When Alec Druggan (C ’21), a staff photographer for the DP, moved to Philadelphia for his senior year of high school, he perceived that “in America, teenagers are much, much more sexually active than in other parts of the world.”

He experienced a bit of cultural whiplash. He is of Italian descent, was raised Roman Catholic, and spent his first three years of high school in Indonesia—the country with the largest Muslim population in the world.

His brief exposure to the Western approach to sex during his senior year may have helped him navigate Penn’s “hookup–centric” mentality. The campus culture also made him understand the importance of a comprehensive sexual education, especially in a large, varied country like America: “If you have no idea what you’re supposed to be responsible for, it’s really easy to get confused, which can lead to great mistakes.”

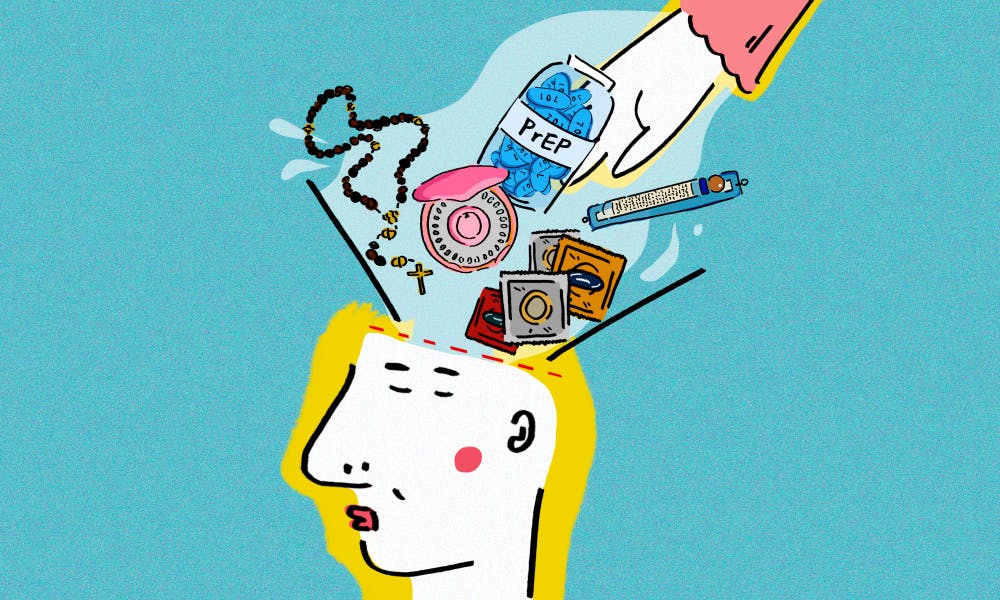

All Penn students come to college with varying degrees of experience and understanding when it comes to sex. And when sexual education is spotty or distorted, misinformation can spread—like Alec’s thought that American teenagers are much more sexually active, which isn’t really supported by any data. It’s not uncommon for high school sex ed to be muddled with religious notions, which can add another layer of confusion to sexual fumbles. This can make navigating Penn’s hookup–friendly, Tinder–swiping culture even more confusing for students, especially ones who must teach themselves about sex or unlearn what they were taught in high school. A 2016 Brandeis University study of Penn students found that 60% of the student body identifies as religious. Of the religiously affiliated students, 38% identify as Christian, 13% as Jewish, 4% as Hindu, and 2% as Muslim.

In Alec’s experience, sex ed in a religious environment is usually not an effective means of relating the realities of sex and sexual relationships. Although he attended an international school where health classes were mandatory in the tenth grade, Indonesia’s restrictive laws made it difficult for school to teach sex ed.

“We didn’t spend that much time on sexual education, but rather on drug–related stuff,” Alec recalled. “In the Muslim classes, they spent even less time on sex ed. From what I’ve heard, it was a lot more biased, and took a more religious approach.”

The University is aware that international students like Alec may have received different sex ed from their American peers, and tries to compensate.

“Every year, we have some type of outreach to international students,” Dr. Giang Nguyen, the Director of Student Health Services, said. “We recognize that students coming from other backgrounds might have very different exposure to health education overall, not just related to sexuality, but relating to healthcare in America in general.”

But in high school, it was ultimately the responsibility of his father, Alec says, to teach him about contraception, STI prevention, “and other stuff, like boundaries.”

However, students who don’t feel comfortable talking to their parents about sex can often only rely on sex education in school or their own piecemeal information before coming to Penn.

Despite growing up in a household which he describes as “very open and accepting of different types of people,” Mateo Fortes (N ‘19) notes that heterosexual parents might lack the experience needed to educate teenagers who are struggling with their sexual orientation.

“We never really spoke directly about sex—I wasn't willing to bring forth my concerns,” Mateo said about his relationship to his parents in high school. “It’s hard, when you have straight parents, because they've never had gay sex. There are so many things that they can't talk to you about.”

Growing up in Longmont, Colorado, Mateo felt isolated in a society that was “very religious, very conservative, and very, very heteronormative.” His parents’ progressiveness put him “on track to have liberal ideas,” but his religion played an important role in his life as well—he would go to church three or four times every week after having a Methodist confirmation in eighth grade.

While neither the guidance of Mateo’s religion nor his parents could alleviate his concerns about fitting in, he hoped that high school would solve that issue. But the health classes that his school provided to freshmen for one semester were ineffective. Not only did sexual education make up for only a small fragment of their curriculum, but their approach also failed to burst the heteronormative bubble.

“Queerness? Never, never, never, never, never. Not talked about. We never broke the boundaries of a heterosexual relationship. There just weren't people who identified as queer.”

Other students have found that sexual education which is even more overtly religious can not only be silent about certain topics, but use fear tactics to disparage premarital sex.

Sarah (W ’21), who requested that her last name be withheld, noticed this discrepancy in Judaism after starting a new high school as a sophomore. She transferred to the Ma'ayanot Yeshiva High School in Teaneck, NJ, which she describes as “a very religious, old–school, all–girl institution.” Indeed, she recalls, the school told the students to “wait until marriage—obviously, that’s the Orthodox way. In Orthodox Judaism you’re also not allowed to use condoms. It’s against the rules.”

However, the school’s mission to preach the values of Ahavat Torah (love of Torah) and Yirat Shamayim (fear of God) often gave way to what Sarah describes as a conflict of interests. “There was a disagreement between the teachers not wanting us to get STDs, but at the same time not wanting us to break the Jewish law.”

The professors decided to teach students about the dangers of unprotected sex, in particular with the help of graphic imagery—which Sarah remembers made the classes “a bit frightening.”

Rabbi Joshua Bolton of Penn Hillel recognizes that Jewish religious texts “could not conceive the sex lives our students are living.” He tries to address these gaps through a program called the Jewish Renaissance Project (JRP). “My primary role," he says, "is to create spaces where students can talk honestly and openly about boundaries.”

“The point of that is that the spiritual ideal of Judaism is not an abandonment of the body,” Rabbi Josh clarified. “Moreover, spiritual wisdom is not located only in the church, but also in other sacred spaces—especially in the bedroom, there is a possibility of discerning wisdom.”

But Rabbi Josh acknowledges that such open and relaxed discussions are not as common as they may seem. “What I said marks me as progressive, or liberal. There are definitely more conservative perspectives," he said.

Matt* (C’18), a student who attended a Catholic high school in Pennsylvania, says his high school's sexual education was reflective of the “more conservative” view. He found it not at all representative of the reality he faced while in college.

“There were three different ways they approached sex ed, but the one I particularly remember is Generation Life, which was probably the most delirious one. It was pure propaganda.” On its website, the group describes itself as a “dynamic movement of young people committed to building a culture of life by spreading the pro–life & chastity messages to other young people.”

“There’s this one statistic that they’d always use,” Matt says. “Non–lubricated condoms have a 16% failure rate, so they’d always push that forward. They had scare tactics.”

Even in health class—the only one described by Matt as “virtually non–religious”—the gravity of STDs was overshadowed by the need to avoid a pregnancy. Instead of embracing chastity, most students at his high school failed to see the point in using contraception in the first place. “People have sex all the time anyway, so there were quite a few pregnancies at my school," he said.

Although Matt’s sex ed was tainted by his school’s religious ethos, other students have found that religion and a healthy sexual culture are not oppositional.

Eliza Halpin (C ’20), who was raised in a Unitarian Universalist family, felt that her church–led programs educated her about sex and fostered an environment where she could eventually ask her mom for birth control. Less than one percent of the U.S. population is Unitarian Universalist, and Eliza smiles as she describes what the community means to her. “I was at this church my entire life, and this is the only religion my family has ever practiced.”

Eliza had her first encounter with sex ed in fifth grade, through a church–run program, but it wasn’t until eighth grade that she realized how different the Unitarian Universalist approach was. But the liberal, somewhat sentimental way in which the program was structured provided them with all the information they needed going into high school, along with condoms and lube.

“This version was unique because, unlike most classes, it was about the feelings involved with sex. A bunch of adults in the church come and sit with you, and tell stories of how they lost their virginity.”

With students such as Eliza and Matt arriving at Penn with such different levels of sexual education, it’s unclear if the onus is on Penn to educate its students about what they do on their extra–long twin mattresses. Matt judges that Penn fails to properly educate students. While SHS offers free condoms and pins eye–catching posters around campus, the administration still fails to acknowledge that such prevention methods require a basic understanding of sexual education, which some people lack. He recalls that, when an RA in a freshman hall was showing her residents where to get condoms, a girl looked at the bowl full of colorful, shiny packages, and thought they were candy.

“It’s sad. In an ideal world, by this age everyone should’ve gone through a system that has already hammered the idea of protected sex into their brains,” Matt said. “But I don’t know how Penn could solve that, and I don’t know if it’s the administration’s responsibility.”

Penn does boast piecemeal programming about sexual health, although students may not know where to seek it out.

“I would say that we’re really open to hearing from students, and I don’t really know what more we can do,” said Ashlee Halbritter, Director of Campus Health. “There is a sexual education module included in TAP [Thrive at Penn online program] that all incoming freshmen go through. Additionally, Campus Health does sexual health education in college houses and with student groups throughout the year. Every year, we hold a sex ed training for students who may be engaging in Greek Life, for their new members’ education. We’re certainly willing and able to do more, so we’d love to hear from students about what that looks like.”

As a delegate from her sorority, Sarah recently went to a Penn–sponsored sexual education event she found “super helpful.”

Isabella Fierro (C ’20) thinks the administration’s efforts to solve the issue do not suffice. “I haven’t learned a single thing from Penn,” she says.

As a former student at a small Catholic high school in California, she learned nothing about safe sex from her health classes. “The idea seemed to be that the only purpose of having sex was reproduction,” she laughs before she adds that her educators preached “affirmative hand holding” before marriage. There was also no mention of using contraceptive methods to prevent STDs, since that meant going “against God’s will.”

As a sophomore in college, she still wrestles with the contrast between her religious background and Penn’s hookup culture.

“I still wanted to be protected,” she said, “but I did experience a lot of Catholic guilt.”

Cătălina Drăgoi is a sophomore from Iași, Romania studying Political Science. She is 34th Street’s Film & TV Editor.