At last, Donda is here.

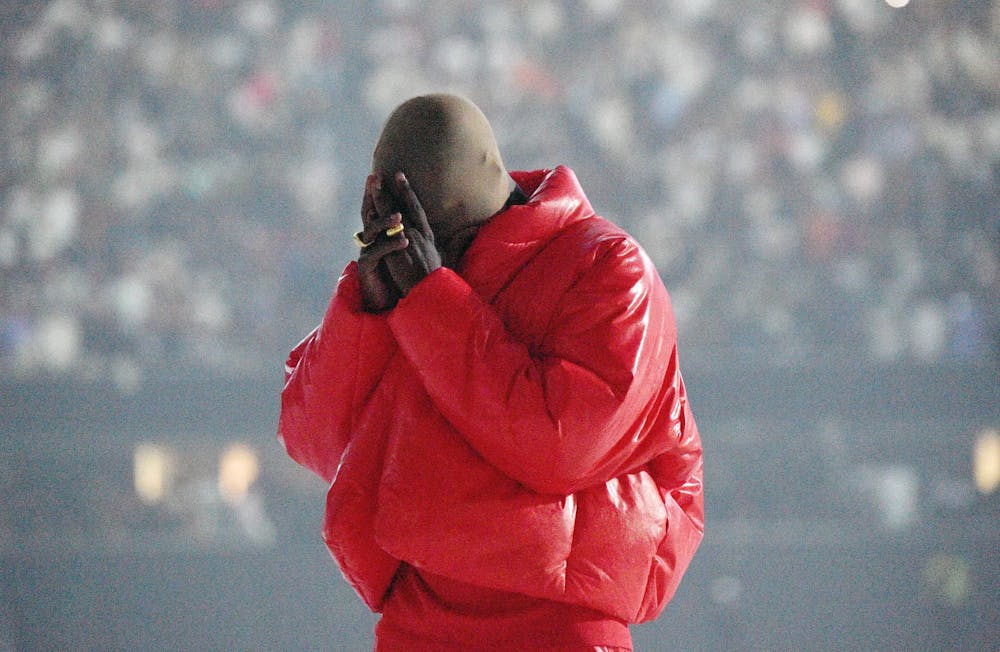

One of the most (if not the most) anticipated albums this year, Donda arrived on Aug. 29 after a series of unrealized release dates. Kanye West—who is purportedly changing his name to the mononym “Ye”—initially announced a July 24, 2020 release date, which came and went. Then, he made the album a real possibility by hosting a “listening party” earlier this summer, then a second, then a third, before actually releasing the album.

While certainly unconventional, the listening parties allowed us to see the album’s metamorphosis in real time; with each successive event, Donda became a little longer, a little more collaborative, and a little more fleshed out. The events themselves became more surreal: the first event had a masked Ye simply running around a stadium playing tracks while the final one involved Ye self–immolating and perhaps remarrying his ex–wife, Kim Kardashian.

The album itself finally dropped on Sunday morning (apparently, against Ye’s consent), and it’s long. Clocking in at one hour and 48 minutes, the album is longer than his previous three releases combined. It's also deeply collaborative; almost every song features extended vocals from other artists, creating a sonic diversity as the genre shifts from track to track. In these respects, Donda is exceptionally reminiscent of 2016’s The Life of Pablo.

Pablo was actually unfinished when it dropped—Ye famously made alterations to the album for months after its release, claiming that the record was a “living, breathing, changing creative expression.” Upon first listen, Donda is similarly raw, with some tracks needing further mixing and others lacking cogent endings. And then, of course, there are the censored profanities that distractingly remind us that Ye hasn’t escaped his commitment to making clean music. Can we expect new versions of Donda over the coming weeks and months? Will a review written mere days after the record’s release become painfully outdated?

It’s unclear. Yet, even at this point in time, there are moments on Donda worthy of praise. On "Jail," a powerful opening to the album, the harsh guitars provide a minimalist rhythm that complements a sharp verse from Jay–Z, suggesting a possible ending to their years–long feud. "Hurricane" features a beautiful chorus from The Weeknd, and a very catchy hook from Ye, where he begins his verse with a sassy “Mm mm mmm mmm mmm.” While Jay–Z and The Weeknd are long–time collaborators of Ye, he also enlists the help of newer sensations, like Roddy Ricch on "Pure Souls," who laments how fame and money can allow someone to reinvent themselves fundamentally—for better or for worse. Ricch pointedly asks, “The truth is only what you get away with, huh?”

"Jonah" and "Moon" are the true emotional highlights on the record, beginning with melodic choruses that provide a depth that the other cuts on the album simply cannot. On "Jonah," singer Vory opens with a beautifully sung chorus, asking, “Who's here when I need a shoulder to lean on? / I hope you're here when I need the demons to be gone / And it's not fair that I had to fight 'em all on my own.” Don Toliver opens "Moon" with a similarly vibey chorus sung over an electric guitar that accompanies Kid Cudi’s yearning hums.

The best moments on the album, however, are when Ye is able to do what he is known for—flipping samples and reimagining established sounds. Despite its awkward ending, "Off the Grid" is easily the best track on the album, showcasing the fact that Ye can keep up, despite the fact that he’s been at this for more than two decades. A hard–hitting banger over a drill beat, "Off the Grid" manages to make Playboi Carti sound good—which isn’t an easy feat—and features a lengthy verse from Fivio Foreign, whose tight flow is the highlight of the track. Another absolute gem is "Believe What I Say," a track that Ye teased almost a year ago. Constructed around a Lauryn Hill sample, the track has a groovy bassline and a beat that forces you to tap your foot along. The track also features Ye’s best verse on the album, a series of well–delivered bars without any cringy lyrics (something we’ve all unfortunately learned to expect from him).

The final highlight is the nine–minute long "Jesus Lord," the thematic center of the album, and one of the few tracks that Ye carries almost entirely by himself, save for a Jay Electronica feature. Anchored around the repetitive titular refrain, “Jesus, Lord,” Ye raps about his mother, his youth, and the justice system in America. In fact, the track ends with a monologue from gang leader Larry Hoover Jr. about America’s broken criminal justice system, and how it can disrupt families.

But apart from these moments, Donda is filled with mediocre and unfinished fillers that detract from the true golden moments. Tracks like "Junya," "God Breathed," and "Tell the Vision" are unnecessary and contribute nothing thematically or sonically to Donda. Other tracks are utterly unimaginative, lacking the single quality that makes a Kanye West album so groundbreaking. "New Again" could simply be a cut off of 2007’s Graduation, "God Breathed" sounds like something that wasn’t good enough for Yeezus, and "Praise God" seems like "Wash Us in the Blood" with a longer Travis Scott verse.

In general, Donda is good—and at moments, is excellent—but lacks the sense of completeness and thematic cohesiveness that defined Ye’s older work. It also lacks the brevity that made albums like Yeezus and Kids See Ghosts so powerful and innovative. Furthermore, the elephant in the room is some of the collaborators that Ye recruited. At his third listening party, he brought out DaBaby, who recently delivered, then doubled–down on, homophobic remarks, and Marilyn Manson, who has been accused of sexual assault by several different women, making headlines for such flagrant support of some of the worst that the music industry has to offer. Though Manson and DaBaby only feature on a remix, the media frenzy surrounding them distracted from perhaps an even bigger affront: Ye’s collaboration with Chris Brown, a cyclical abuser who somehow seems to hover just above cancel culture.

Ye featuring these individuals is indefensible and alienates large swaths of listeners. After all, it’s hard to enjoy an album when it reminds you of and profits off trauma. That said, the deluge of negative reviews for Donda are perplexing, often using the social weight of the album to ignore commenting on the music. The Independent, for example, gave Donda zero stars, saying that “Marilyn Manson’s inexcusable presence leaves a sour taste that no amount of gospel can cleanse.”

Sure, such a review misses Ye’s history of being intentionally provocative and attention–seeking ahead of his album releases, but where does the line between publicity stunt and platforming an abuser lie? Does collaborating with an abuser carry the same moral weight of being one? I’d argue probably not, but it brings into sharp relief the responsibility music industry power brokers have. A quick Google search reveals dozens of artists Ye could’ve featured ahead of Manson, all of which capture that same grating sound quality. And while we could chalk Manson’s feature up to a ploy for attention, we can also ask a bigger question: Can the music we listen to exist separately from the inequalities that reinforce homophobia and misogyny?

I don’t know, but Donda has certainly made me ask.