“Fiona, I’ll leave now—I don’t want to take up too much of your time.”

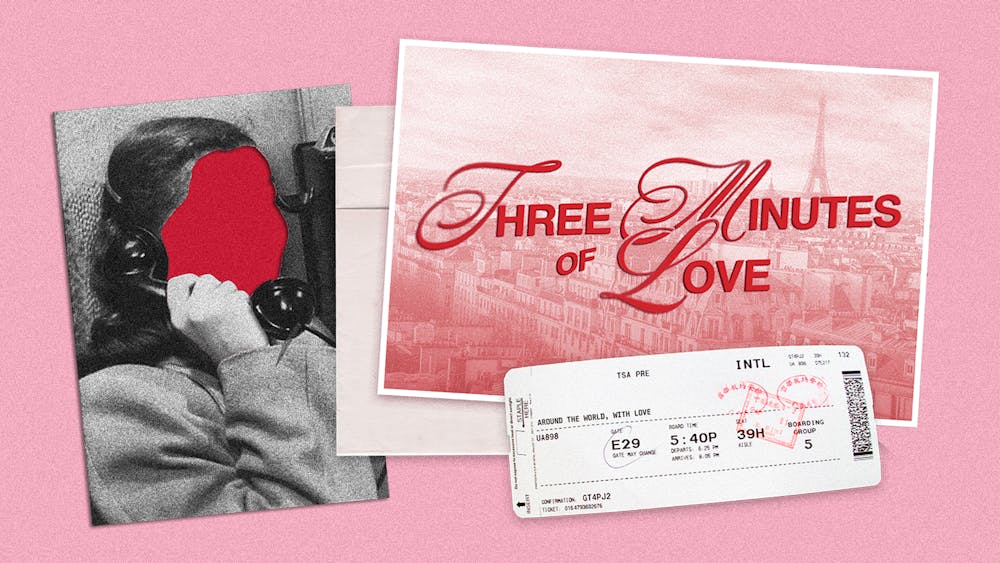

Whether I’m waiting between classes or sitting at home waiting for dinner to be ready, my grandmother ends every phone call the same way. These calls last barely three minutes. No matter how often I insist that she could never take up my time, she hurries to hang up, as if her love must be given in small, unobtrusive doses. And yet, in spite of previous worries of taking my time, like clockwork, she calls again the next day.

Dementia and the unyielding passage of time have reshaped the dynamics of my family in ways I am still struggling to find my place in. Not only has dementia taken pieces of my grandmother’s memory, it has altered her sense of self. Once defined by fearless independence and nonstop action, she now organizes her days with caution and repetition, haunted by the belief that her presence is a burden—even to the people who want nothing more than to spend time with her.

My grandmother was once unable to be restrained as she freely jetted around the world. One week she mailed me Olympics merchandise from South Africa. Another week it was a cat sweater from a boutique in France, tucked alongside a pencil topped with a miniature Eiffel Tower. Even when I visited her in her house in Syracuse, N.Y., she allowed no time for lethargy. Jet lag was irrelevant. My grandmother woke me at 7 a.m. to make breakfast, get our nails done, shop for clothes, run errands. Every hour was filled. I didn’t yet understand how empty Syracuse would feel without her momentum propelling it forward.

I once defined her life by motion and agency. Now, the only remnant of that motion reveals itself in how she walks.

At The Nottingham, the senior living community where she has resided for just a year, the only remnant of her former independence reveals itself in her pace. As she grips my arm to guide me to her daily 4:30 p.m. dinner, she marches swiftly through the halls, pulling me forward, impatient with the measured pace of assisted living. Even as her world narrowed, there is a trace of the urgency she once carried, as if her body remembers a tempo her surroundings no longer require.

I once knew my grandmother loved me because she used every tool at her disposal to engage me. Sometimes it was through interests she believed I should have, such as encouraging me to practice French by sending storybooks across the country to Los Angeles. Other times it was by nurturing the passions I discovered myself. When I became preoccupied with environmentalism in middle school, she mailed me books, forwarded articles daily, and recommended educational programs. I mistook these actions as spontaneous expressions of love, never considering the time and effort required behind them.

Now, that expression of love has dimmed. The energy that once lived behind the scenes of listening, researching, and planning has faded. My grandmother spends her days playing solitaire alone in her room, calling only the people she already trusts. When we talk, she repeatedly asks what I study, where I go to school, what day of the week it is, carefully affirming the answers as though anchoring herself to information that dementia has claimed. After the routine 4:30 p.m. dinner, she prepares for bed, ending her days early. Her world has shrunk—and with it, her willingness to claim time from others.

When I stayed with her in The Nottingham, she insisted I return from the gym by 7 p.m., afraid of the dangers in the secure halls occupied by senior living residents. The building that now contains her life feels dangerous to her in ways the world never did. When something goes awry—the heater breaking, the television remote becoming misplaced—her anxiety takes over as she retreats inward, becoming less willing to see family. This fear feels foreign against someone who once thrived on the necessity of navigating things beyond her control. Independence once meant movement, exposure, and risk. Now, independence is found in repetition, predictability, and early nights alone. What used to be confidence in the unknown has hardened into anxiety around the smallest disruptions.

I am afraid of the time we have left in this new reality. I can feel panic ripple through my family as we try to maximize every remaining moment. This winter, we flew from Syracuse to Los Angeles, then within 24 hours, boarded another plane to Taiwan to spend a precious few days with my aging grandmother on my mother’s side. Time has become something to chase as it slips away.

The time my grandmother once spent nurturing my interests has come to an end. Now, it is my responsibility to spend precious time simply sitting with her, waiting, and sometimes just breathing alongside her. We watch the news together in the afternoon, eat simple meals of bread and cheese (accompanied with a glass of wine), letting the quiet between us stretch without urgency. When we are physically apart, I am the one to constantly send information on what I am learning, books I think she’ll find interesting, and photos and videos on all the exciting adventures I embark on.

Loving someone whose identity has changed so drastically requires learning a new language of love. It also asks me to change, to release who my grandmother once was and who I once was with her. Love and time, even as they grow quieter, still ask to be honored—in patience, presence, and three uninterrupted minutes at a time.