An answer to “where are you from?” should come easily enough; and for most people, it does. After all, even if you were born, say, to immigrant parents, you can almost always think of home as Genericville, XYZ.

I’ve never really experienced that ease.

As children, my Lebanese mother and Syrian father emigrated to Melbourne, Australia, where they met and where I was born some time later. So, at the age of five when my family and I moved to the UAE, I didn’t fully realize that Dubai was where I would spend the rest of my childhood and teenage years.

Growing up in a city so colourful and eclectic was how my long and tumultuous journey in discovering my identity began. I remember that once I wore an Australia jersey, a kangaroo cap, and a miniature koala to school. It was year 7, at a sort of mixer called the World Food Day, where all students had to proudly represent their respective home countries.

“Why are you wearing that? You’re not Australian,” said one of my classmates, who was the first to ever call my ‘Australian–ness’ into question. That day, when I was talking to my mother after school, I put my thoughts into very simple words: “Mum, I don’t think I’m Australian.”

Some years passed between that moment and the day I arrived at Penn as a freshman in the Huntsman program. At that point, I had already begun to embrace my Syrian–Lebanese roots: I remember that, on our short trips to Australia, my family and I would visit not granny and grandpa, but Teta and Jido. Their large family barbecues, complete with hummus and other mezza, were radically different from the typical Aussie lunches of vegemite sangers.

I knew I wasn’t Australian—but, turns out, I wasn’t Arab either. My “Arab–ness” was missing two critical components: language and citizenship. My father made it a point to teach me the complexities of written Arabic and its grammar, and although he did help me to grasp them, I never quite developed them.

But it’s not like I didn’t try—my school offered a special curriculum which allowed Arabs to learn Arabic, but the fact that I was not an Arab national kept me from following it. As most Arab countries define nationality and citizenship by patrilineal descent, I was, and still am, ineligible to claim my Lebanese citizenship. And, while in theory I am eligible to apply for Syrian citizenship, I don't feel comfortable doing so.

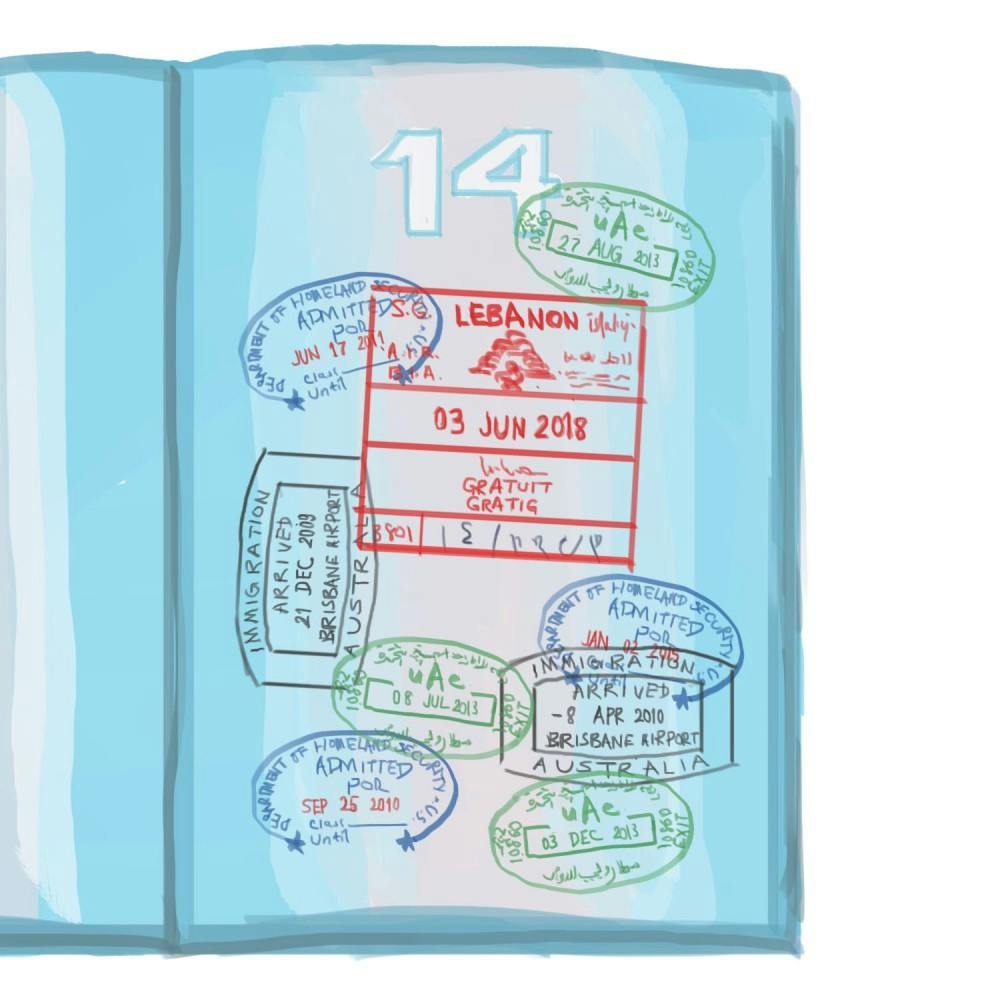

Given the current state of world affairs, as well as the unpredictability of the Trump administration’s foreign policy, the symbolic gain in officially ‘becoming’ a Syrian is not worth the risk. That would, of course, substantially increase the probability of a 'random check' at the airport. But, more importantly in today's world, there's a strong possibility of being denied entry into the United States altogether.

When planning to study abroad in Lebanon, I had to apply for a visa. The feeling of having to do that to study in a country I consider to be my own is painful enough, and to have the government deny my roots in that country only makes the feeling worse. When I went to the Lebanese Consulate in New York to process my visa, I spoke to the officer in Arabic, with a heavy Lebanese accent. He was confused, assuming that I was a Lebanese citizen.

I did end up spending the spring of my sophomore year studying abroad at the American University of Beirut and was hoping for an opportunity that would help me find home. But that’s not exactly how things went.

Before living in Lebanon for six months, I felt very comfortable in my Arab identity, in a way that everyone recognized. But I was not unlike children born in the diaspora: the tinge of my native English that smeared my spoken Arabic created an invisible divide between myself and the Lebanese that grew up in Lebanon.

I felt plunged back into that unknown that I hated so much, not knowing where I was really from and what my identity really was. Then, surprisingly, I found it.

While in Lebanon, I took a class designed for native speakers; not a language class for foreigners, but rather like taking a class in the English department. For the first time in my life, I felt that simple comfort I thought of as home. I was in a classroom surrounded by people from my country, speaking entirely in my heritage language. I belonged.

The class was centered around identity, and the professor made a point to initiate meaningful discussions on that theme. Interestingly enough, I didn’t think there would be any. After all, we were, for the first time, all Arabs.

But at the end of the day, nobody’s identity can be boiled down to one word, or even a few of them. As my own experience taught me, there are so many elements that factor into that concept, from language to ethnicity to religion to gender to country of birth, and so many more. But the most important part of our identity is that we get to define it on our own.

I’ve come to realize how important it is for the ‘third culture kids’ to think about how they choose to identify themselves. I spent most of my life allowing others to affect the perception of my own self, until I studied abroad and finally found the simplest way to deal with it: on my own.

So, I am Syrian–Lebanese. Yes, politics and uncertainty in immigration policies deny me the right to the citizenships of my homelands. And yes, other Syrians and Lebanese point out the occasional slip–up in my spoken Arabic. Yes, my identity is a mosaic; but my story is my own to tell, and it is constantly evolving.

Jonathan Lahdo is a junior in the Huntsman Program in International Studies and Business. His focus language is Arabic.