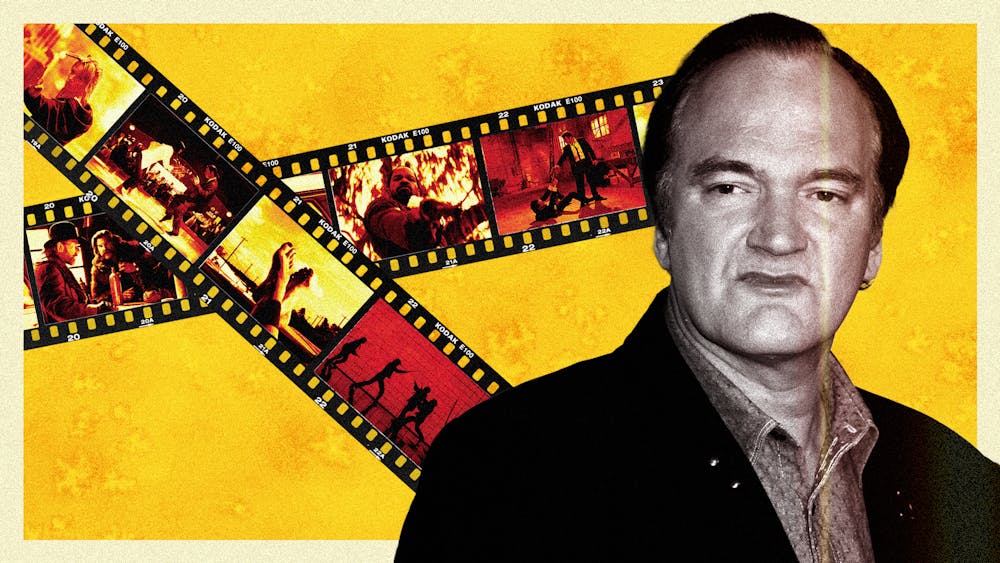

Quentin Tarantino released a new chapter of Kill Bill this month—not as a film, not as a short, but as a Fortnite cinematic. Yes, that Fortnite. The platform built on battle passes, emotes, and endless crossovers is now hosting original work by the filmmaker who once called digital projection “the death of cinema.” It’s hard to imagine a more surreal collision: one of the last self–defined auteurs dropping lore into a game best known for lightsabers, Thanos gloves, and Ariana Grande concerts.

It’s funny. It’s weird. And it raises a real question: what is going on with Tarantino?

For a decade, Tarantino promised a clean exit from filmmaking. Ten movies. No more. That number wasn’t a rumor—it was a self–mythologized endpoint he repeated in interviews, press tours, and retrospectives. His tenth film was supposed to be The Movie Critic, a ‘70s–set drama about a cynical journalist loosely inspired by a real writer Tarantino admired: Jim Sheldon. It was meant to be the capstone. The victory lap. The finale he had spent half his career describing.

In early 2025 interviews, Tarantino said he was “back to square one” and no longer convinced The Movie Critic was the right ending. For a filmmaker who meticulously crafts his own narrative, walking away from the project wasn’t creative drift—it was a crack in the blueprint. When your whole career has been marketed as a perfectly shaped arc, any uncertainty reads like crisis.

And that’s where the pattern starts.

Instead of making the film he spent years teasing, Tarantino released everything but a movie. He expanded Once Upon a Time in Hollywood into a novel and wrote a stage play based on the film. He even penned the screenplay for The Adventures of Cliff Booth—a David Fincher–directed spinoff for Netflix. He has hinted—again and again—at revisiting Kill Bill, a flirtation that resurfaces every few years but never materializes. The work keeps appearing, but it arrives sideways: books, plays, addenda, side quests.

Taken together, it looks like an auteur entering his “expanded universe” era.

The irony is sharp. Tarantino built his reputation on the idea that cinema was sacred. He dismissed Marvel, mocked franchises, and defined himself against IP–driven Hollywood. His career was framed as a perfectly curated shelf of films—a set of ten statements, no more, no less. If any modern director was going to end cleanly, it was him.

But Hollywood no longer believes in endings.

The culture Tarantino built his identity around doesn’t exist anymore. Theatrical windows collapsed. Streaming platforms turned directors into algorithmic inputs. The business that once rewarded singular, auteur careers now treats filmmakers like renewable components in content pipelines. Fortnite—a game—is now a studio, distribution platform, and social network rolled into one. In the world Tarantino stepped into in 1992, you started with shorts and ended with features. In 2025, he is moving in the opposite direction.

It isn’t that Tarantino is broken. It’s that his plan is broken.

The idea of a grand auteur finale only works when the industry supports the infrastructure around it—when you can release a final film that lands like a cultural punctuation mark. But the audience is fragmented. Theaters are weaker. Attention spans are shorter. A tenth film wouldn’t feel like an ending now; it would feel like another tile on a streaming carousel.

So maybe Tarantino is just improvising. He’s jumping mediums. He’s dispersing himself instead of concluding. He’s staying in motion because stopping requires a stability the current industry can’t provide. A novel here, a stage play there, a Fortnite chapter over there—the fragmentation looks chaotic, but it makes sense for someone trying to maintain authorship in a moment designed to flatten it.

There’s also the anxiety of legacy. Tarantino’s generation of filmmakers grew up with the idea that careers formed arcs—debuts, mid–period peaks, elegiac finales. But the business now extends IP indefinitely. Nothing ends, because ending is bad for engagement. That pressure doesn’t sit comfortably with someone who has spent 30 years promising to walk away before decline sets in. The longer he tries to craft a perfect farewell, the harder it becomes to decide what a farewell even looks like.

Which brings us back to Fortnite.

It’s easy to treat the Kill Bill cinematic as a punchline, and in some ways it is. But it’s also a symptom of exactly the forces reshaping his career. Fortnite isn’t a fad. It is one of the most powerful media ecosystems in the world—a platform where millions of people treat narrative, gameplay, and film language interchangeably. For a filmmaker obsessed with the audience, it makes a strange kind of sense to drop a new chapter of his mythology in the most culturally dominant venue available.

It also reflects a truth Tarantino has been publicly dancing around: the audience for traditional theatrical cinema is shrinking, and the places where cultural conversation happens have moved elsewhere. If you still want your work to reverberate, you go where the audience already is—even if that place looks nothing like a movie theater.

The result is a career that seems restless, scattered, and occasionally contradictory. Tarantino says he wants to retire. His behavior suggests the opposite. He announces a final film, then abandons it. He expands old work instead of creating new work. He moves from prestige formats to a platform whose most famous narrative contribution is a man in a banana suit (or is it a man–sized banana?) firing an assault rifle. It’s all bewildering until you accept the premise: the framework he designed his identity around no longer applies.

Tarantino isn’t malfunctioning. He’s adapting—awkwardly, unpredictably, sometimes hilariously—to a culture that refuses to let anything end.

And maybe that’s the point. In a landscape where studios resurrect franchises endlessly and platforms stretch stories across every medium imaginable, Tarantino’s struggle to finish his career isn’t a personal failing. It’s a sign that the era of clean artistic endings is over. Movies don’t conclude anymore—careers don’t either. Everything keeps generating, mutating, expanding—even the work of a director who once tried to build a filmography like a sealed museum exhibit.

Tarantino didn’t break—but his finale did. And now we’re watching him try to write a new one, one Fortnite short at a time.