Cluely’s company onboarding package includes the following: a work laptop, ID, house keys, a five–motif Van Cleef, a corporate Hinge premium subscription, 74 servings of whey protein, and five honey packs. “Put it in your coffee next time,” Chief Marketing Officer Daniel Min (W ’25) advises on the company’s official TikTok page. “Trust me, it tastes great.”

If the swag bag doesn’t clue you into the kind of startup this is, its social media will: On any given scroll, you may see Min jokingly pressure his interns to hit their weekly dating quotas or come across their fursuit–clad mascot (Clue the Fox) body–slam Cluely co–founder Roy Lee.

The company, which is developing a real–time, artificial intelligence assistant to help you “cheat on everything,” raised $15 million in its most recent investment round—a feat that its investors directly attribute to the company’s digital footprint. And while it may be one of the startup world’s most prominent viral darlings, it’s not alone.

As this generation of tech hopefuls launch their various AI–powered companies (and there are plenty), it seems they are aging into a very different scene. Gone are the days of nerds building PCs in their garage—the new industry leaders are, God help us, influencers.

Or, as Min might prefer, “content creators.” Better yet, “creatives.” The 21–year–old CMO graduated from Penn just this spring, finishing up summer classes while entering his new role as chief of marketing. Min previously appeared on Street’s pages fresh from a growth internship at RecruitU but reneged on his return offer this June to join Cluely.

Since then, he’s focused on developing Cluely’s marketing operations, which, rather than product, have always been the company’s beating heart. In a fiercely competitive attention economy, Cluely is trying to grow its “mindshare” through three primary formats: “Black Mirror–type” launch videos, borderline–offensive viral stunts, and brain–rot user generated content.

Lee became infamous earlier this year for using Cluely’s predecessor, InterviewCoder, to cheat on Big Tech job interviews. Since then, he’s gotten lap dances at the Cluely HQ (which triples as a living space, workplace, and content house) and thrown a Y Combinator after–party that got shut down due to a mass influx of uninvited guests. Or, as Lee puts it, because “Cluely’s aura is just too strong.” Later this month, however, the Cluely team plans to make up for the early cancelation by hosting a $1.5 million rave.

These antics are all designed to inflame, excite, and ultimately goad Cluely’s impressionable audience into bringing up the company’s name in casual conversation. Whether you love it or hate it, if you’re talking about Cluely, they’ve won.

This viral strategy has paid off, but not without (or perhaps by) generating significant backlash. In his YouTube videos since joining Cluely, Min speaks about the many negative comments he’s received, whether from strangers on the internet or even his Penn admissions interviewer, who told Min that the company’s reputation would ruin his “Wharton pedigree.”

Across San Francisco and the tech community, criticisms about Cluely’s product and its team members abound. Depending on who you ask, its AI agent is either an existential threat, allowing unqualified individuals to sneak past job interviews, or an easily replicable “GPT wrapper” which has used irresponsible marketing to bloat its valuation, only hastening its inevitable downfall.

But perhaps they’re hating the player for simply playing the game. In today’s tech landscape, Cluely may have found a winning strategy. As companies like OpenAI, Anthropic, and Google compete to create the most powerful, humanlike AI model, they’ve often ignored the more tailored use cases of AI, such as making class curricula, autogenerating social media posts, and about anything else an imaginative–enough twentysomething could come up with.

This has left a bounty of low–hanging fruit for young tech founders. With the models already built, these individuals only need to act as “AI–powered” middlemen. They take the customer’s needs, engineer them into prompts for ChatGPT, Claude, or Gemini, and communicate the output back to their customer. The programming is relatively simple, and with this low barrier of entry has come a deluge of Gen–Z entrepreneurs looking to build the world’s next Big Tech company (or at least get acquired by one).

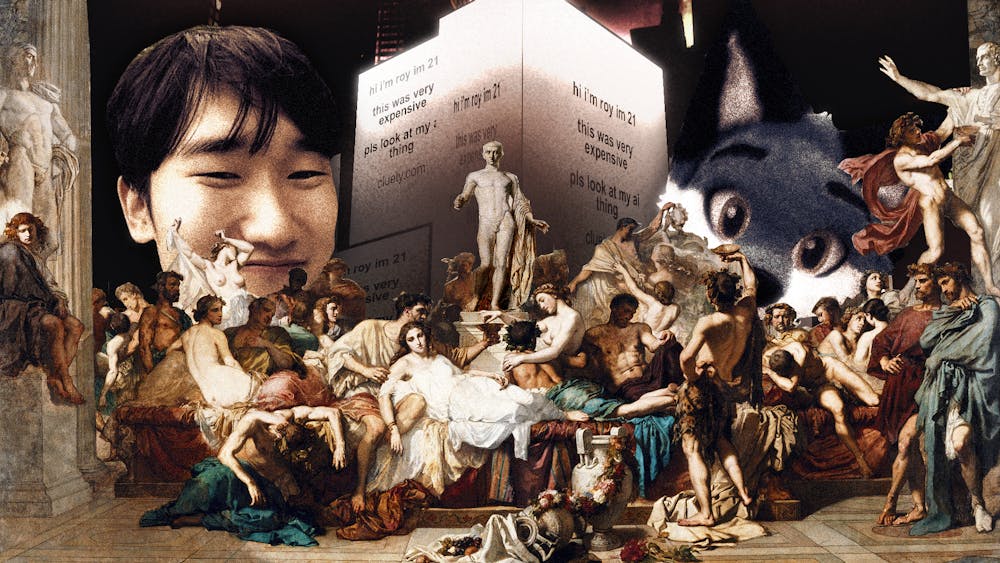

Just as with its product, Cluely’s marketing meets its young, chronically online audience where they’re at: low–lift, minimal effort. Min tells Street that despite the criticism he’s faced, he has “no concern about the branding.” In fact, he sees it as the key behind their success. “We would not have raised $15 million if our branding was not out of pocket,” he says. “Cluely is all about taking big bets on things. … I just paid $100,000 for billboards, and that’s literally just to run an experiment.” The experiment in question is currently suspended over Times Square, with eight austere white billboards reading, “hi i’m roy i’m 21 / this was very expensive / pls buy my thing / cluely.com.”

This isn’t Min’s first rodeo, either. In his junior summer, he launched socials for RecruitU, a startup designed to help college students recruit to various business jobs. After growing the company’s Instagram and TikTok pages to a combined 134,000 followers, he found the work agreeable enough to continue into the school year. Once a run–of–the–mill finance kid, Min began to enjoy small–time social media fame and was ready to commit to the role post–grad.

That’s when Lee, who had recently launched Cluely, DMed him with a job offer. “The only thing I was indexing for,” Min says, “was ‘Do I see myself being best friends with these people?’” After meeting Lee and grabbing dessert with the team, he decided the answer was yes.

Since then, the TikToker–turned–marketing whiz has been hard at work procuring Cluely’s most valuable resource—content creators. These creators live just across the street from Cluely HQ, where the company pays for all their housing. Min’s hiring process was shockingly organic.

Shortly after Min joined, creator Remy Zee (who is best known for his “you have big eyes, small face” TikTok video) began working at the company. Then, Min called his former New York roommate and fellow creator, Mino Lee. The two had planned to work in New York post–grad, but after Min told his friend about Cluely, Lee decided to join him. From there, they recruited their mutual friends Prosper, Armon, Tulio, and Aaron (“A. Drizzy”). Just like that, Min had his team of content creators who could leverage their “algo–pull” to bring in a large, loyal audience that would hopefully form Cluely’s userbase.

In a competitive market where programming talent is not always the highest priority, Cluely is just one company among a whole batch that has learned to rely on social media for success. Another such example is Series.so, led by Yale University students and co–founders Sean Hargrow and Nathaneo Johnson, the latter of whom has taken point on Series’ newest project: Love Island for startup interns. Hold for gasps (or sighs).

At least that’s how Series branded its Hamptons–based reality TV show, creatively titled The Series, to audiences last month. What was supposed to be Series’ remote internship program turned into this ambitious marketing strategy. “I didn’t even watch Love Island,” Johnson confesses. “The idea came from putting growth interns in a house in New York, and now we’re just televising it.”

Whatever the inspiration, the company’s initial posts on TikTok, Instagram, and LinkedIn have done numbers with the United States’ most chronically online preprofessionals. According to Forbes, the show is “part hackathon, part influencer house, and part startup growth stunt.” It features 12 Series interns who will compete in challenges and gradually be eliminated based on who brings in the lowest number of new users, with the winner earning a whopping $100,000.

Series, which claims to be “the first AI social network,” has a tamer reputation than Cluely: less brain–rot content, more serious announcements, and an aim to disrupt but not necessarily scandalize. Comparing itself to Facebook, this social network claims to be doing better. “We’ll be looking back and saying Harvard did it wrong in ’04, and Yale did it right in 2025,” Hargrow told the Yale Daily News this past April.

The startup was born from the founders’ desire for more accessible and organic networking experiences. In the pair’s podcast, they interviewed entrepreneurs and discovered that they could often trace back an interviewee’s success to “having the right connection at the right time.” As Johnson tells Street, their subsequent efforts to “digitize a superconnector” resulted in Series, a software which uses a team of AI agents on Messenger to connect people based on their needs—perhaps an entrepreneur with a product designer or a writer with a publicist.

The question is: Will Series’ TV venture pay off? Johnson is certainly willing to find out. “An entrepreneur, at minimum, is someone who’s taking a risk,” he says. And Johnson believes he’s paved the way for other startups to follow this trend toward flashy marketing.

“I’ll just sound crazy, right?” he says. “But I think we’ve definitely been a huge part of that change.” Johnson claims that, increasingly, startup launch videos are “very controversial as well, and that’s because they’re trying to copy and paste the method that supposedly works.” Regardless of who started it, this trend is here to stay. From Cluely touting aphrodisiacs in HR packages to Series launching Love Island for growth interns, college tech entrepreneurs are adopting an irreverent social media strategy that meets their Gen–Z peers where they’re at.

In any case, Min is settling well into his role at Cluely. But for what it’s worth, he’s got his own reservations about the company. When it comes to the company’s viral distribution strategy, he wishes they would focus less on metrics.

“People [in San Francisco] are too results oriented,” he says, evidently frustrated by the city’s dearth of visionaries. “For a creative to really flourish, you want to literally tell them there’s no expectations.”

That’s right. In this new market of high controversy and higher stakes, Min is perhaps the only one looking out for the creators. After being inundated with tech buzzwords and conversations about “agentic AIs,” Min decided to host his own party this past July—for creatives only.

“San Francisco is the LEAST creative city I’ve ever lived in,” one of his recent LinkedIn posts reads. “I’m taking a stand to make SF creative again.” To RSVP for Min’s Topgolf social, you had to “NOT be a startup founder” and “NOT be making content exclusively for the sake of growing a startup.”

One day, Min plans to be “the greatest creative in the world.” He continues, “When you think about startup marketing, or how do we build a cool brand … I want people to be like, ‘Oh, look at Daniel’s channel.’” And whether headed for fame or failure, a growing new guard of startups seem to be following Min’s unorthodox advice.

Let’s just hope they lay off the honey packs.