Horror films have always reflected society’s deepest fears and anxieties. From monster films like Frankenstein and Dracula to iconic slashers such as Halloween and The Prowler, horror has shifted in waves that reflect the artistic climate of its time. Yet, historically, the genre has had a bad reputation for being cheap, lowbrow, and repetitive. Within the last decade or so, however, a new, semi–controversial type of horror film has emerged—elevated horror.

What does that even mean? In its simplest form, elevated horror describes contemporary horror films that emphasize psychological depth, social commentary, and emotional storytelling. The use of this term, though, can come off as somewhat pretentious. What makes one horror movie more “elevated” than another? Beloved franchises like The Texas Chainsaw Massacre, Friday the 13th, and Scream are filled with traditional jump scares and follow a clear formula. These examples are ingrained in pop culture for their iconic killers, death sequences, and reputation as a sort of time capsule for their respective decades. These franchises elevated the horror genre, yet they’d be classified as the opposite of elevated horror.

Perhaps the real shift isn’t the horror itself, but the way we talk about it.

After all, as one of few genres that leverages violence and fear to probe meaningful conversation—horror has always held subversive potential. Maybe that’s the reason why this shift is happening. For horror fans and critics alike, justifying horror as “smart” may be less about the films themselves and more about the need to validate a historically maligned genre.

Take Scream, for example–a franchise that may not necessarily be classified as elevated horror but is a clear early example of how horror can be used for greater social commentary. It critiques how real–life violence is sensationalized for entertainment and media spectacle, turning trauma into a commodity. In doing so, the film redefined horror and created its own subgenre: meta–horror. Nevertheless, at face value, it just seems like a typical, formulaic slasher.

That said, modern audiences desire to find depth and legitimacy within the horror genre; a way of destigmatizing and reclaiming a genre worthy of respect.

Today, A24 is a defining force in modern horror—elevated horror—pushing out some of the most successful, talked–about films over the last decade, like Ari Aster’s Hereditary and Midsommar to Ti West’s X franchise—arguably the most iconic horror franchise of this decade. Most recently, A24 released Bring Her Back, the second film by twins Michael and Danny Philippou, following their directorial debut Talk to Me. Bring Her Back is a dark, grimy, nasty, brilliantly miserable slow burn that dives into the occult and utilizes body and psychological horror to its fullest extent. But at its core, it is a story of grief and loss— not an uncommon theme, but when done properly, it sticks with you long after the credits roll.

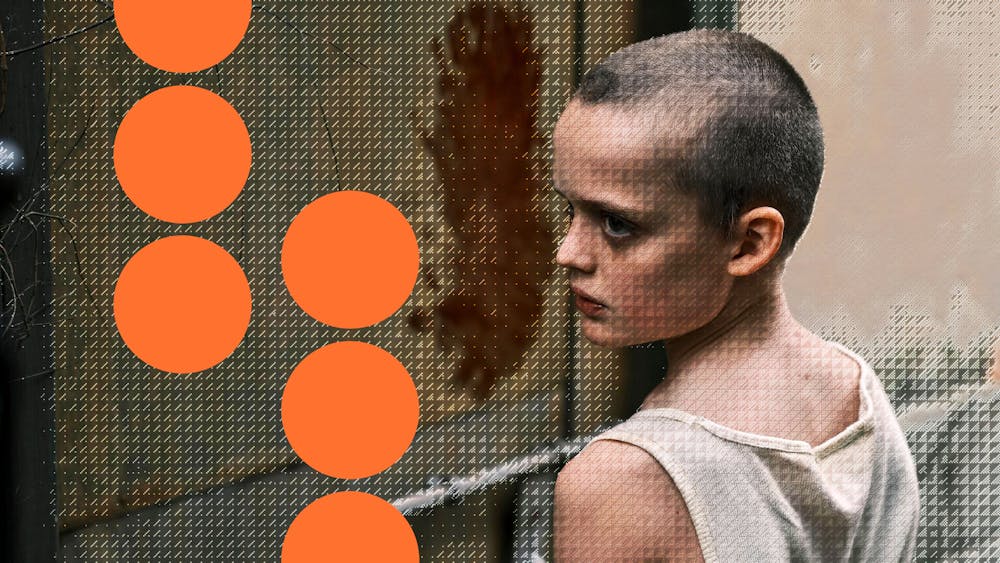

Although this is only their second film, the Australian YouTubers–turned–filmmakers have a clear narrative and visual style. Like Talk to Me, Bring Her Back follows two siblings whose lives become more complicated due to someone else’s encounter with the occult. The film opens with a found–footage sequence of a resurrection ritual, which anchors its tension and hints at a possible connection to the Philippous’ first film. After this prologue, we are introduced to Andy (Billy Barratt) and his younger stepsister, Piper (Sora Wong), who is visually impaired. Their lives turn upside down when they are forced into the foster system following Andy’s father’s death. In a system designed to keep them apart, Andy advocates to be placed with Piper. Both siblings end up in the care of Laura (Sally Hawkins), an emotionally–fractured woman whose own visually impaired daughter recently drowned in a pool. When the siblings arrive, they are also introduced to Oliver (Jonah Wren Phillips), Laura’s adopted son, who is mute and eerily disassociative.

It doesn’t take a genius to figure out early on that something is wrong, that these children are part of something far more sinister than they realize.

One of Bring Her Back’s greatest strengths is its cast. The actors’ raw, emotionally grounded performances made me more invested in the story. Barratt, in the role of Andy, does a wonderful job capturing the emotional complexity of his character. The fact that this is a 17–year–old character played by an actual 17–year–old makes a huge impact in sustaining the tone of the film—you never forget that this is a kid who has the weight of the world on his shoulders. As for Wong, it’s great that the Philippous were able to cast an unknown actor and trust them with such demanding material. Wong is also visually impaired in real life, providing more authenticity to her portrayal of Piper.

The biggest standout performance in the film is Sally Hawkins as Laura. From the moment you meet her, she is very off–putting, reminiscent of Pamela Voorhees from the original Friday the 13th—tragic and grief–consumed, a mother in mourning. As the film progresses, she becomes a nerve–racking freak who really gets under your skin. The psychological warfare Laura wages against Andy throughout the film makes it easy to root against her. But that clarity only makes the fallout more devastating—when all the characters’ efforts, however desperate, amount to nothing.

Apart from the film’s performances, its body horror made the viewing experience quite tense. In one scene, Andy is left alone in the house with Oliver, who was locked away in a room by Laura. Andy lets him out of his room, prepares food for him, and suddenly, Oliver is biting and chewing on a knife, spewing out blood and pieces of his gums and teeth in the process. Throughout the film, Oliver’s demonic possession becomes clearer—his condition tied to Laura’s desperate attempts at resurrecting her deceased daughter. The character emerges as central to the film’s disturbing imagery and its psychological tension, personifying Laura’s grief and loss of humanity.

Although the themes of grief within Bring Her Back aren’t revolutionary or unheard of, the Philippous do a great job establishing their style and artistic contribution to the genre. Alongside this theme, the film uses horror to critique the limitations of the foster care system, a system designed to protect vulnerable youth. Bring Her Back may be classified as elevated horror, and importantly also a very good story. It is elevated in a sense that there is more to the narrative than just thrill and gore—but also because it was made by people who care about horror and its potential to create meaningful conversation.

The Philippous may be new voices in the genre, but their creative control and cinematic confidence show that they are here to stay. Given A24’s track record, the future of horror is in very good hands.