Earlier this month, a friend told me he felt he needed me to accompany him to a hip–hop club event. I love hip–hop, but I am certainly not as well–versed as he is. Nevertheless, he told me that he didn’t feel comfortable entering the space on his own because he felt that he shouldn’t enter a Black space as a non–Black person. He felt that entering the space of a culture he enjoyed would be an intrusion, even though he was genuinely appreciating the music that he loved.

His hesitation captured something I’ve been thinking about for a long time—the belief that culture, especially within the realm of rap music, belongs only to the people who originate it. Black Americans have been the backbone of our country’s history, especially in music—yet the oppression that shapes Black art often is used to justify keeping that art exclusive. Rap music in particular is sometimes treated as so essentially “Black” that white participation feels out of place or even inappropriate.

But when Black music becomes mainstream, its audience inevitably becomes whiter, simply because the American mainstream is demographically white. What we often overlook is that changes in an artist’s fanbase don’t make the art itself any less authentic or less true to the artist. Instead, going mainstream actually benefits both the artist and their culture. There needs to be a shift in how we think about Black music and culture in general—from an exclusive to an inclusive view of Black art.

Playboi Carti is the perfect case study for this conversation because his entire career shows that Black art does not lose authenticity when its audience changes. Carti was born into the Atlanta sound, and most of the artists he’s brought into his record label Opium share those same roots. Opium emerged from the rage rap sound associated with the city—a genre that Carti himself helped pioneer. Under Carti’s guidance, the Atlanta sound evolved from ordinary trap music (think Future, Young Thug, Gucci Mane) into a darker, more sinister aesthetic with a chaotic, metallic sound. Regardless of the state of the genre he influenced, Carti has always remained himself, preserving his artistic identity and evolving on his own terms.

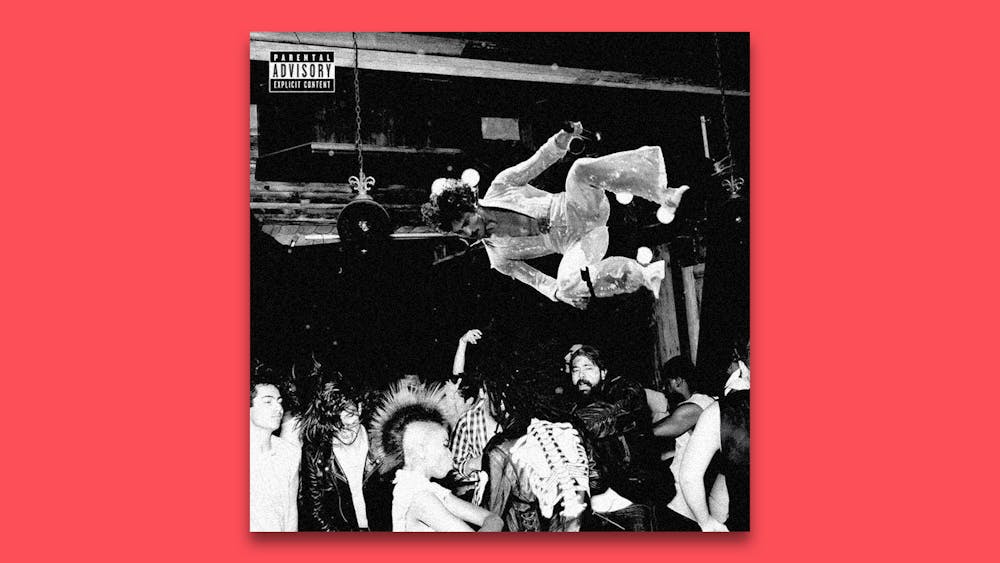

Opium is technically just a record label, but it functions more like a cultural movement. Under Carti, Opium has pulled Atlanta’s underground sound into the mainstream and built an entire aesthetic around black clothing, loud music, piercings up the wazoo, drug abuse, and just general alt–ness. Since Carti founded Opium, it’s rampaged onto the global stage while remaining unmuffled and unchanged, just like punk rock so many decades before it.

The similarities between Opium and the punk rock community of the late 70s are no coincidence. Carti himself said he drew inspiration from punk icons like Sid Vicious and publications like Slash Magazine for his sound and aesthetic. and that energy carried over into his most recent album, the concisely–titled MUSIC. When asked about Whole Lotta Red—his second studio album—in MARVIN magazine, he described himself as “just punk monk, bro. Punk. Monk. We can always go back to the gahdamn boom, boom, boom, but n****s had to evolve.” “Punk Monk” is the title of a song off of Whole Lotta Red, but it’s also a reference to who Carti is as an artist. He’s constantly being reborn into something new, something better, and something not necessarily in line with popular culture. In that sense, Carti is still counterculture in the hip–hop community, even as he's moved from being dismissed by most major rap critics as “mumble rap” to being praised as “hypnotic,” “infectious,” and “era–defining.” Carti is constantly evolving independently from outside influences, even at the cost of some initial criticism by his fans (especially on WLR). He stays authentic but not static, a Black Buddha pursuing the rebirth and perfection of the self.

Opium’s rise has followed a similar trajectory to the punk rock that Whole Lotta Red drew its imagery from. They both originally gained momentum for being different, but then were criticized once their fanbases became broader. When the counterculture became successful and popular, people who judge authenticity based on the audience rather than the art decide that the work is no longer authentic. This gatekeeping collapses authenticity into audience demographics rather than artistic intent, which is exactly what we shouldn’t do.

This tension was visible at Carti’s recent concert at the Xfinity Mobile Arena. Hundreds of thousands of tickets were purchased, and the concert was entirely sold out. Carti’s beloved mosh tickets were the priciest, going for more than $300. I personally couldn't afford Mosh tickets, but I nonetheless managed to get great seats. And from those seats, I noticed something very odd. There was a very weird feeling of racial segregation between the seats. The mosh was gentrified. Everyone was wearing black, but the crowd was unmistakably white. Carti’s popularity pushed tickets prices upwards and pushed the less privileged—his original audience—further away from the stage.

So, can we say that going mainstream is a bad thing? Is art exclusive to those who understand the struggle?

In a rare moment of clarity, Carti addressed his fans at the concert: “Each and every one of y’all … I know y’all are going through something. I see each and every one of y’all, I care for each and every one of y’all. Without y’all, I wouldn’t be here … I wouldn’t be here. I love y’all.”

Carti himself doesn’t seem to view his diverse crowd as offensive—and he speaks the truth. He wouldn’t have ever been able to sell out arenas the way he has on this tour if he had never become mainstream. He would never be able to “buy his mama a house of that mumbling shit” or create the Opium label without the support of people who didn’t directly share his struggle. By commodifying his personal culture, he directly profits from his pain. It’s unreasonable to say that non–Black fans are doing a disservice to Black people by actively and directly benefiting a Black man.

Furthermore, exposure matters. While Carti’s music might not directly solve or address systemic problems, continual exposure to Black voices and faces by non–Black consumers can make Black voices and faces more familiar, thereby reducing our culture's implicit biases. If Carti were to remain underground and his listeners were mainly Black, his culture and voice would not be available to a larger audience who might benefit from diversifying their perspectives and worldviews.

There is a point to be made about appropriation, and these arguments stem from a genuine and legitimate concern. There is a long history in the United States of non–Black people imitating and mocking Black people and culture in minstrel shows and things of the sort, portraying a caricatured image of Blackness that has done nothing but harm Black Americans. But the key difference to be drawn here is that most of the mainstream non–Black audience is genuinely consuming the art and culture instead of disingenuously mocking it. There’s a firm line between those modes of engagements, and it shouldn’t be crossed.

As long as it’s genuine appreciation, and as long as the artist stays true to themselves like Carti has time and time again, there’s no reason we should judge the art by its audience. In fact, through profit and exposure, a diverse range of people enjoying and participating in a culture that’s not theirs is good for both the artist and the larger community.

Culture isn’t some arbitrary property of a group; it’s a personal experience owned by people. Art comes from pain, yes, but making culture exclusionary monopolizes that pain, keeps the artist from fully blooming into their true self, and pigeonholes art.