Adrian Franco | 34st MagazineI really wanted to be a go–go dancer,” says Jennifer Jenkins to a crowd of customers waiting at her feet. It is a Saturday afternoon and the Rosin Box, a diminutive danceware shop on 20th and Sansom streets, is packed with long–legged ballerinas and their eager parents. Jenkins, whose own parents founded the shop in March 1977, is standing on a wooden bench, rummaging through a stock of pointe shoes for Maya, a caramel–skinned dancer, fresh from a two–hour class.

Jenkins is determined to find the perfect pair. After a few minutes spent shoulder–deep in the recesses of the shop’s many–shelved walls, she presents a pair of blush colored shoes to Maya. “Try these,” Jenkins says, but before dismounting, she does a little shimmy and explains, “My grandfather used to drive us down this block on Saturdays to see the go–go dancers. Sometimes we’d go around twice — and I thought he was doing it for me!”The Rosin Box — now in its third location — is squeezed on a block that houses thrift stores, a gay men’s lounge called the Sansom Street Gym and the Academy of Social Dance. But the shop is uniquely elegant. Displaying no sign, the Rosin Box is marked only by a short burgundy awning. Inside, the shop is dim, mostly relying on whatever sunlight filters through the leaded glass of the streetside bay window.

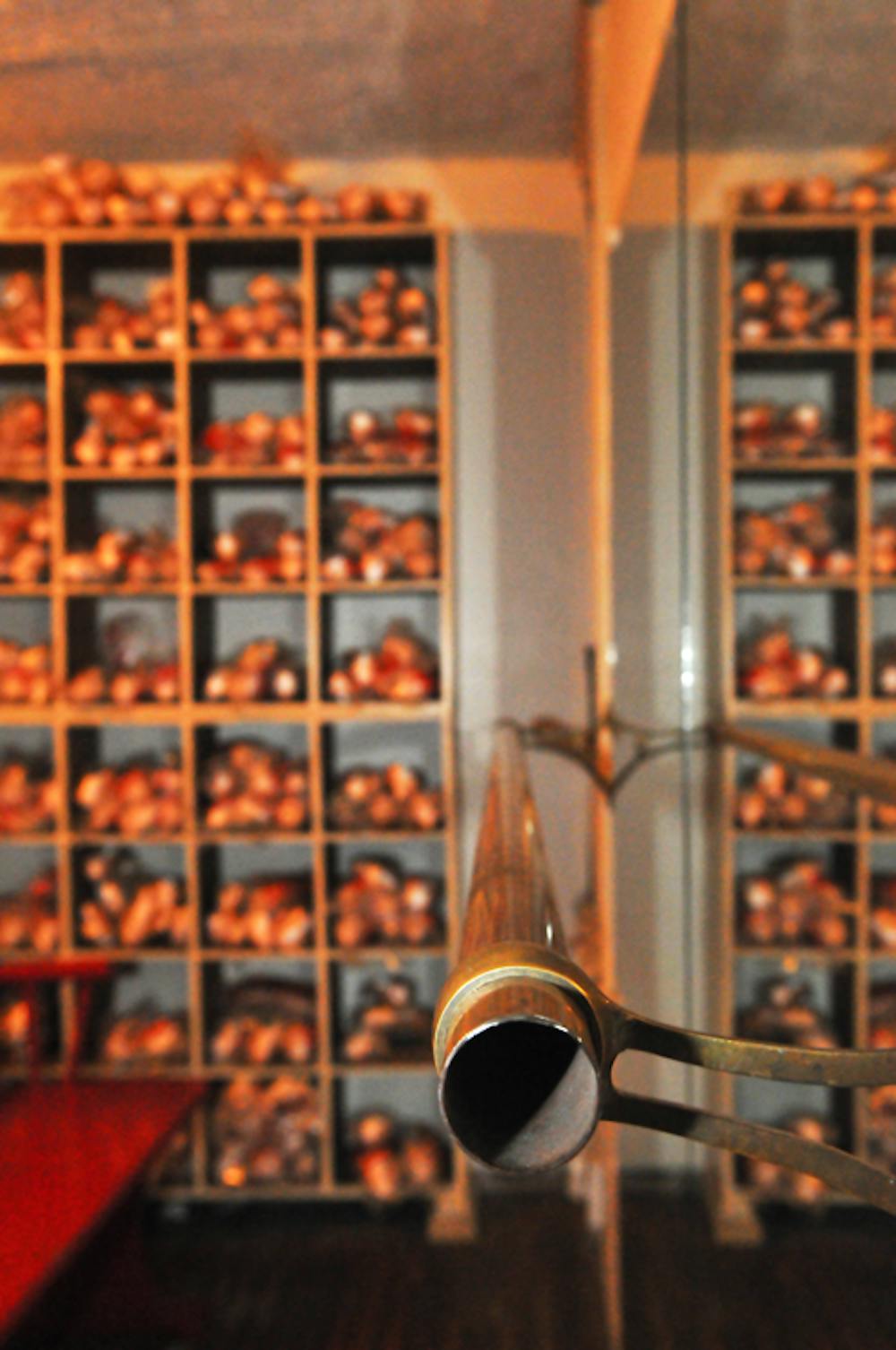

Adrian Franco | 34st MagazineThe space — what little of it there is — is decorated minimally. Black benches sit back–to–back, the farthest one facing a full–wall mirror on which a ballet barre is mounted. The sides of the shop are lined with bureaus which the Jenkins’ have painted a deep, romantic red. In every remaining inch of the Rosin Box, delicate–looking pointe shoes are stuffed one upon the other, seemingly overflowing from the crevices. “When people come in they say that [the shop] looks like something out of Harry Potter and we should be giving out wands instead of fitting pointe shoes,” says Jennifer.

When Angela and David Jenkins opened the Rosin Box more than 30 years ago, Jennifer and her brother Leonard were still dancing ballet. The shop was their mother’s brainchild; their father, who was then working as a sales representative for Good Humor and Abbott Dairies, supported it. Right away, Jennifer and Leonard began putting hours in when they could, balancing work, school and their blossoming dance careers. Still, they accredit the success of the shop to their mother. “She was here Monday through Saturday,” says Jennifer. “Sometimes we’d get two customers in all day. She just had this faith that it was going to work.”Named for a form of resin applied to the points of a dancer’s shoes to prevent slippage, the Rosin Box remains on its toes. All the same, the Jenkins’ have had to make a variety of changes in their inventory as danceware has ebbed and flowed between a mainstream fashion and a niche market. The shop has reduced its supply of garments to a bare minimum, but its clientele remains extensive; the Jenkins’ credibility as pointe–shoe fitters in the Philadelphia area and beyond has kept customers coming back for several generations.

Adrian Franco | 34st Magazine“My favorite part is the first pair of pointe shoes,” Jennifer explains. “The little girls come in to get their first pair of shoes, and after we give the dancer the proper fit, we take them over to the barre and they stand up on pointe for the very first time. Their faces just light up!” On Jennifer’s most cherished days, standing in the corner of the shop with a camera at the ready is a grandmother whose own feet had at one point received some of Jenkins’ attention. “It’s definitely geared toward families,” Jennifer said of the shop.

However, the boundaries dancers and their families will cross in order to seek the right fit are not purely generational. “We get people from North Carolina, from Baltimore; we get a lot of Princeton ballet students coming in here. Studio owners have said, ‘Okay, if you want a good fit you’ve got to go to the Rosin Box.’”Jennifer, beautifully tall and slim with her silvery–blonde hair pulled into a sophisticated bun, maintains an unwaveringly chipper air. Nevertheless, she and her brother explain that as magical as ballet — and for that matter, the Rosin Box — may appear, fitting pointe shoes is not so graceful, and neither is wearing them.

There are many brands of pointe shoes (Grishko, Capezio, Russian Pointe’s, Freed), all of which have distinct attributes that help them accommodate the shape of a dancer’s foot. Freed of London, whose shoes are considered to be some of the most upscale on the market, has twenty–two different makers, all of whose products vary in width and in the depth of their vamps. Still, to stand on one’s toes at such an angle is unnatural and can cause lasting damage that is as aesthetically unpleasing as it is painful. And while the Rosin Box exists to help dancers get as close to comfortable as they possibly can, there’s no escaping it: going up on pointe is a far cry from a foot massage.

More often than not, though, the dancers are not the ones with the biggest complaints. “Sometimes the parents get upset because I’ll talk directly to the kids,” says Leonard, “but it’s not like the parents are wearing the shoes.” Jennifer agrees that balancing the needs of dancers and the desires of their parents can be difficult. After all, the parents of ballerinas are like any other parents: they worry. And when it comes to ballet there is more than enough to worry about.

Adrian Franco | 34st MagazinePointe shoes are expensive, ranging from about 65 dollars a pair to over 100. As dancers get more advanced and begin spending more time on pointe, they wear through their shoes more quickly. When they reach the professional level — which in ballet occurs at around 17 or 18 years old — dancers are lucky if their shoes last a week. And as with many artists, a dancer’s pay is not by any means large. At 17 years old and immersed fully into a career on pointe, a dancer, or more likely her parents, will spend several thousand dollars per year solely on shoes.

In taking into account the monetary dedication that a dancer must make to her shoes, it is not irrational that after coming to the Rosin Box, parents expect their dancers to leave with the perfect fit that the Jenkins’ promise. But problems arise when parents are unable to distinguish between a good shoe and a good ballerina.“If you buy a bat at Modell’s and your kid still can’t hit the ball, do you bring the bat back to Modell’s and say ‘My kid still can’t hit the ball, what’s up with that?’” Leonard asked. Leonard, who is a little more reluctant to empathize with parental anxiety than his sister is, is skeptical of parents’ willingness to “blame the equipment.”

“As parents, I think we try to give too much to kids,” he says. “We want to make excuses for them when they fail, and instead of saying ‘It’s a good try but try harder,’ it’s like, ‘Oh well it’s not your fault honey, it’s the shoes.’” It sounds frustrating, but Leonard and Jennifer are unfailingly dedicated to their business and to its ability to better the lives of Philadelphia’s dancers. And though neither Jennifer’s nor Leonard’s children dance, the siblings have assumed concerns for their clients that are nothing short of parental.

“I literally lose sleep some nights over the fits that I think are going to come back,” admitted Leonard. “There are some feet that just don’t belong in pointe shoes. Humans don’t belong in pointe shoes. It’s a superhuman activity.” The Jenkins have noticed that their customers, who traditionally go up on pointe at around twelve or thirteen, are doing so now at increasingly younger ages. Currently, Leonard is trying to recruit somebody at the Children’s Hospital of Pennsylvania, where he works as a paramedic, to do some research on the long–term orthopedic affects of starting kids too early.

Leonard explains, “There’s this one theory of getting a cartilaginous, non–calcified little body and forming it into a ballet body. We see them at nine, which technically should be too young, but it seems to be more a trend than the exception now.”

But even more alarming than a lack of specified medical attention, is what Leonard relays next. “It is a very competitive business,” he says. “If one school won’t put [young dancers] on pointe and the parent is really pushing for it, then Ms. Susie down the street is gonna do it.”

Running a ballet school, like being a ballerina, isn’t cheap, and in this economy instructors can’t afford to lose their students. According to Leonard, the fiscal survival of a ballet program is due to whether or not it can maintain a base of what he calls “’Look Mom! I’m doing ballet’ kids.” These are students who want to dance, but do not intend to pursue professional careers. The more of these kids that ballet schools can get up on pointe, the more tuition payments they will receive, and the more resources they will have to cater to their more talented, pre–professional dancers. “Unfortunately,” says Leonard, “the real regulations on who can stick a shingle outside their little space and say ‘BALLET CLASSES HERE’” don’t exist.

Adrian Franco | 34st MagazineNonetheless, dancers and doctors alike attest that though wearing pointe shoes is uncomfortable, their effect on the body is not detrimental. So if the blisters heal, the bunions soften and the hips can be surgically replaced, what is it that is so notoriously unhealthy about becoming a ballerina? The psychological anguish.

Ballerinas need to be in impeccable and constant shape. Their art is one that is entirely aesthetic, requiring them — if they should decide to dance professionally — to maintain bodies that are exceptionally slim, if not emaciated. Moreover, a dancer’s focus need be, for all intents and purposes, inward. “You have to be a little narcissistic to be a dancer, because it’s all about you,” says Jennifer. “It’s all about your art form.”That a dancer’s ability to perceive reality will become so convoluted that like Nina Sayers, Natalie Portman’s character in Black Swan, she will drive herself to death in efforts to attain perfection is hyperbole, but it is not unimaginable. At 17 years old, most girls are concerned with whether or not they will be invited to the prom, not whether or not they will be selected for the leading role — or any role — in a major and career–making production. And for the most serious ballerinas, these predicaments and the decisions that need to be made to arrive at them begin long before adulthood.

Eliza Blutt is 13 years old. Her mother, Margo Blutt, danced at the height of her career as a principal for the New York City Ballet. Eliza is enrolled at an all–girls school in Manhattan, and after school and on the weekends she dances with the School of American Ballet, a feeder program for the NYCB. But if Eliza wants to continue dancing, at least at the rate she is going, she will need to make a major change in her life by the end of this year.

In order to enter into SAB’s Second Intermediate B2 level, Eliza will need to attend ballet class every day at 2:30 p.m., forcing her to withdraw from her academic school. If Eliza and her parents decide to make the switch, Eliza will most likely attend Manhattan’s Professional Children’s School, an institution whose mission statement declares that it aims “to teach young people to balance the demands of their professional, personal and academic lives.” “She’s making a career decision at 13 years old,” says Eliza’s mother.

And if this is not terrifying enough, in ballet, explains Jennifer, “there are no guarantees. Even if you’re talented, it is a very precarious direction to go in.” So why, then, if dance is so risky; if it has the potential to drive twirling little girls in fluffy pink tutus to madness and malnourishment, to push parents over the edge of obsession and to force children like Eliza to make decisions that might be reserved for those well into adulthood, why do they keep doing it? The answer, at least to Jennifer, is indisputably clear.

“They don’t have a choice. They love it. The alternative would be not dancing, which is not an alternative. It’s not really a sacrifice to them, the unknown, because they’d rather be dancing.”

So in the end it seems that to the dancers it is all worth it — the split toenails and the hammertoes, the missed school dances and the dates turned down — just to spend a part of their lives on the pointe.