“I think you’re the first one, ever, at Penn, to ask me about my experience here as a person with a disability,” says Engineering senior Tanner Haldeman. He attempts to recall another time he was asked about his experiences and not just surface–level questions about the scooter he uses to navigate campus—questions which become grating over time. During three and–a–half years at Penn, Tanner’s experience as a student with a physical disability stemming from a neuromuscular disorder went largely “ignored.”

“I think you’re the first one, ever, at Penn, to ask me about my experience here as a person with a disability,” says Engineering senior Tanner Haldeman. He attempts to recall another time he was asked about his experiences and not just surface–level questions about the scooter he uses to navigate campus—questions which become grating over time. During three and–a–half years at Penn, Tanner’s experience as a student with a physical disability stemming from a neuromuscular disorder went largely “ignored.”

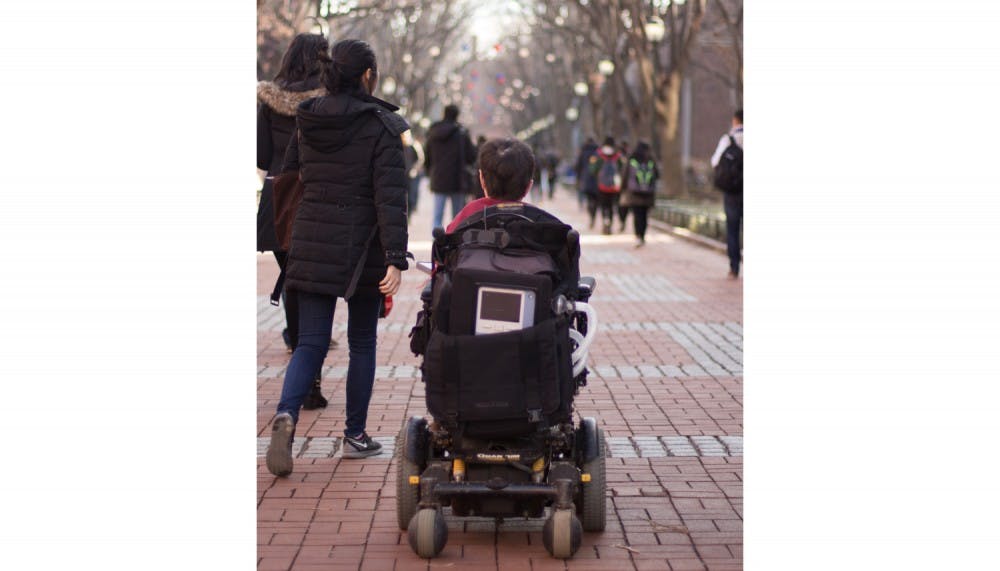

Few, if any, ever asked the important questions. “A lot of people,” Tanner says, “especially just walking down Locust Walk, will just glare or look at my scooter and then look at me…No, I’m not a scooter with no person on it.” It’s possible many won’t ever engage with his self–proclaimed Midwestern charm, but rather a particular vision of him. For some students on Penn’s campus, the conspicuousness of a physical disability, no matter how visible it may be to others, is juxtaposed with the invisible challenges they face, large or small.

Whether it be everyday problems like malfunctioning automated doors or more systemic issues such as the inaccessibility of off–campus life, students dealing with impaired mobility due to physical disabilities or chronic medical conditions must put in extra work to navigate a world filled with obstacles invisible to able–bodied students. As Wharton freshman Julianne Martin, who has been paralyzed from birth and uses a wheelchair, explains, “What I’ve observed is that with physical disabilities the problem is easy to see, but tough to solve.”

Tackling this reality is no doubt difficult, and as Dr. Myrna Cohen, Executive Director of the Weingarten Center where Student Disability Services (SDS) is located, explains, “It’s sort of the eyes of the entire university that have to be sensitive to the needs of the student population.” But Tanner’s observations pose important questions: where are Penn’s eyes? Are they looking at a wheelchair or a scooter, or are they looking at the people who use them?

Accessibility and Accommodations

By many accounts, Penn serves students with physical disabilities well; Julianne, as a freshman not too far removed from her memories of the college search, described Penn as better than most of the colleges she toured in terms of accessibility.

While college senior Luke Hoban, who has a congenital form of muscular dystrophy, notes that student experiences with accommodations and accessibility vary, he says he is “pretty happy” with Penn’s ability to meet his needs around note–takers, classroom laptop use, testing accommodations, as well as accessible living situations and home health aides.

Behind much of the accommodations for students with physical disabilities lies Student Disability Services, which is the main point of support for students with disabilities at Penn, physical or not. Each year SDS supports approximately 30 students across undergraduate, graduate, and professional programs with mobility impairments who are not able to “get around in conventional ways” as Director of SDS Dr. Susan Shapiro explains. This number includes both students with physical disabilities as well as chronic health conditions. Many students reach out during the college search, as Julianne did, or self–identify with SDS over the summer before the start of their time at Penn.

Generally speaking, SDS, among other services, helps assure students accessible housing and testing locations, as well as appropriate time extensions for exams. Dr. Shapiro explains that SDS’s support functions are also highly individualized, often working with “students with more significant needs” right down to the particulars of reworking a kitchen setup in college housing for a student who couldn’t turn the knobs on the stove. In Luke’s case, his room in Harrison is outfitted with a special clicker given his inability to use a standard room key. SDS’s work, though, is almost never done; Dr. Shapiro notes the constant construction on Penn’s campus, the possibility of snow, and the sheer size of campus as just a few of the challenges in providing as accessible of a campus as possible for the student body.

You can sense the appreciation for SDS in Julianne’s voice when she humorously, but sincerely calls the disability services team “bae,” praising their helpfulness and receptiveness to student needs. In fact, SDS helped broker a conversation between a current student and Julianne to discuss life with a physical disability at Penn when she was still in high school.

You can sense the appreciation for SDS in Julianne’s voice when she humorously, but sincerely calls the disability services team “bae,” praising their helpfulness and receptiveness to student needs. In fact, SDS helped broker a conversation between a current student and Julianne to discuss life with a physical disability at Penn when she was still in high school.

Dr. Shapiro explains that SDS provides access for all academic and university–sponsored programs, even if it means relocating an event or installing handicap accessible entrances to buildings. But despite SDS’s efforts, there remain accessibility issues on campus.

Tanner recalls a frustrating attempt to get into an academic building for an economics review session; heading to the back of the building where Google told him there would be an accessible entrance, he was greeted by a locked door. Using a nearby help button he was connected to the Penn police who told him he had the wrong number. He then called a help number on a nearby sign, which appeared to be disconnected, leaving Tanner unable to attend his review session. He was already late due to the difficulty of accessing the building in the first place. “I think that it’s a pretty fundamental right that people should be able to go into buildings,” he says. In another instance, Tanner reported a maintenance issue to SDS but was passed off to the building manager. “SDS isn’t just isn’t a lookup service for who’s in charge of what building,” he says. “Like I can find that on Google.”

Julianne, while noting the large amount of ramps on campus, points out that "from a female perspective," the location of the ramps can be worrisome. “They’re all in back alleys or around the side of buildings,” she says. “I’m just like, there are no cameras, there is absolutely nothing, the lighting is horrible.” Moreover, Julianne points out that accessible entrances and ramps are often hidden or obscured, forcing her to go “under the river and through the woods” to get inside a building, while stairs always lead directly to an entrance.

While Dr. Cohen notes that accessibility of campus buildings is likely in the 90th percentile and that organizations like the Philomathean society will often move events from the wheelchair inaccessible Philomathean Hall upon request—one of the few inaccessible locations on campus—problems still arise. These are all inherent issues with, as Luke explains, “being disabled in a world that isn’t built for it.”

Chartering a Social Life

While Wharton senior Mike Brodsky’s neuromuscular condition initially made it more challenging for him to meet frats—many are not wheelchair accessible and are not covered under the Americans with Disabilities Act, as they are treated as private residences despite being on Penn property—he eventually found his home in the off–campus fraternity Theos during his junior year. Mike wanted a “normal college experience,” and he feels that he’s found it just being one of the boys in Theos. As Mike acknowledges, his experience might be quite different from other students with physical disabilities when it comes to forming social lives.

While Wharton senior Mike Brodsky’s neuromuscular condition initially made it more challenging for him to meet frats—many are not wheelchair accessible and are not covered under the Americans with Disabilities Act, as they are treated as private residences despite being on Penn property—he eventually found his home in the off–campus fraternity Theos during his junior year. Mike wanted a “normal college experience,” and he feels that he’s found it just being one of the boys in Theos. As Mike acknowledges, his experience might be quite different from other students with physical disabilities when it comes to forming social lives.

Echoing some of Mike’s early challenges, Luke finds that social life at Penn can be frustrating due to how inaccessible many off–campus buildings at Penn are, “It’s just straight–up difficult or impossible to get into a lot of the off–campus housing,” he says. While Luke has ramps in his dorm room that he can use to deal with stairs, he can’t always tell if a building is, in fact, accessible—a night out might involve him and his friends troubleshooting with no guarantee of success, since ramps won’t always work. For Luke, “sitting in Harrison 3rd floor” isn’t his idea of fun either, but on a Thursday night Smokes' is up the stairs, which is, as Luke explains, “a bummer because I’m great at Quizzo and I would mop the floor”. Unfortunately, though, “There’s no real way to sugarcoat that. There’s no silver lining there — it just sucks,” Luke explains soberly. Mike too laments the inaccessibility of Smokes', and while he’ll gladly take the ground floor table, ideally he’d love for Smokes' to be more accessible.

Though the logistics of joining a frat prevented Tanner from going Greek freshman year, other challenges have also colored his social experiences at Penn. When introducing himself to others, Tanner recalls that people might return the introduction, but go on to ignore him otherwise—whether that’s because he’s a stranger or using a scooter he can’t say for certain. He found his social circle in the computer science department where he has worked as a teaching assistant, but notes the challenge of creating a broader casual social circle. “I don’t have a lot of friends that I’ve made outside of computer science though,” he says, “so I think that might be a telling factor that it has put some barriers up, yeah.”

Similarly to Mike, Julianne joined Greek life and has had a positive experience thus far. Because only two out of eight of sorority houses are wheelchair accessible, Julianne met representatives from different sororities in a more intimate setting in on–campus facilities with the help of the Office of Fraternity and Sorority Life. For Julianne, joining the Alpha Delta Pi sorority was about meeting people and making friends. It also “holds people’s feet to the fire,” forcing them to get to know her or, if they avoid it, making them admit that it’s an issue with her disability. So far though, her new sisters have offered to help her up the chapter house stairs and carry in her wheelchair. “That’s awesome because normally I have to do most of the work in terms of how can I not inconvenience other people,” she says.

While the logistics of social life may always be more difficult for those with physical disabilities, as Mike explains, “The message I really want to get across is you shouldn’t feel discouraged from trying things because you have a disability.” As Julianne says, everything just “takes longer” with a physical disability, including building a social life, but social life for students with physical disabilities is not nonexistent.

It’s Not What You Think

Despite the difficulties students with physical disabilities might face at Penn, they want you to know they’re still doing just fine.

“I know that the people who worry about me the most are the people who know me the least, alright?” quips Julianne, who also calls out the assumption that she must be miserable because she uses a wheelchair when that’s just not the case. “You can’t control that any more than I can control my abilities.”

Luke acknowledges that there are extra obstacles in his way. “But that doesn’t mean that I’m sitting around feeling sorry for myself the whole time, because I don’t really know any other way to live besides this,” he says. Luke still takes walks to the Delaware River when the weather is good. “It’s annoying to have to feel like the sportsman all the time,” he says, “because no one’s never seen someone in a wheelchair and no one knows how to act even though everybody has and everybody should, just treat them like people.”

Luke acknowledges that there are extra obstacles in his way. “But that doesn’t mean that I’m sitting around feeling sorry for myself the whole time, because I don’t really know any other way to live besides this,” he says. Luke still takes walks to the Delaware River when the weather is good. “It’s annoying to have to feel like the sportsman all the time,” he says, “because no one’s never seen someone in a wheelchair and no one knows how to act even though everybody has and everybody should, just treat them like people.”

“I don’t let it define me. That’s why I’m here, and I think that some people, maybe if they’re more severely disabled, they don’t have the opportunity to not let it define them, but to the extent that you can participate in things, just go for it,” says Mike.

As students with physical disabilities go about their days, as Dr. Cohen might say, Penn at large should have its eyes on potential problems. As Luke notes, it’s not about rushing to help him open a door that he can open himself, and, as Tanner explains, he doesn’t want to be reminded of his disability all the time. It’s something as small as not using the accessible stall in the bathroom when there are several others open, as Julianne suggests, or letting SDS know if you notice a problem. It’s something as simple as breaking the ice with a question about how their day is going, not asking how fast their wheelchair or scooter goes.