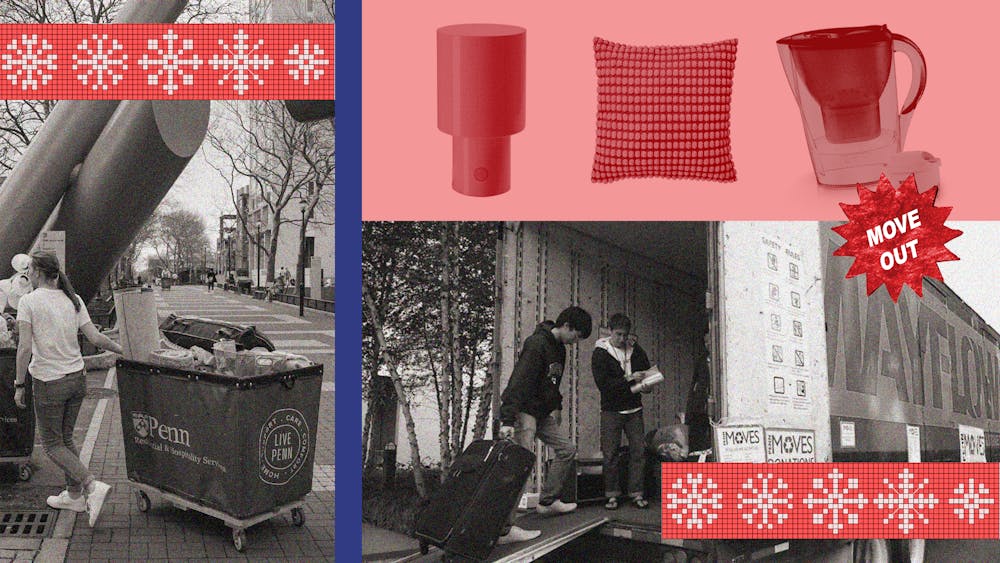

Mid–May is a season of endings on Penn’s campus. Seniors don cap and gown, final exams loom, and students buzz along Locust Walk cramming in final moments with friends before the school year ends. The familiar sights of family SUVs lining Spruce and Walnut streets, IKEA rugs spilling from trash bins lining the halls of residential houses, and parades of red–and–blue move–out carts rumbling across campus return. Outside of dorm rooms, abandoned lamps and tangled piles of string lights line the corridors like spotlights on a red carpet leading out of the school year and into summer.

While move–out signals closure for many Penn students, for others it marks something else entirely: opportunity. For some West Philadelphia residents, it’s “Penn Christmas”—a time when the abundant leftovers of campus life become a source of free furniture, appliances, and household goods. The phenomenon is well–documented and far from new, resurfacing each year in Reddit threads and neighborhood news articles, where locals trade tips on when and where to look for the best finds. Yet behind the chaos of move–out lies a complex system—one shaped by sustainability efforts, socioeconomic tensions, and a growing sense of responsibility from both students and the University.

For some Penn students, like Jaden Edens (C ’26), the experience offers a sobering view of “how rich some people are and how poor some people are.” Earlier this year, the rising senior volunteered for PennMOVES, a student–staffed, on–campus move–out program founded in 2008 that touts an average of 52,000 pounds of unwanted items donated to Goodwill each year. Jaden, who describes himself as “not necessarily that well off,” says that the value the items donated jumped out to him, from barely–used airfryers to new clothing. Still, he gets it. For the Penn students who are “accustomed to certain conditions where $100 isn’t the most in the world, and you’re just trying to hurry up and get home,” Jaden understands why some opt to donate those items. However, for people in surrounding neighborhoods, he adds, those same goods might hold more value.

“The fact that students are just wasting stuff, I think that’s just the nature of [their] median income,” Jaden remarks. In 2017, the median family income of a Penn student was $195,500—nearly five times higher than the median household income in the surrounding West Philadelphia neighborhood.

Jaden also recognizes his own hypocrisy and the crunch for time towards the end of the school year. “I critiqued people for donating something worth $150, but here I am dumping it out too,” he admits. After finals, faced with little time and mounting exhaustion, Jaden also tossed out items he would’ve saved otherwise.

Each year, Yiwen Zhan (N ’27) finds herself wondering how she managed to accumulate so many clothes and belongings. By the time the year ends, exhaustion sets in—especially as a nursing student with exams scheduled until the last day of finals period—and she admits she often just wants to “throw everything away at that point.” With limited time to sort through belongings, Yiwen believes students resign to tossing things out because it’s just more convenient. It’s not just about getting out, it's about getting out fast, and if speed means waste and mess, so be it.

Philly–local Brialis Phan (C ’28) acknowledged that unlike many of her peers, she didn’t need to cram everything into a single trip. She was able to move her belongings back home over the course of a few weeks without the pressure of an impending flight or train ride thousands of miles away from campus. Still, experiencing Penn move–out for the first time this spring was “bizarre” for Brialis, having come from a household where she was taught to “reuse things until they’re broken [and] there’s no longer a use for them.” While it makes her happy seeing local residents take what they want from the excess left behind, Brialis describes the phenomenon as “dystopian.”

“Penn is known for having a lot of students who come from wealthy backgrounds—not that that makes up 100% of Penn’s population, but it does make up a significant portion of it,” Brialis explains. “When you have people coming from the community that Penn is actively gentrifying coming in to take that stuff, it feels so weird. You can definitely see the wealth gap happening.”

The University’s strained relationship with West Philly has long been marked by displacement and institutional overreach. In the 1960s, Penn played a leading role in the destruction of the Black Bottom neighborhood, displacing over 7,000 residents to make way for dorms, shops, and academic buildings. Decades later, the demolition of the University City Townhomes reignited criticism of Penn’s continued role in reshaping West Philadelphia at the expense of longtime local residents for the benefit of its own students, programs, and profit.

Brialis explains that witnessing the amount of waste produced during move–out made her reflect on the mentality some of her classmates carry with them to campus.“Move–out just showed me how wasteful everyone was,” Brialis says. “I felt like there was just a sense of entitlement, people thinking they can throw out whatever they want, wherever they want, without even really considering if it could be used by someone else or if they could reuse it for next year.”

Still, Office of Social Equity and Community Director Scott Filkin sees it differently. Filkin has directed Penn’s off–campus move out initiative for the past three years, and to him, the growing volume of donations and increasing engagement with move–out programs reflects a student body that wants to do the right thing—but needs institutional support to do so.

While the University can’t control what students choose to buy, Filkin says it can influence what happens afterward when those items are discarded. When the right systems are in place, students generally make use of the resources available to them to minimize waste—or so Filkin believes. He might be right. This year, the on–campus program donated 67,865 pounds of unwanted items to Goodwill. Off–campus, more than 150 students utilized move–out services and generated over 670 donations—around 14,000 pounds of materials redirected through the University’s partnerships with community organizations.

Penn Sustainability Director Nina Morris emphasizes that the difficulties Penn faces with move–out are not unique. “If you go to any college campus, you will find the same story over and over,” she points out. In college towns like Durham, Boston, and New York, students—in a rush to vacate—leave behind thousands of dollars’ worth of usable furniture and household items on the sidewalks for local residents to claim.

While Penn isn’t the only institution faulted for move–out waste, Filkin admits it became clear that the University needed to “do a better job.” Before Penn implemented off–campus programs, he says University City District received dozens of complaints following move–out. Penn was failing to fulfill a central tenet of its strategic framework—being an engaged neighbor by thoughtfully managing resources and responsibly stewarding community members.

The path to a solution began with “learning from and listening to … neighbors, property managers, and students.” Penn’s move–out team recognized the need to address the challenges students face as they leave campus, from limited time to lack of transportation, while also tackling the “specific challenges of being an urban institution.”

To achieve this, the team spoke with folks at Penn who had experience “doing incredible work in the community to divert materials in a positive manner.” They also partnered with the Spruce Hill Community Association to gather input from local residents on what they hoped to see from Penn. This feedback helped the University identify two key priorities: residents wanted usable items to remain within the local community, and they emphasized the need for prompt collection of street materials to prevent litter. As a result, Penn’s off–campus move out efforts have focused heavily on curbside collection for both trash and donations going forward.

For community partners like the Philadelphia Furniture Bank and Rego, Morris says that the items students donate are often the “right size for the kinds of apartments they’re trying to furnish for people exiting homelessness or other serious situations.” Penn and UCD also work with the City of Philadelphia to increase the number of trash collections around campus from once a week to twice a week.

On campus, Dining Facilities and Project Manager Shennell Tyndell says that the University expands operations to “help manage move out,” including waste and foot traffic. Whether that be adding housekeeping staff or designating bulk trash locations, Penn is well aware that mid–May poses logistical difficulties. As a result, the University has developed “extensions” to the on–campus move–out program throughout the years, Tyndell notes, including partnerships with the Netter Center to give larger, more expensive items to high school students from the West Philly area who are going to college in the fall.

Penn increased the radius for donation pick–ups one city block at a time. Soon, the grievances from local residents about littered streets and negligent students dwindled. Last year, UCD received just two complaints. On the ground, the changes are visible, as sidewalks are no longer piled high with used furniture and bags of garbage spilling out into the street. It’s been a few years since Filkin has heard the term “Penn Christmas,” and he takes it as a sign that things are “moving in the right direction.”

Looking ahead, Morris hopes the University can find a solution for mattresses—an item often discarded by students with no sustainable option for repurposing. She also acknowledges that better communication and outreach to students earlier in the year could help “bake in the expectations for living off campus.” For students living on campus, Tyndell hopes Penn can partner with an organization that accepts food donations—items that students try to give away but that PennMOVES does not currently take. She adds that student groups and community–engaged volunteers often bring creative ideas and that such collaborations could open the door to new solutions.

“I hope it’s clear how many people are working together to make this better. I think that’s a beautiful thing, especially considering the way this was before was a result of people not coming together and figuring things out right,” Morris says. “This wasn’t one person’s problem. This was a community problem. I think seeing how many people have come together to solve this issue is just a great sign that our community is moving in the right direction.”

The chaos of Penn’s move–out season has declined with the implementation of donation and waste management initiatives. Staff members have worked to expand donation pickup zones, increase coordination with city services, and create partnerships with community groups to ensure thousands of pounds of discarded items stay local and useful. They are also listening more—to students, neighbors, and those working to address housing insecurity and sustainability in the area. “Penn Christmas” is no longer the phenomenon it used to be, and it’s one sign that the University is beginning to clean up its mess—not just on the streets, but in the relationships that define its role in West Philadelphia.

Even with the progress that’s been made, some holiday traditions have carried on—albeit on a smaller scale—and adapted to the changes Penn has made. By the end of move–out, the donation sites are overwhelmed, according to PennMOVES volunteer Grace Dong (C ’26). The overflow forces many students to leave items outside the designated bins, and although staff are instructed not to let local residents take things, people do so anyway, she says. It’s clear that no matter how many programs are in place, the underlying cycle will likely continue. Each fall, dorm rooms will fill with new rugs, mini–fridges, and trendy decor; each spring, those items will hastily find their way into a pile labeled “trash/donate.” The churn of college consumerism (buy, discard, repeat x4) is hardwired into the rhythm of campus life.

By the High Rises, a couple loads a desk lamp and crate of barely used toiletries from outside the donation bin into the trunk of their car. On Walnut, Jaden chats with an older woman as she sorts through a pile of books and clothes left in boxes on the sidewalk between Gutmann and Du Bois. The old adage still proves true—what students leave behind as trash, others claim as treasure.