Does photorealism make for a good documentary?

If so, then Cover–Up, the latest film from prolific documentarian Laura Poitras, is a perfect encapsulation of the form. After profiling whistleblower Edward Snowden in Citizenfour and activist Nan Goldin in All the Beauty and the Bloodshed, Poitras now turns her attention to investigative journalist Seymour Hersh. Even at the ripe age of 88, the era–defining reporter is lively and alert, his intensity and drive shining through Poitras’ lens. But though its plotlines are clean and narrative concise, it’s difficult to tell how much affective power to attribute to the documentary itself.

Acting as a highlight reel of Hersh’s long career in journalism, the film ping–pongs between two modes of exposition—direct interviews with Hersh himself and archival footage detailing the horrors his reporting brought into the public consciousness. My Lai, Watergate, Abu Ghraib—images of terror and scandal abound throughout the film, leaving the audience in a perpetual state of shock and stupor. Soldiers coldly recount the way they slaughtered Vietnamese children en masse; photos of Iraqi prisoners being tortured flash across the screen; at points, the film feels like a clip show of atrocities made for the big screen.

An unexpected highlight of the film is Hersh himself, who slots perfectly into the part of the rogue with a heart of gold. Throughout the film, we see Hersh take on the powerful interests that dare to keep the American people in the dark. Towards the tail end of the movie, Hersh barrels into a confrontation with Abe Rosenthal, his own boss at the New York Times, putting his career on the line to take him to task over ethics violations. From the U.S. military to industrial conglomerate Gulf and Western, no Goliath is too large for Hersh's David to bring down. President Nixon sums it up best in a quote from The Oval Office: “the son of a bitch is a son of a bitch, but he’s usually right.”

Seeing Hersh still sharp–witted and active at 88 is a real testament to his personal character as a journalist—but it’s also a reflection of the movie’s somewhat saccharine message that the Fourth Estate must never rest in its pursuit of truth. But for a documentary about a man who dared to take big swings in the pursuit of the next big story, the film itself takes relatively few risks. It feels like any other documentary profile, taking us through Hersh’s life point by point and rarely straying from a matter–of–fact presentation of the late 20th century scandals that Hersh helped break. The story it tells is deeply moving, but the film’s mode of exposition blunts its impact. The historical footage the film presents is mostly left as Poitras found it, leaving it no more capable of moving the audience than a YouTube rip of a film reel. The film feels strangely generic, adding nothing to the stories it tells besides Hersh’s own colorful commentary.

But these aesthetic failures also reveal a deeper problem with the message the film tries to convey. The only connective tissue that holds the film’s isolated cruelties together is Hersh himself, creating a sort of “great man” theory of political change. With no presentation of the underlying political dynamics that allow terror, torture, and tragedy to continue across administrations, the only image the audience is left with is that of the dogged journalist forcing stories into the public consciousness. Gone from center stage are the multitude of activists that fought to make Hersh’s stories into real political change, and even the complex political figures that incisive journalism takes on. Hersh’s own ego is the only thing left to fill that void, warping what could have been a complex story about political and economic power into a stale biopic with an admittedly magnetic central personage.

There’s an argument to be made that the film intends to do nothing more than put horror on display—after all, wouldn’t it do the raw horrors of My Lai and Operation Menu a disservice by daring to speak over them? If that were true, however, the Instagram Reels we see depicting slaughters in Gaza and mass killings in Sudan would have produced political change long ago. Today, we’re all bombarded by an endless stream of images depicting suffering from across the globe—and we don’t do anything about it. The traditional documentary is devalued in the age of “peak content,” its factual depictions reduced to ash by our deficient motivations to actually act on them.

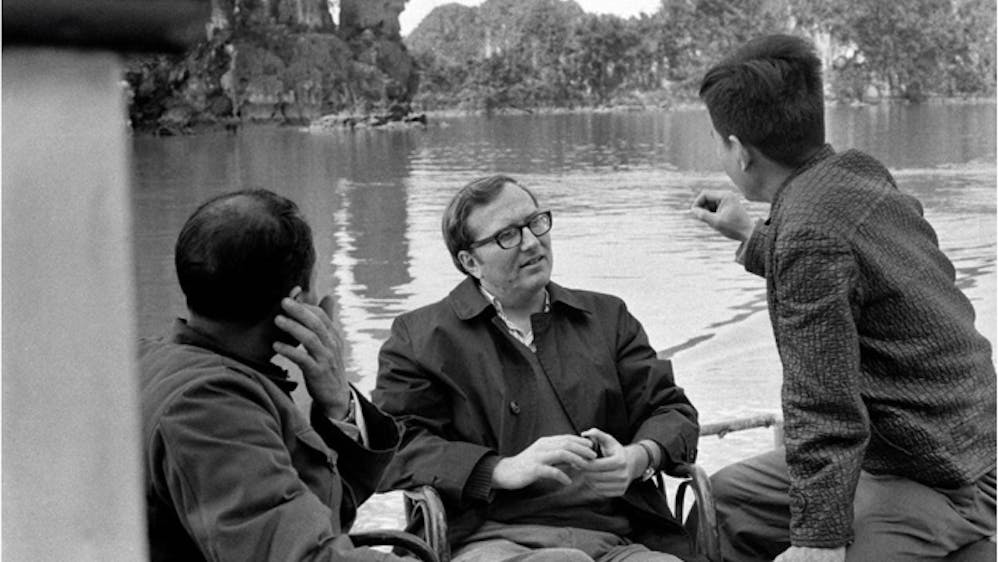

The film does take a few moments to meditate on the enduring importance of Hersh’s political work—interspersed with Hersh’s personal history are clips of him on phone calls with an unidentified source in the Gaza Strip who walks him through maps of troop movements, bullet holes on concrete, bombed–out craters in the middle of busy streets. Even here, however, Cover–Up leaves the viewer largely in the dark, failing to provide the political context that makes these images intelligible. A good documentary must do more than depict the world—it has to force your hand, translating grief into understanding and understanding into action.

The immortal words of Karl Marx may not have been aimed at documentarians, but every filmmaker today ought to hear them: “The philosophers have hitherto only interpreted the world. The point, however, is to change it.”