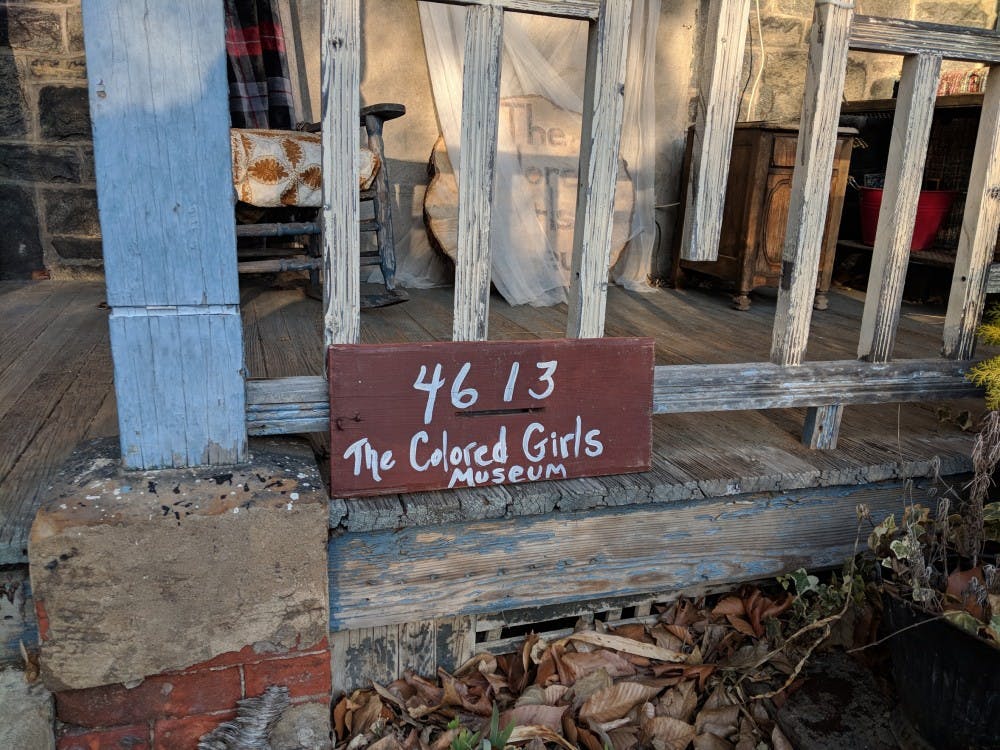

Children outside leap playfully, it’s warmer than usual, and cloudier. I can feel the ambiance changing from comfort to a sort of suspense as I see a small sign with the title “The Colored Girls Museum.” I realize, that despite brief research, I don’t know what to expect.

Vashti Dubois opens the doors of her home, which doubles as a museum. She greets me with a smile, and welcomes me inside. Immediately, I feel at home. Maybe it’s the warmth, maybe it’s the faint smell of tobacco, maybe it’s the heavy presence of the art surrounding me and Vashti’s casual ease around it, as if she’s used to living with all of these entities. I’m prompted to sit down in what I would later discover is the reception area.

After a series of brief introductions, she tells me about how the idea was essentially inspired by Urgent Care, or the lack thereof in disadvantaged communities.

“[Our] Artists think of every room as if we were in an Urgent Care facility designed by the Colored Girl herself. So if you were coming into our hospital system: ‘What would our reception area look like? What would our drugstore look like? What would our triage look like?’" Vashti tells me.

"We really think about [the art] in terms of what’s their curative power. It’s more than a contemporary art space, we think about how the work functions in different ways,” she continued.

This purpose is what provides the essential narrative spine to the story that Vashti’s museum tells. Every room has, not only a curative purpose, but a symbolic one as well.

Vashti discusses the reception area. “It can be such an upsetting thing when you realize you’re not welcome. You try to figure out how to get yourself into a place that you think you’re already in.”

I peer into the “reception desk,” a cradle of herbs with curative properties. Inside is a quote: “we are the ones you’ve been waiting for.” Vashti explains that you have to welcome yourself into the space if you’re not welcome. Immediately, I think about Penn’s community. I think about how as a First–Genration/ Low–Income student, Penn did a decent job at admitting me, along with others in my position, but once we’re here, not much is done to help with the process of integration.

Vashti proceeds by showing me sculptures of girls, vessels. They’re tributes to the girls who were killed in the 16th street Baptist church bombing in Birmingham in 1964. “Our mission is Protection, Praise, and Grace. We hold these girls in reverence, and then symbolically all girls of color.”

The tour of a very holistic approach to wellbeing continues, and the smell changes from tobacco to a musky sandalwood. A beautiful tent of old, torn bed sheets offers privacy and introspection in the triage room. “The physical is always related to emotional, the spiritual. It’s a tent for the colored girl, where she can sit in a basket (made by African weaving technique), with letters dangling from the top which contain whispers of dreams, thoughts, and hopes.

Next we enter the exam room. A mural (“Riverbed”) by Intisar Hamilton adorns the walls and ceiling. Blues and oranges in swirls created by a Self–taught artist bring to mind feelings of nature, of divinity. The narrative proceeds, the experience entails what it’s like to be examined as a woman of color, of the importance of self examination.

I ask Vashti, a mother and a widow, about how her children felt about her project. “They were just really happy that I had something to focus on. While I was figuring out what next person I would be, I was on this thing, and that’s what I was doing. They were just glad that I had somewhere to invest my artistic energy into, because, my husband was my art partner. So then there was the question: will she continue to create art now that he’s gone? And if she doesn’t, who’s she gonna be?”

She recalls fondly, “We usually worked on big scale projects together. We also did some things in NYC. I was working on a one–man show for him because he was a wedding singer and his stories were hilarious. So we did stuff like that, it was a funny household.”

I inquire, “Where do you see it going?”

“In terms of the evolution of the Colored Girls Museum, I’m gonna use the words university and campus. I see it as part of a bigger system, I see it as the necessity of having a space that really celebrates the ordinary extraordinary colored girls because there are no spaces like that which are really for and by and about us. I see this as part of a bigger educational system, a bigger think tank, residency, so that you can come, stay, study.”

So what kind of people do you usually get visiting? “Well, our target audience is the Colored Girl. But it’s not for the Colored Girl only, it’s for anyone who’s ready for a consciousness revolution."

The tour continues and we enter what came to be my absolute favorite room. It is a tribute to the washer woman, the only permanent exhibit in TCGM.

“We think of the washer woman as foundational to the story of the black community.” Vashti explains, “So, after emancipation, black men couldn’t get work. People didn’t want to hire them because they had been getting all that labor before for free, so rather than pay them they would arrest them as vagrants. The only people that would get work were the women, so we went back to doing the work that we had been doing during enslavement: taking care of children and doing laundry. And this is very, very, very, hard work. But this hard work built churches, it built houses, it kept people from getting lynched, it put food on the table, it is foundational. We would not be here but for that work.” (This is where my eyes swell to the brim with tears.)

I think back to my own history as a Latina. I think about the centuries of pain and sacrifice that only women can know. I think about my grandmother. I think about my mother. I think about the lengths that she’s gone to ensure that I grow strong, resilient, and unapologetic. I think about all the mothers of the girls of color that I know, and how difficult it must be to bore a daughter knowing well the complications that skin and stereotype entail.

Vashti hands me an ancient iron. It is heavy, heavy with history. For the purpose of exhibit: this is the historic records room.

Vashti describes the impact of her museum via a phrase that she hears from her visitors: “People say, I didn’t know I needed such a place. That is principally what we hear.”

Meanwhile, for her “it’s been very healing. Colored girls, we’re all walking talking museums. We’re full of the arts and artefacts of our lives.”

We enter the penultimate room, the apothecary. It is adorned with hair pieces, mostly comedic ones such as hair tucked in a frame titled “Now you can touch my hair” and a chair upholstered with hair. Despite the humorous undertones, this room speaks to the very intimate experience between a colored girl and her hair, a theme of constant conversation and struggle. A centerpiece of identity, in a tangled and tangible form.

The final room is a sort of outpatient facility, brightly adorned. Vick’s VapoRub stands out, flashbacks to my childhood ensue. Feeling renewed, Vashti offers me a mandarin.

“Art is not about pretty shit on the wall, it’s about creating a story, having an intention, and understanding how it can very powerfully move a conversation and change a circumstance. And that’s why my favorite point in any theatre is when the lights go down, because at that moment you’re joined in a very intimate experience with a bunch of strangers: where else are you gonna go and let people turn off the goddamn lights, right?” Vashti jokes, “And you’re gonna sit there. Where else are you gonna do that? And then the lights come up and you’re in somebody’s story.”

We exit, the curtains drop.