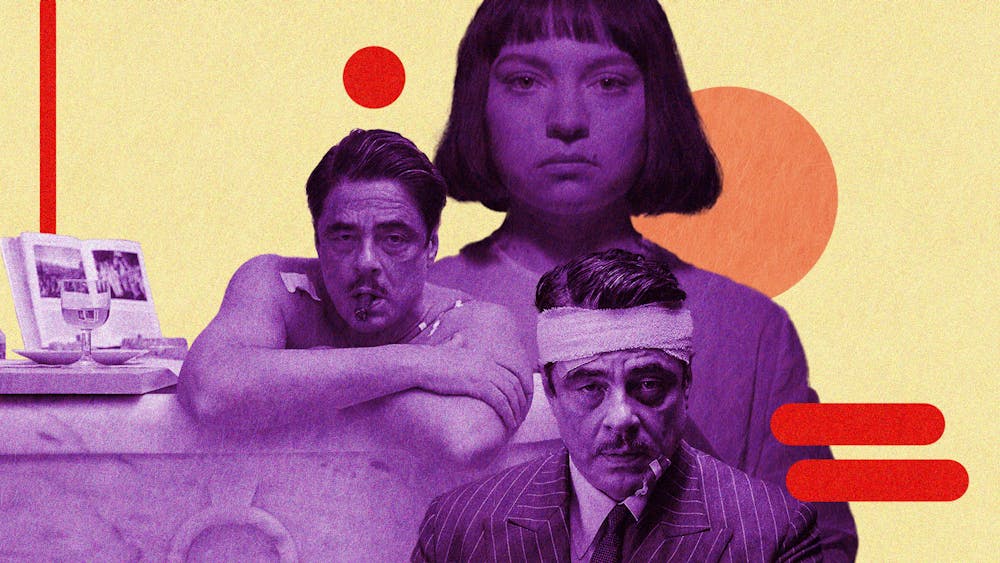

Within the first ten minutes of Wes Anderson’s The Phoenician Scheme, Anatole “Zsa–Zsa” Korda, an enigmatic industrialist played by Benicio del Toro, shows the audience exactly who he is. Reclining in his private jet, he hears a faint clicking outside the fuselage. Moments later, his assistant’s torso explodes in an absurd display of gore—a failed assassination attempt, one of many in his high profile life. Unfazed, Korda strolls into the cockpit, violently unseats the pilot, and crash lands the plane into a Midwestern cornfield. As with each of his previous assassination attempts, he miraculously survives.

This opening scene is characteristic of Korda’s reaction to danger. From getting shot to sinking in quicksand, he constantly shrugs off precarious situations, simply saying, “Myself, I feel perfectly safe.” It’s this repeated mantra that comes to define Korda, a man whose pain from being abandoned as a child has hardened into an intense detachment. He deflects his paternal responsibilities and hires nannies to care for his nine sons, who live in a separate bunker building on his estate. Rumors suggest he murdered all of his former wives. In classic Andersonian fashion, our protagonist is theatrical and emotionally fractured.

Moreover, what sets The Phoenician Scheme apart from Anderson’s earlier work is the unlikely relationship Korda develops with his daughter Liesl, played by Mia Threapleton. Sent to the nunnery at a young age, Liesl reunites with Kordaafter his latest near–death experience. Like her father, she is built of an icy exterior, however her upbringing as a nun instilled in her a deep spirituality, alongside a strong moral framework that brings her into constant conflict with her father. After Korda outlines his plan to make a fortune by investing in the infrastructure of Phoenicia, Liesl immediately challenges his use of slave labor, refusing to help him unless he agrees to pay his workers.

Korda’s interactions with his daughter force him to reckon with his past. Her blunt authenticity continually holds him accountable for his morally ambiguous actions and interrogates what has caused his characteristically heartless behavior. Korda begins to process trauma he has long suppressed by envisioning himself as the defendant in a divine court, where he attempts to justify his wrongs. The film’s emotional climax sees Korda paying his debts and retiring to live a simple life, following his realization that his relationship with Liesl is worth far more than his reckless business ventures.

Anderson further explores the importance of human relationships through Michael Cera’s character Bjørn, a Norwegian intelligence agent originally sent to spy on Korda’s business empire. He, too is softened by his love for Liesl, eventually abandoning his mission entirely because of his bond with the family. Through both Liesl and Bjørn, The Phoenician Scheme posits that love, in any of its forms, has the power to crack the armor of even the most hardened individuals.

The Phoenician Scheme also goes beyond the personal arcs to explore the politics, circling around themes of tyranny and repression at the hands of the wealthy. Korda’s fortune, built on questionable ethics and endless resources, becomes a kind of exaggerated allegory for the massive hoards of the real ultra–rich. For most of the film, he operates within a system where power and wealth extraction justifies near endless cruelty. In this way, Anderson subtly critiques not just the hoarding of wealth but the emotional and spiritual emptiness that comes with it. Korda’s emotional journey represents an optimistic take on how the capitalist elite might overcome their inhumanity. The ending, though idealistic on the surface, begs the question: What might the world look like if the ultra–wealthy chose decency over domination? In Anderson’s hands, this imagined society isn’t a utopia but a fragile possibility—it hinges not on sweeping revolutions but on small, personal shifts in conscience.

The Phoenician Scheme’s painting–like visuals—saturated, symmetrical, and often surreal—mirror Korda’s psychological state: orderly, yet ornate and complex. In dream sequences especially, Anderson’s signature aesthetic becomes a vehicle for portraying Korda’s emotional journey. It is without surprise that Anderson’s deadpan humor lands immaculately amongst the audience, serving not just as entertainment but doubling as an amplifier of the film’s thematic undercurrents.

Overall, The Phoenician Scheme feels like a more spiritually mature cousin to The Royal Tenenbaums and The Life Aquatic with Steve Zissou. Korda isn’t a man–child using grand gestures to redeem himself—inspired by those around him, he questions the principles he has lived by his entire life. Like The Grand Budapest Hotel, The Phoenician Scheme is a showcase of Anderson’s nuanced worldview, displaying a grounded realism that is complemented by his typically whimsical visual style.