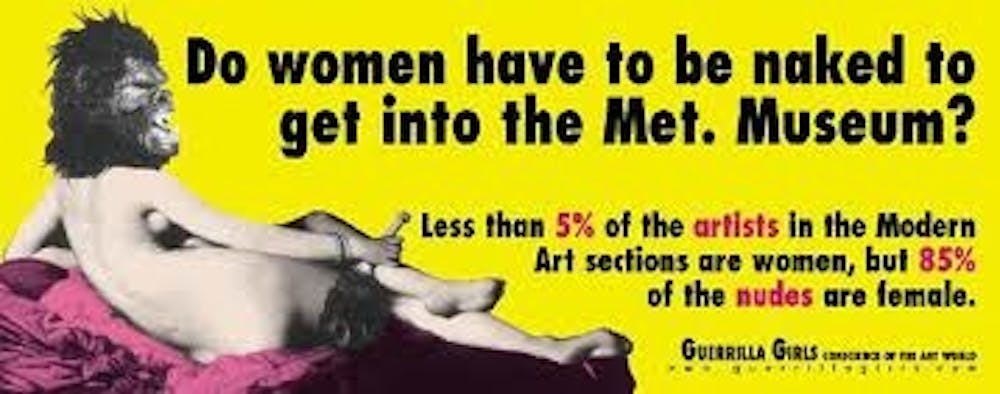

In 1989, a collective of feminist artists known as “Guerilla Girls” protested the lack of female artists in galleries through their most recognizable, provocative poster that inquired, “Do women have to be naked to get into the Met. Museum?” While the Public Art Fund of New York City originally commissioned their design for a billboard, the Fund rejected the Guerilla Girls' work after seeing it. The rejection demonstrated that mainstream, curated art spaces were not genuinely accepting of the narratives of women. Even in 2015, only eight percent of the artists on display in the Museum of Modern Art’s collections were women.

Now, though, women artists can force audiences to pay attention to the most intimate female experiences, using easily accessible platforms like Instagram to challenge conventional narratives of what womanhood entails. These emerging creatives focus on the performance of female sadness and reject how vulnerability in women is conflated with weakness. Not all women have professional success, a general state of happiness, or desire to upkeep a veneer of emotional strength. In a world that generally associates contemporary feminism with the notion of strong women who rebuff dependency, the visibility of sad women becomes a radical act in itself.

In an interview with Nylon Magazine, prominent visual artist and feminist theorist Audrey Wollen succinctly delineated “Sad Girl Theory” as the notion that “the sadness of girls should be witnessed and re–historicized as an act of resistance, of political protest.” She suggested that “protest doesn’t have to be external to the body. Girls’ sadness isn’t quiet, weak, shameful, or dumb: It is active, autonomous, and articulate. It’s a way of fighting back. The number–one cause of death globally for girls between 15 to 19 is suicide, and yet, [girls are told] that her sadness is individual and to keep quiet about it. Instead of trying to paint a gloss of positivity over girlhood, forcing self-love down [girls’] throats, feminism should acknowledge that being a girl in this world is one of the hardest things there is, and that sadness is actually a very appropriate reaction.”

Implementing this ideology into their artwork, artists like Molly Soda, Melissa Broder, Hobbes Ginsberg, and Vivian Fu blur the lines of accepted personal and public spheres of life to starkly show what women and gender–nonconforming individuals experience day–to–day. In many ways, “Sad Girl Theory” allows the most marginalized individuals to reclaim ownership of their identities. Asian–American artist Vivian Fu recalls growing up inundated with narratives of subordinate, “sidekick” Asian women. Through her own work, however, Fu visually documents her life, becoming her own protagonist. While these artists tend to use Instagram to display their visual and/or performance art, a growing number of “Sad Girls” use NewHive, an online platform for multimedia art. Through NewHive, artists can weave words, images, videos, and audio to express themselves. One artist in particular, Creepyennui, explicitly displays her body image issues and anxiety disorder through self–aware, ironic art on NewHive. In her most popular piece, It Isn’t Pretty After A While, Creepyennui layers an audio of her speaking about her anxieties concerning her figure with a video of her removing her makeup in bed. By viewing such private subject matter through the intimacy of one’s computer screen, the observer receives a glimpse into the lived experiences of the artist. It’s more personal than any art gallery outing.

While some consider such art mundane, “Sad Girl Theory” reminds us that using public platforms to document traditionally feminine emotions bravely oppose those who try to silence women’s sorrow. Though the Museum of Modern Art and other galleries have yet to truly prioritize women’s art, artists who epitomize “Sad Girl Theory” take the matter of representation into their own hands, imploring that their melancholy and art be acknowledged.