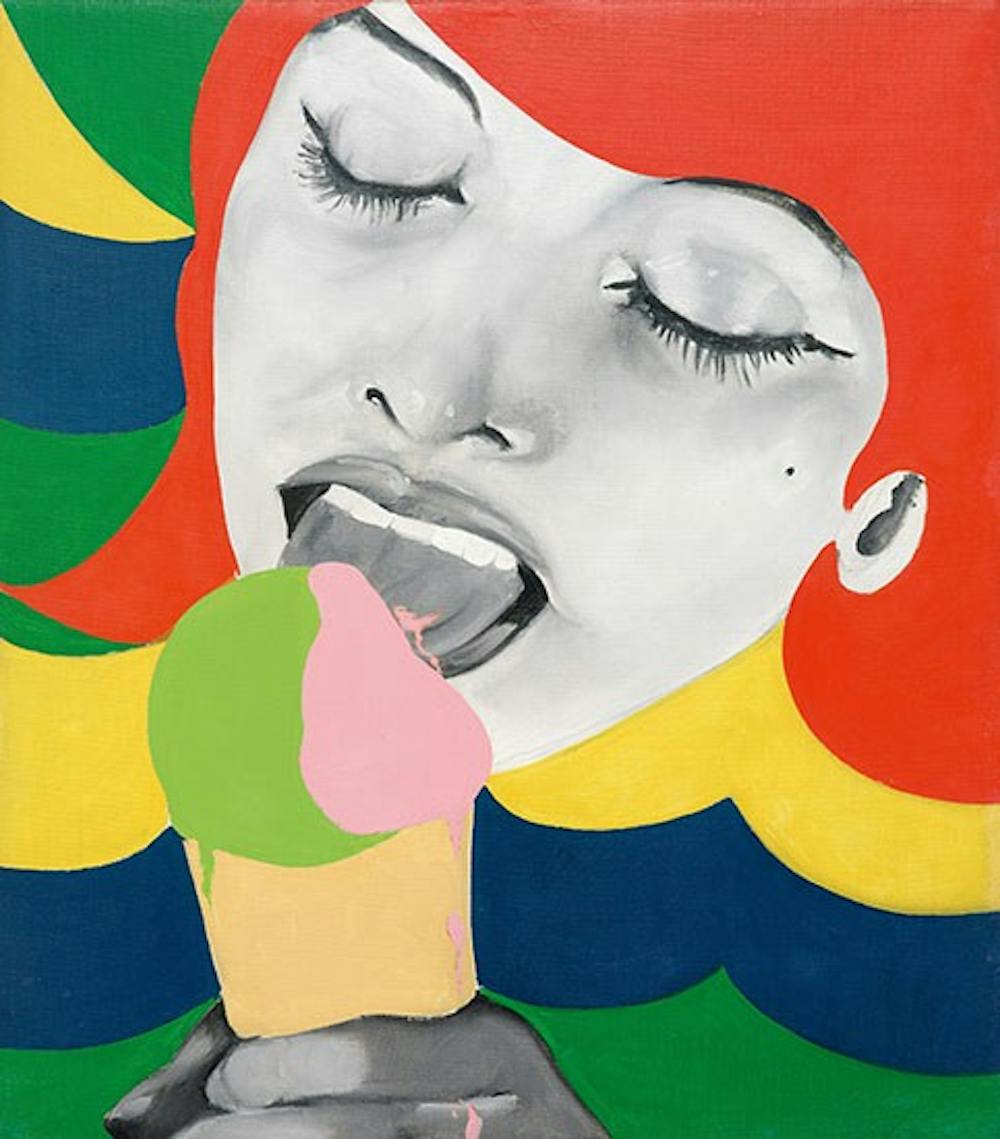

Before I visited the International Pop exhibition at the PMA, I had only seen the painting "Ice Cream" by Evelyn Axell (1964) on the cover of the band Lucius’ 2014 album “Wildewoman.” I had no idea it was a famous work of art from Belgium. I just thought it was a graphic that looked slightly like the two identical lead singers.

Jess Wolfe and Holly Laessig started Lucius after bonding in college over the realization that there should be a female version of the Beatles’ "White Album." Because of the '60s inspiration for their music and appearance, it makes sense that the artists chose Axell’s colorful oil on canvas painting to represent their first LP. The International Pop exhibition, which opened in February and will close on May 15th, aims to do the same thing with visual art that Lucius communicates with music. It proves that the Pop movement, which took the world by storm in the mid–20th century, wasn’t only limited to male artists depicting national consumption and sexualization—and it wasn’t dominated by American artists, either.

At Penn, we’re all (maybe too) familiar with Pop art, whether we think about its origins or cultural impact at all (do Claes Oldenburg’s Split Button or Robert Indiana’s LOVE sculpture ring any bells?). We most certainly have seen Andy Warhol’s Campbell’s Soup cans, and likely would recognize Roy Lichtenstein’s comics. However, if presented with Ushio Shinohara's Japanese soda sculptures, we might not have a clue. Pop art gained a following at the same time in Latin America, Japan and both Western and Eastern Europe. How can we consider ourselves educated college students if the only popular art we know of comes from less than half of the globe?

All of the work on display for International Pop was made between the years 1956–1972, but the time frame is its only limitation. The show conveys that Pop art comes in a wide variety of forms, including painting, print, collage, sculpture, installation and film. The exhibit even showcases Vogue magazine and a golden ear (to be fashionably worn on top of your real ear) as essential pieces of the Pop trend. The 150 works have in common the primary and acid colors popularized by advertisements and the same motives to draw inspiration from external stimuli. The key difference between American/British Pop art and South American and Asian Pop art is that this stimulus was largely communist propaganda.

On one wall, red panels are covered by black sheets attached to a string that you can pull open and close, symbolizing the risk of censorship and exposure for Eastern artists. In the same room are Brazilian cartoon–like images of rocket launches, and from the ceiling, Jesus Christ hangs crucified to a US Air Force jet. The exhibit explains that artists from Brazil, Argentina, Italy and Japan were wary of US influences, and so rejected the Americanized term "Pop Art" at first.

The global perspective on “well–known” creative eras is going to be a trend going forward in the curated world, as an investigation of the history we’ve erased by having a predominantly Western focus. Obama's visit to Cuba this past week in the hopes of building commercial and political ties proves that America is not the center of the world today, and it wasn’t in the 1960s and '70s either. Pop Art wasn’t just about Jasper Johns’ images of the American Flag or Andy Warhol’s silkscreens of Coca Cola and Jackie Kennedy—it spoke to how mass media affected ideas in every country, even those on the front lines of World War II.

(Photo courtesy of www.philamuseum.org)