I saw it, you saw it, we all saw it: the White House’s Instagram post featuring an illustration of a tearful immigrant in handcuffs, inexplicably resembling a screengrab from a Studio Ghibli film if Hayao Miyazaki was really into Triumph of the Will. The post is hardly out of the ordinary for the Trump administration and its gleeful cruelty, yet is brings up strange sense of unease. I was surprised to find that the friends I shared it with felt the same.Although difficult to articulate it at first, one could describe it as the feeling of your favourite backwoods being replaced by a parking lot, or when a childhood sweet suddenly tastes cloying and gummy, the feeling that some fundamental connection has been severed.

The image was created using OpenAI’s GPT–Image–1 model, now accessible through ChatGPT, which is a genuine technological advancement. The model is faster, more responsive to user instructions, and eerily good at outputting images of things like hands and full glasses of wine that stumped its predecessors. Oh, and one more thing … it’s better at stealing.

It might sound like some bold retort to artificial intelligence advocates, but it really isn’t—the history of art is a history of theft. Sometimes the theft is blatant and plainly exploitative, like downloading digital art and then minting it into an NFT to be sold for cryptocurrency. Other times the stealing is no less blatant but regarded more positively—Andy Warhol takes a can of Campbell’s Soup and sells it for $9 million, Clueless takes Emma and swaps the gowns for plaid skirts, and that’s before we get to musical sampling. If we want to condemn all artists who copy, we should start with Michelangelo, who began his career by selling one of his many dupes of ancient Roman sculptures as a genuine antique, or Vincent van Gogh, who literally traced and painted over Japanese ukiyo–e prints. AI models and the underlying neural nets are training on the works of other artists and learning how to replicate their styles, as artists have done for millennia.

If it’s not plagiarism, is the unease just a reaction to the image’s digital origins? Not if on valued their life. If I were to walk into a workshop in Tangen Hall today and start tut–tutting about digital art not being real art, I’d first be laughed at, then unceremoniously beaten to death with Wacom tablets. Art made with digital tools has won Grammys, Oscars, Tonys, and quite possibly every other award you can think of. CGI, 3D modeling, and digital mixing are just a few of the tools that artists have used to create worlds and tell stories that would simply be impossible without them. Additionally, a fact often neglected in discussions of digital art is that many tools are beneficial not because they unlock some extraordinary new capability, but because they do something cheaper and faster. AI certainly does, but I think that’s where the sinking feeling in my stomach begins.

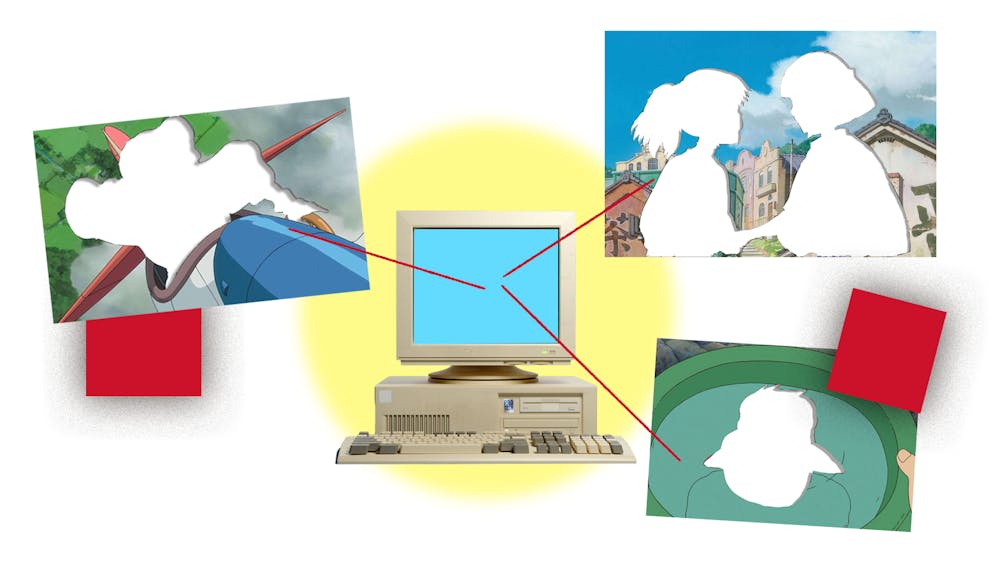

GPT–Image–1 seems convincingly more human than it lets on because it has a great sense of irony. The model has gone viral for mimicking the animation world’s proudest Luddite—Studio Ghibli insists on animating its films by hand, meticulously painting each scene frame by frame. The same ethos extends to the stories they tell, almost invariably of a young protagonist rejecting the ills of modern society and technology in favor of the human and the natural. Hayao Miyazaki and his partner Isao Takahata have devoted a lifetime to imagining worlds where who we are matters more than what we have, where our connections with the environment and with one another are stronger than any piece of metal. This connection is what allows Chihiro to rescue her parents from a life living as pigs in Spirited Away, Nausicaä to broker peace between the two great empires of her world in her film, and the titular Princess Mononoke to save her forest from destruction by resource–hungry mercenaries. AI’s potential to reshape the world for the better is undeniable—yet it remains everything Ghibli is not. ChatGPT is a faceless text box pretending to be feel, backed by hulking datacenters, rows and rows of identical machines whose arrival signals the destruction of the natural environment for miles around, powered by poison–belching power plants, and made by blasting ugly holes in the earth to extract cobalt and other minerals.

If Studio Ghibli made a film about ChatGPT, it would be the villain.

I don’t share Ghibli’s fear of technology, but I share its fear of what it makes us value. Some people will follow Trump’s footsteps and use AI to project hate, but most AI Ghibli pastiches come from people who are interested in, say, putting an old family photo in a beautiful style. The technology isn’t being praised, however, for the sharpness of its linework or its use of color. Instead, the focus lands squarely on how cheap and fast it works, how easy it is. AI art advocates argue that AI is lowering barriers, and I don’t disagree, but I think they are lowering the barriers between art and commodity. In our rise–and–grind, buy–more–be–more world, we are incentivized to monetize everything, to constantly think about how we can generate more currency in less time. Dollars, clicks, followers, we run through the streets calculating calories per hour and climb mountains estimating how many likes we’ll get with a selfie at the summit. Art might be the only thing we still do for the sake of doing it. The spiritual commitment, the unquantifiable and innate satisfaction in creation, is the value.

AI art has been around for over three years now, some of it objectively quite beautiful, but it’s no coincidence that it only started to make headlines when it gained the ability to convincingly mimic human artists. If Studio Ghibli had not devoted decades to painstakingly hand–painting each and every line, every microscopic change in expression when a character falls in love, every beam of sunlight hitting a pristine pond, we would dismiss these AI Ghibli images as hallucinations. Their value comes solely from their connection with the very human hope and happiness that the very human artists at Studio Ghibli invested their work with. I have every confidence that the brilliant engineers at OpenAI or their rivals can make AI–generated images beautiful or top a series of benchmarks, but they won’t be art. Without the human effort and thought that animates them, these images are spirited away from everything that makes art worthwhile.