What does it mean to be a virgin when your body has never truly been yours?

In Lorde’s fourth studio album Virgin, she isn’t chasing purity, but tearing the very concept of it apart. Across eleven tracks that are simultaneously vulnerable and defiant, she unpacks gender expectations, bodily autonomy, and the uneasy freedom of growing into a self that the world isn’t ready for. It’s an album that sounds like it’s reclaiming space in real time: for queerness, for rage, for softness, and all of the weird in–between.

Since her breakout at sixteen with Pure Heroine, Lorde has built a career on redefining the pop genre and peeling back its layers, first as a young outsider, then as an emotional surrealist on Melodrama and Solar Power with her lyrics and synth–focused approach. But Virgin feels and sounds different. For Lorde, the album showcases a new self as well as a new sound. In response to years of scrutiny claiming her albums are overproduced or have lost relatability, Lorde asks in Virgin who gets to define her, refusing to explain herself or her work. Her most genuine and emotional project to date, Virgin arises from the conflict between Lorde’s private truths and her public perception.

The album’s first single, “What Was That," was released on April 24th and immediately sparked excitement for the new album because of its unique sound and production. The second single, “Man of the Year,” was released on May 29 and was catapulted to greater success through of a trend that inspired by it on social media. Scrolling on TikTok post–album release, you’re likely to see videos that feature the chorus of the song, “Give it up for the man of year,” accompanied by screenshots of texts people have received from their boyfriends, husbands, dads, and others, sarcastically criticizing them for not living up to basic expectations.

Despite its cleverness, this trend ultimately falls short. Rather than merely making fun of manhood, on "Man of the Year," Lorde challenges it from the inside out with lyrics such as, “How I hope that I'm remembered, my / Gold chain, my shoulders, my face in the light, oh / I didn't think he'd appear.” It is a layered critique of masculinity and a playful exploration of gender. The song is intended to be a gender–bending performance that explores power, illusion, and the absurdity of masculinity and its norms. By repackaging it as a meme about toxic boyfriends, the internet risks flattening the song’s complexity into a punchline. It’s a reminder of how quickly audiences can reduce vulnerable, provocative, and queer art into a gimmick, even when it’s speaking directly about queer experiences and identity.

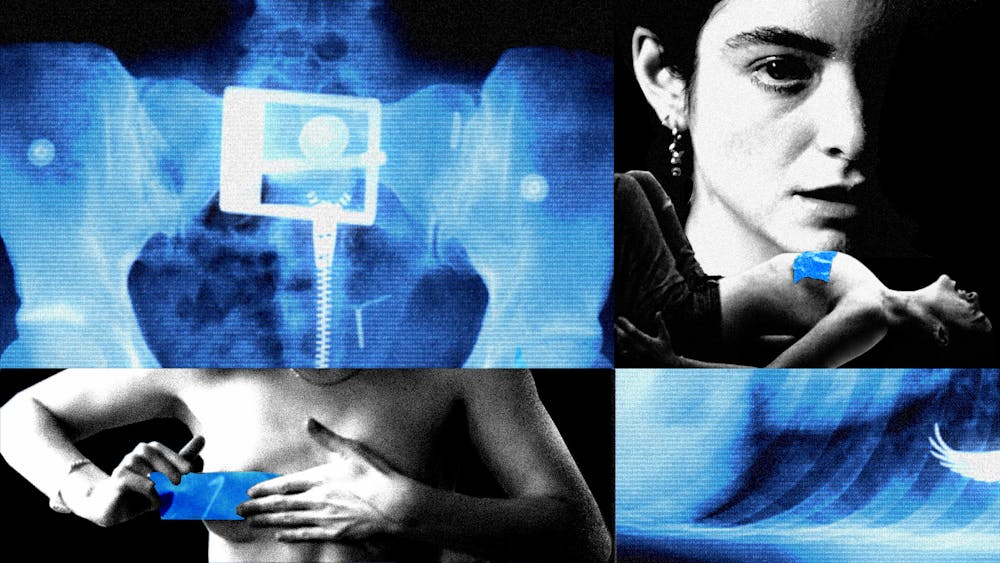

The contradiction is even sharper with the song’s music video, which has a very different mood from the viral trend. Lorde sits in a stark, sand–filled room, barefoot and dressed in men’s jeans and a white tee, which she then removes before binding her chest with duct tape and singing the lyrics leading up to the chorus. The entire video is stark, quiet, and almost ritualistic in nature. The visuals are stripped–down, raw, and ambiguous, with no audience or performance catering to the male gaze. It is just Lorde, inhabiting her body and voice on her terms, with facial expressions and deliberate movements in the sand that convey a quiet but committed resistance. In an interview with Rolling Stone, she talks about how she wanted the song to be “fully representative of how [her] gender felt in that moment.”

The contrast between this and the sarcastic TikToks is stark. Where the trend utilizes the song’s chorus for laughs, the music video and lyrics taken together form a critical meditation on identity, ego, and embodiment. The dissonance points to a broader issue: how easily public discourse—especially on social media—reduces complex explorations of gender and selfhood into palatable, shareable content.

“Man of the Year” is just one piece of the album’s larger tapestry. Throughout Virgin, Lorde returns to her body again and again, not as something to be beautified or protected, but as something to reimagine and reclaim. The album resists any clear classification by genre, which is precisely the point: Virgin is about the spaces between definite identities—between being a woman and a man, between submission and control, and between vulnerability and defiance. It’s in that in–between space that Lorde finds a new kind of freedom, where she doesn’t ask for permission or feel like she has to.

The album unfolds like a fractured mirror, each track representing a different perspective on identity, embodiment, and self–definition. It doesn’t present answers, but instead showcases mood swings, shape–shifts, and quiet revolutions.

The album’s first track, “Hammer,” opens with a declaration that feels both personal and political: “Some days I’m a woman / some days I’m a man.” Lorde doesn’t just declare her fluidity, but constructs the entire album around it. The production is stripped back and deliberate, echoing the weight of the song’s title. The choppy synth sound at the beginning of the track is reminiscent of an MRI machine, reflecting the album’s cover and suggesting that the tracks that follow reveal who Lorde truly is, both inside and out. There’s a tension throughout between softness and blunt force, like she’s smashing apart the expectations placed upon her while simultaneously building something more honest in their place. “Hammer” sets the tone for Virgin as an album uninterested in binaries—whether in terms of gender, genre, or emotional clarity.

The second track, “What Was That,” reflects the chaos of not being fully present in your own body. The vocals echo, blur, and warp as Lorde navigates the disorienting space between self and public perception. The title itself feels like a fragmented thought—confused, half–remembered, and questioning itself. It captures the feeling of trying to reclaim both your body and identity after years of their being shaped by others' perceptions. “What Was That” isn’t about clarity; it’s about the mess of unlearning gender expectations and norms. There’s a haunting tension here, and in that tension, Lorde finds a kind of truth.

In the third track, “Shapeshifter,” Lorde leans into gender as a performance, trying on personas with ease and abandon. As though she is putting on different costumes, her voice stretches and changes throughout the track as she experiments with texture and tone. The song is lighthearted but intense, and every change suggests a more profound fight for independence. It’s one of the most conceptually rich songs on the album, with Lorde not only resisting definition, but also reveling in ambiguity.

“Favourite Daughter,” the fifth track on the album, sounds sweet on the surface but reveals something far more complex underneath. It examines how femininity is shaped, rewarded, and ultimately weaponized, especially within the dynamics of family and fame. Lorde recounts playing the role of the dutiful, devoted daughter, reflecting on both the praise she received and the emotional costs that came with that performance. The illusion cracks as she admits she’s been “breaking [her] back just to be your favourite daughter.” Traditional femininity, in this context, becomes a trap, with performance as obligation and self–sacrifice as expectation. The track doesn’t explode with anger, but simmers with it, quietly rejecting the roles she was once praised for. It’s a confrontation with the subtle violence of being idealized, and a refusal to keep meeting the world’s gaze on its terms.

In “Current Affairs,” Lorde looks both inward and outward at once. She sings about a relationship that was doomed to failure, expressing the alienation she feels from her own life in its aftermath. She bemoans that her relationship isn’t just built on the intimacy between two people—it’s subject to ever–present public scrutiny, to the “voices we hear through the open door.” The track complicates the idea of selfhood as a private journey, suggesting that identity—especially queer and gender non–conforming identity—is always affected by being perceived.

The seventh track, “Clearblue,” explores fertility, autonomy, and the decisions that often quietly define people’s lives. Referencing the pregnancy test brand, this track could be interpreted as a meditation on choice and what it means to be in control of one's own body. The vocals are soft and uncertain, and the production is almost skeletal. The intimacy of the song is overwhelming at times. Whether the lyrics are about potential motherhood, loss, or simply the surreal experience of being in a female body, it’s one of the most affecting songs on Virgin, grounded in physical and emotional presence.

Despite its title, “GRWM” is not actually a song about getting ready. Instead, the eighth track is a meditation on the disconnect between how we’re expected to present ourselves and how we feel inside as “grown women.” By using the language of a TikTok performance and daily ritual, Lorde lures us into expecting something light or curated. What we get instead is something much more bare: a quiet grief, a sense of disassociation, and a reckoning with the passing of time. The song reads like a metaphorical explanation of how personal identity is anchored in time. In that space, Lorde questions why she’s getting ready to be the grown woman she knows she’ll never become.

The ninth track, “Broken Glass,” hurts. It is the emotional core of the whole album, evoking the feeling of trying to hold something together that is already broken. Lorde’s voice cracks in places, and the lyrics are laced with raw emotion. But there’s no melodrama here—just honesty. It’s a song about living with the aftermath of change and waiting for the scar tissue of transformation to heal, with lyrics like, “It might be months of bad luck / But what if it’s just broken glass?” Gender, identity, and the body are all present, but in fragmented form, never fully resolved.

Immediately following “Broken Glass,” the tender “If She Could See Me Now” gives the listener emotional whiplash, and that’s precisely what it’s meant to do. It’s unclear if Lorde built this song around a vision of another woman, a younger version of herself, a maternal figure, or a former self steeped in gender expectations, and it could apply to any of those. It’s soft and unresolved as Lorde grapples with both who she was meant to become and who she is now. The track blends nostalgia with sadness, but ends with a reflection on things that, although they hurt her in the past, she wouldn’t change now because they shaped her into who she is today.

Lorde saves the best for last by concluding with “David,” which feels like a revelation. It marks a turning point where she begins to separate who she is supposed to be from who she has become. There are a few theories about where this track’s title comes from—it could be a reference to Michelangelo’s statue and the feelings of being carved out by another person, a nod to David Bowie, or even a reference to a past lover. Regardless, the track brings together all the album’s themes: performance, vulnerability, embodiment, and the longing to be seen as whole, and it brings back the choppy synth at the beginning of the album with “Hammer” in a truly full–circle moment. Virgin doesn’t end with quiet resolution, but rather a final, emotionally charged release.

So what does it mean to be a virgin when your body has never truly been yours? Lorde doesn’t offer a single answer—she provides a framework. It’s one where identity is unstable, where performance is a matter of survival, and where the body becomes a site of both rupture and return. Across these songs, she doesn’t reclaim virginity as purity, but redefines it entirely: as beginning again on her terms. No longer something taken or given, virginity is something messy, defiant, and wholly hers. Virgin isn’t just a portrait of one artist in transition, but a permission slip for the rest of us to be complicated, to shapeshift, to be uncontainable—and still be real.