The relationship between the literary and the visual is not like a couple holding hands, where the palm is the singular point of intersection; it’s more like an embrace, where complicated bodies meet infinitely, and the hand that appears to be of one person, belongs, instead, to another. In Professor Charles Bernstein’s course, “Experimental Writing,” students explored this relationship through hands–on, experiment–based work.

One of his students, Jacob Faber–Rico (E ’20), said the main goal of the class "wasn’t to produce great poems; it was to produce different poems.” To inspire this, students responded to a list of experiential prompts, generated by Bernstein, to create new material. Though the objective may not have been to produce the next The Sun and Her Flowers (though the quality of this is open to interpretation), there is no denying that there is a correlation between fresh aesthetic takes on poetry and success, as can be seen in the students' final products.

The presentation of visual art inspired students' creativity, encouraging them to adopt new perspectives. For one exercise, students went to the Philadelphia Museum of Art (PMA) and wrote poetry based on one of the works. Jacob chose Marcel Duchamp’s The Bride Stripped Bare by Her Bachelors, Even. The piece involves two panes of glass and appears in the museum in front of a window, so that the observer can see through the art to the museum and the outside world. “So I tried to write my poem at two different levels,” says Jacob, “Like on one, about the artwork but more so about the environment of the artwork and the people around it and the room around it.”

The resulting poem was a product of crossing the boundaries between the visual and the literary. As Jacob puts it, “boundaries between a lot of fields are really much, much blurrier than they are made out to be.”

This sentiment is shared among his classmates, who come from backgrounds in engineering, science, nursing, and English, among other majors. Justin Swirbul (E ‘20), for example, connects poetry and computer science. “I wrote a couple poems in code,” says Justin. “It’s more than just writing, I think. It’s kind of the whole creative process, just playing with things that exist already.”

For Justin, the “whole creative process” entailed hours of work, although he recognizes that the course is very flexible. Students decide which exercises to respond to and how much time they will put into their projects.

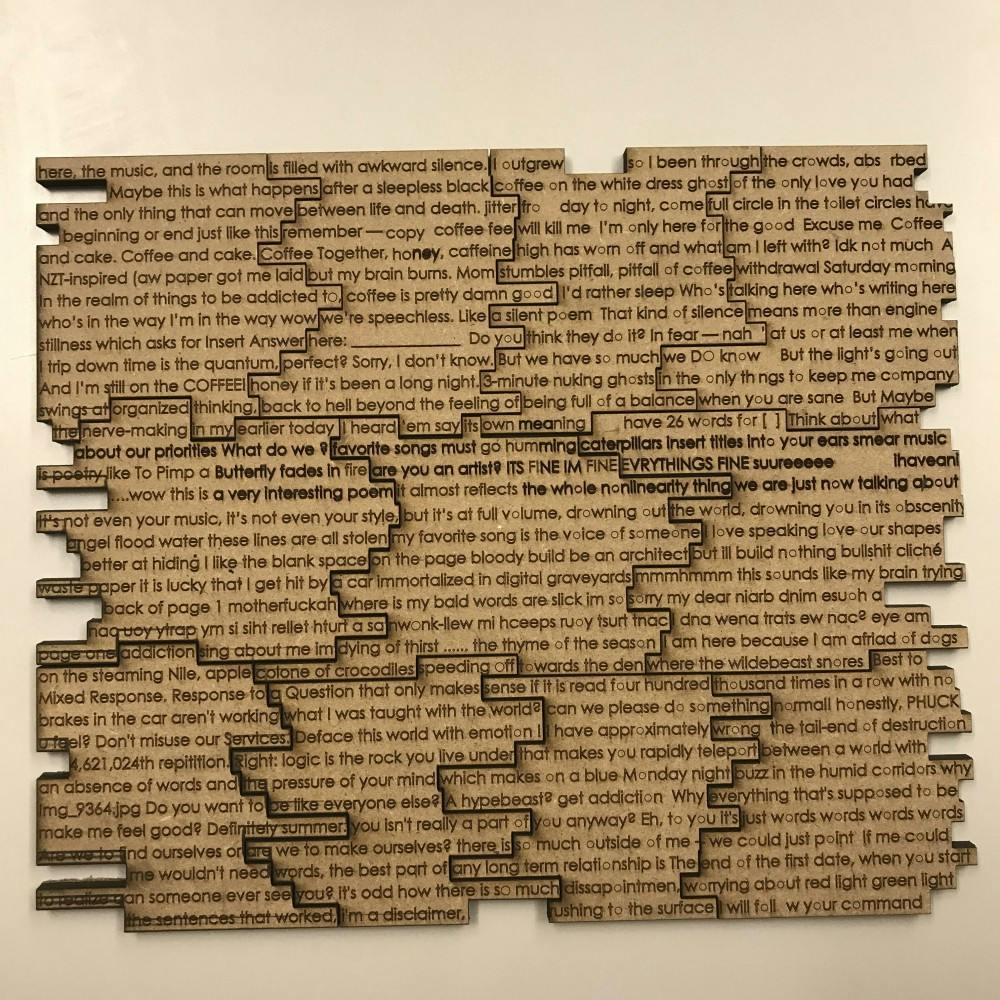

Every semester, Justin chooses a new arts related course at Penn at random to be his creative outlet. During the chaos of finals season, he could be found at the laser cutter, reworking his tangible poem which was created out of class collaborations rewritten using erasure. “So then each person got like a different chunk of the whole poem. And I cut it in a way that each poem can be read individually–it don’t make much sense but not a lot that we did made sense,” he says.

Even so, this style of poetry does not lose what so often defines poetry—sentimentality. For Kelly Liu (C ‘21), her final project reflected the degree of vulnerability she had allowed herself through the course by way of writing from her stream of consciousness. To accompany the words, Kelly made nearly a dozen origami cauliflowers, one for each student. The positive environment Professor Bernstein created fostered that transparency and openness. “It’s such a collaborative environment,” says Kelly, “But Charles is super funny, and he’s super relaxed, and he just makes us care about the material. And I think as the semester went on, we became pretty good friends with one another, not in the sense like we hang out outside of class, but just cause we see each other's writing, we understand each other a little more.”

Courtesy of Kelly Liu

Kelly Liu's cauliflower sculpture, shaped to represent the first line of the poem.

Though the class is being retired from the department, the very idea of it is not yet lost. Jacob recalls Professor Bernstein often saying, “The only thing that matters is what’s interesting.” One of Bernstein’s oldest tips was: “Read things backwards.” "Experimental Writing" may have been a course about combining the visual and the literary in order to see things from a different perspective, but we could learn from experimenting with creativity.