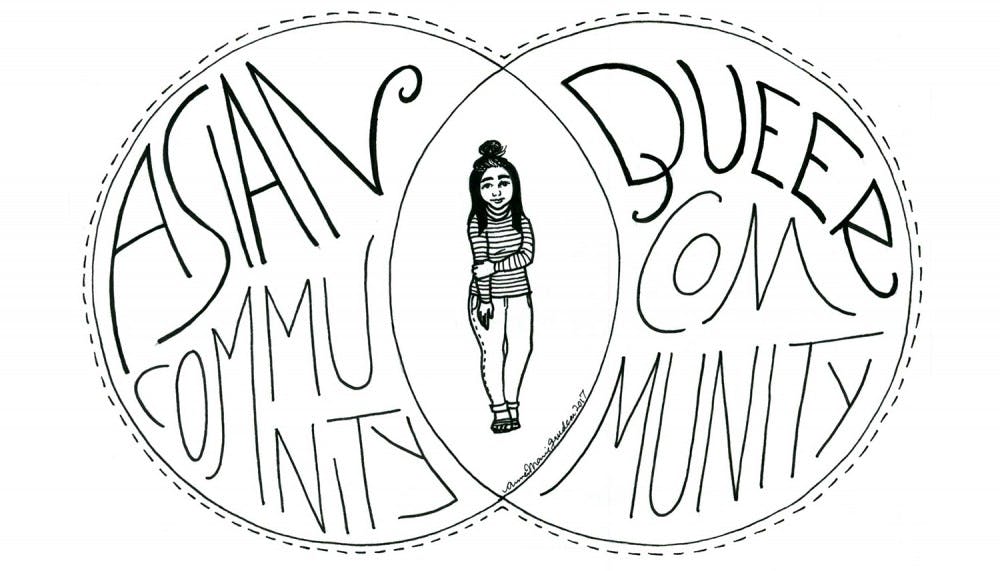

The word “intersectionality” is thrown around a lot as a buzzword these days. It refers to the way institutions such as race, gender, sexuality and disability coincide with one another. And it affects a lot of the experiences I have, especially at Penn. Being in a classroom or in a GBM and seeing faces that are so unlike mine is so tragically normal, but the worst part of it is that these places never reveal any intention to change to include me.

So if the system I am a part of constantly rejects so many fundamental dimensions of who I am, why am I a part of it?

My identity was never something I’d contended with before coming to college. In my safe little haven of Diamond Bar, California, we were all the same. Same zip code, same interests, same backgrounds. My neighborhood was homogenous in every sense of the word: ethnically, socioeconomically, politically. Everyone looked like me, dressed like me, talked like me.

Then, I got to Penn.

Penn, this supposed pillar of progressivism, where the social scene is predominantly Greek, straight and white. Have you noticed that most groups within the cultural houses don’t—for lack of a better word—fraternize with the predominant social scene? I did and assumed that it was a proactive segregation. Why couldn’t people like me at least try to fit in?

And that’s when the self–hatred began. I desperately wanted to belong, but I felt ostracized. People told me at parties, unwarranted, that they had a “thing for Asians.” I saw girls put chopsticks in their hair and drape bathrobes on themselves as kimonos for “Asian” mixers. I was told that I had to be “lucky” to be the “token Asian” of a pledge class. That is how I learned that I was seen as a caricature, a quota, a minority accessory to white populations on campus. That is how I learned I would have to accept such shitty treatment. I was a big, yellow splotch in a white space.

I’m going to come out (get it?) and say it: I’m bisexual. There aren’t a lot of openly queer women at Penn, and I never asserted myself as one of them. My sexuality was tucked away not out of convenience, but out of safety. It had made some friends feel uncomfortable and had revealed the dark biases of some others. I’m still haunted by the times I’ve hooked up with girls at parties to be met with the jeers of entitled, ignorant boys and the judging looks of other girls.

A safe space, according to Oxford Dictionaries, is “a place or environment in which a person or category of people can feel confident that they will not be exposed to discrimination, criticism, harassment or any other emotional or physical harm.” The idea of a “safe space” doesn’t exist for me. I have to stay racially neutral in most situations—dating, applying for jobs and everything in between—to avoid being tokenized, fetishized, commodified or all three. Since coming out would result in definite disownment, my parents might never know that their daughter occasionally dates women: a huge no–no in Chinese culture. The intersection of being queer and being Asian is like otherness raised to the second power. I am doubly sexualized as the submissive Asian bi chick, ready for both your threesome and your weird anime fixation.

So I joined a sorority as a reactionary device. I wanted to be a part of the overarching social scene at Penn. I glossed over my queerness and colored–ness through rush and during all the events that followed. Straightness was assumed: I talked only about the boys I was in love with and not all the girls. I ducked in hallways to speak Chinese to my parents: my ability to speak another language became a source of embarrassment, and occasionally a fun party trick.

I’m not trying to bash these institutions. Being a part of these different organizations has afforded me so many different experiences, and I’m appreciative of that. Yet, it felt like I couldn’t join a formal community that I completely fit into, so I found my own. I’m so grateful for the friends that I’ve found in cultural centers, Greek life and everywhere in between. Even though there aren’t a lot of queer women of color that I know, there are a lot of people who will listen to my experiences as one. And to me, that means everything and remedies most.

I’m still trying to define and navigate intersectionality for myself. I know I’m not the only one reconciling with these strange puzzle pieces that constitute this complex creature known as identity, these tricky parts that aren’t necessarily mutually exclusive. It’s getting less and less scary to just be who I am, so much so that I’m almost proud to be me. All of me.