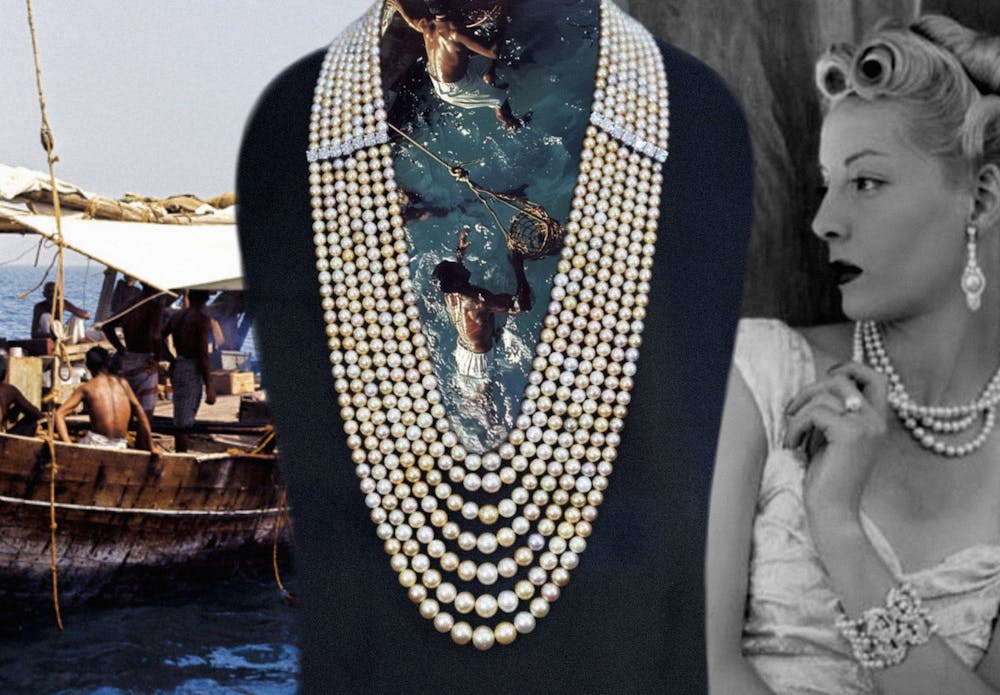

From the depths of a saltwater sea, gushing with freshwater springs, thousands of oysters are shucked in the hopes of yielding a perfect pearl. Once famed for its rare natural saltwater pearls, Bahrain—known as the “Land of a Million Palm Trees”—held a glittering place in the global pearl trade.

Pearls are everywhere. From Johannes Vermeer’s Girl with a Pearl Earring (1665) to Breakfast at Tiffany’s (1961), these fabulous gems have long been a symbol of status and heritage. Their glamor and intrigue, however, often overshadow their unique history.

The Kingdom of Bahrain is a country consisting of an archipelago of islands off the southeastern coast of the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. The name “Bahrain” means “two seas” in Arabic, a nod to the freshwater springs that bubble from underneath the saltwater seabeds. The country is known for its rich history and culture—spanning the ancient civilizations of Dilmun and Tylos, pearling traditions, the discovery of oil in the Gulf, and, more recently, its annual Formula 1 Grand Prix. It is home to around 1.5 million people, with a warm, welcoming culture.

The pearling industry in Bahrain traces back to as early as 3000 B.C., during the Dilmun civilization.

Dilmun was a famed trade center, and was mentioned often in Mesopotamian literature. One early text, Enki and Ninhursaga, describes it in glowing terms: “Pure is Dilmun land. Pure is Dilmun land. Virginal is Dilmun land. Virginal is Dilmun land. Pristine is Dilmun land… No eye diseases said there: ‘I am the eye disease.’ No headache said there: ‘I am the headache.’ No old woman belonging to it said there: ‘I am an old woman.’ No old man belonging to it said there: ‘I am an old man.’ ”

The Roman historian Pliny the Elder wrote that pearls from the Gulf were “the most perfect and exquisite pearls of all other[s].” In the first century A.D., Isidorus Characenus described the pearl diving process in Tylos (an ancient name for Bahrain): “The island of Tylos, was surrounded by bamboo rafts from which the natives dive in 20 fathoms of water and bring up bivalves.” Even Ptolemy mentioned the Tylos fisheries in his Geographia, mentioning the Thilouanoi (Bahrainis) and the city of Arados (believed to be modern day Muharraq).

Muharraq, the former center of Bahrain’s pearling industry, once served as the nation's capital, before being replaced by Manama at the start of the oil era in 1932. Bahrain was the first country in the Gulf to discover oil, kick–starting the oil industry in the region; oil was discovered in Saudi Arabia and Kuwait just a few years later. For young Bahrainis entering the workforce, jobs in the burgeoning oil industry were a safer alternative to pearl diving.

By 1950, a variety of factors—World War I, the 1929 stock market crash, and the introduction of pearl cultivation—caused the Bahraini pearling industry to fall, and efforts were refocused on the emerging oil industry. Many pearl merchants were still selling pearls that they had acquired in the 1930s until as late as 10 to 15 years ago. In his 1953 book on pearling, Léonard Rosenthal wrote that the pearl industry was directly impacted by the Great Depression. The Bank of France announced in 1930 that they would not grant pearl merchants their typical credit—that same day, the value of pearls fell by 85%.

Before then, pearls were Bahrain's most significant export. In 1877, three–quarters of Bahrain’s total exports were pearls, and around 1904–1905, Bahrain was the most significant hub for pearl trading in the Gulf, with 97.3% of the Gulf’s pearls being traded through the country.

Despite the decline of the natural pearling industry, Bahrain is the only country in the world to ban Pearl Cultivation. Danat, the Bahrain Institute for Pearls and Gemstones, was established in 2017, evolving from its predecessor, the Pearl and Gem Testing Laboratory of Bahrain. Gemologists there can differentiate between natural and cultivated pearls through the use of X–ray imaging.

Bahrain maintains its rich pearling heritage. Despite the decline in the pearling industry, the history of Bahraini is a point of great national pride, and efforts have been made for a revival of the national pearling culture, including the “Muharraq Nights” Festival, and the introduction of pearl diving licenses for both individuals and professional divers to harvest natural pearls.

Once the center of the global pearl trade, Bahrain exported the finest natural pearls in the world. A favorite of Queen Elizabeth II, the Bahrain Pearl Drop Earrings are one of the most famous examples of Bahraini Pearls. The two pearls affixed to the set of earrings comes from a gift of seven natural Bahraini pearls given to Queen Elizabeth II in 1947 as a wedding present from the Hakim of Bahrain, Shaikh Salman bin Hamad Al Khalifa.

There are three categories of pearls: synthetic, cultivated, and natural. Typically, saltwater pearls are more valuable than freshwater pearls due to their lengthy production time. Additionally, all saltwater pearls are bead–nucleated, while freshwater pearls can be either bead or tissue-nucleated.

Today, Mikimoto—a luxury jewellery house known for the cultured pearls they’ve produced since 1893—is one of the biggest names in pearls, but natural Bahraini pearls were once some of the most coveted. The value of Bahraini pearls lies in their status as natural pearls and in their unique history on the island.

Mikimoto’s revolutionary pearl cultivation method caused a decline in the natural pearl industry in the Gulf. Despite the enduring value of natural pearls, their rarity poses an issue for jewellers. A single strand of natural pearls, all equal in size and quality, can take years to create, because finding pearls that match is no easy feat. As natural pearls are formed without human intervention, it is difficult to find perfectly round, high–luster natural pearls. Before cultured pearls rose in popularity, it was a string of 128 natural South Sea pearls that first got Cartier its New York flagship store on Fifth Avenue. Valued at around $1 million, the necklace was traded for the home of Morton Plant—whose wife, Maisie Plant, fell in love with the necklace.

Finding pearls was not only difficult, but also strenuous and dangerous. Pearl divers could spend hours under the blistering sun, plunging into the sea, uncertain if the oysters they retrieved would bear any pearls. Men would spend months out at sea upon wooden dhows, diving during the day and resting together in the evenings. Breakfasts consisted of dates, tea, and coffee; dinners were freshly caught fish with rice and tea.

To boost morale, crew members often sang songs, Fijiri, together (listen to the album Bahrain: Fidjeri: Songs of the Pearl Divers to hear them firsthand). This involved singing, hand clapping, and playing music on drums and pottery jars. These songs live on through Bahrain’s oral traditions, passed down the generations.

The dives themselves were intense. Divers clipped their noses shut with animal bone, wore leather finger gloves, and tied stones around their ankles to sink more easily to the seabed. They carried bags around their necks to collect oysters. Injuries such as burst eardrums were common, alongside jellyfish stings, shark attacks, and decompression sickness.

Pearling is rooted in Bahrain’s heritage. In 2012, UNESCO designated Bahrain’s Pearling Path a cultural heritage site. Today, it’s a popular attraction in December for the “Muharraq Nights” Festival. Spanning approximately 2.2 miles, the path begins at Qal’at (Fort) Bu Maher—a fort which once played an important role in protecting Muharraq and its pearling basin. The other end of the path leads to Siyadi Majlis, a building that once hosted pearl merchants from Europe and Asia, and now houses a pearl museum displaying traditional pearl–diving tools alongside jewelry crafted with the finest Bahraini pearls. I visited last December, and I marveled at the beautiful interior, with the newly renovated walls of the main exhibition made of silver–foiled plaster, with a mother–of–pearl–like sheen. I pushed myself up as close to the display cases as I could without touching the glass, admiring the array of jewelry: a diamond encrusted palm tree with a single pearl crowning its fronds, a five–strand pearl necklace, and earrings with delicately hanging strings of pearls.

The museum has “an agreement with Cartier to have a rotating exhibition each year.” Cartier writes that “A long–term loan from Cartier enriches the Pearl Museum in Muharraq, part of Bahrain’s UNESCO–listed Pearling Path. This unique cultural landscape tells over a thousand years of pearling history.”

The palm tree brooch was designed by Cartier. Jacques Cartier first visited Bahrain in 1912, searching for the highest–quality pearls for the French luxury jewelry house. Francesca Cartier Brickell—whose great–great–great grandfather, Louis–François Cartier founded the brand—writes, “Perfect #naturalpearls were almost impossible to find, but the best, the Cartiers believed, came from the Gulf.”

The Cartiers wanted to purchase pearls directly from the source, bypassing middlemen who might inflate prices or sell lower–quality gems. So Jacques Cartier traveled to the Middle East to establish direct relationships with pearl merchants. By then, the French Rosenthals had already established a relationship with pearl merchants in Bahrain, and the Cartiers didn’t want to be left out.

The Rosenthals had first traveled to the Middle East to buy pearls in 1905, purchasing around $1 million (in today’s currency) worth of pearls—and double that in 1906. In 1907, while other jewelers purchased less due to financial issues, the Rosenthals forged ahead. They shipped millions of francs to the Gulf, and had 50 donkeys pull them in a procession to Victor Rosenthal’s home, hoping to impress the pearl merchants. Léonard Rosenthal aimed to control the pearl market, much like De Beers did with diamonds, by purchasing as many of the world’s finest pearls as possible. But like Bahrain’s pearling economy, the Rosenthals’ business was adversely affected by Mikimoto’s innovations in pearl cultivation. Leonard Rosenthal objected to the advertising of the manufactured gems as “pearls,” and sued Mikimoto. A 1921 article in a London newspaper read, “cultured pearls sold by a certain Japanese merchant are only imitations of real pearls and it is misleading to label them as pearls when they are not.” After numerous lawsuits, Mikimoto was granted the right to label his pearls as such, but had to call them “cultured pearls” to distinguish them from “natural pearls.”

Jacques Cartier documented his search for pearls in his diaries, meeting with Bahraini pearl merchants and spending time aboard pearl–diving dhows to learn the process firsthand. He visited Bahrain many times between 1810 and 1923, writing in detail about pearl diving techniques: wax inserted in the ears, stirrups and baskets weighed down with stones, and ropes tied to feet. In one entry, he described a morning in which 200 shells had been collected without finding a single pearl in them. For the Cartiers, it was essential that customers knew that their pearls came directly from the source. Though the Cartiers bought pearls from Bahrain, they hadn’t been able to build the same relationship with Bahraini merchants as the Rosenthals.

In November of 2022, Francesca Brickell Cartier visited Bahrain, retracing the steps of her great grandfather Jacques. She participated in the “Danat” pavilion of the Jewellery Arabia Exhibition, tried to pearl dive, and recreated a photo he had taken in Bahrain alongside the descendants of the other men in the photograph.

Today, pearls may conjure images of grandmotherly elegance—strings of pearls paired with twinsets and brooches—but they’re in the midst of a resurgence. The 2025 Van Cleef & Arpels Holiday Pendant, for example, is a pink mother–of–pearl pendant, set in rose gold, with a single central diamond—a hallmark of the brand’s holiday pendants since 2005 (with exceptions for 2006, when none were released, and 2008’s butterfly shaped holiday pendant). Pearls are also the perfect summer accessory, with strings of small freshwater pearls commonly adorning the necks of teenagers and adults alike. Pearls aren’t going anywhere, but it’s worth remembering the cultures and traditions that came long before modern pearl cultivation and trade.

Mikimoto is a household name among jewelry enthusiasts, but many are unaware of Bahrain’s pearl legacy. Pearls formed a pillar upon which modern Bahraini society (and the luxury jewelry industry) was built, and their global impact should not be understated.

While pearls aren’t exclusive to Bahrain, or even the Gulf, it is important to preserve the country’s unique pearling history. It's important in fashion to acknowledge the influences of different cultures—why wouldn’t we afford the same diligence to our jewelry? We cannot forget the men who risked their lives for the iridescent gems, or the families they left behind. We must remember the women who supported each other at home, praying for the safe return of their husbands, brothers, and sons.

Pearl diving was never just a means to produce jewelry. It was the livelihood of a nation, and the source of community and traditions that are still deeply embedded in the culture of post–pearling Bahrain. It is the industry upon which Bahrain was built—before oil was ever found in the Gulf.

Bahrain’s pearling legacy still endures. The 18–karat gold Arabic name necklaces popular among Bahraini women—adorned with tiny pearls where the dots of their names fall—are more than just a fashion statement. They’re an act of remembrance, proof of a resilient heritage.

While it’s incredible that pearls are so much more accessible now than ever before, the labor, craftmanship, and danger behind them must not be forgotten. Pearls built nations. They built legacies. The global jewelry industry wouldn’t be what it is today without them.