“I see another tourist

put their arm around that

forsaken statue—soiled

And all I can think of is

‘Oh no’

— Rupi Kaur”

Recognize the poem? It’s from Penn’s Official Unofficial Penn Squirrel Catching Club, not the acclaimed Milk and Honey that has been the subject of many an Instagram post (too many, I must add). But at first glance, from its style and form, this verse could easily be mistaken for any one of Kaur’s poems. And it’s no exception — since her first book Milk and Honey was released, thousands of imitative poems have spread across the Internet. They’ve become almost an integral aspect of popular culture (that is, if memes fall under the category of popular culture).

But why? What’s the deal with Kaur? If any college student can write a poem arguably rivaling those by Kaur on a meme page of all things, why is she so famous?

It’s because of what I would call the “revolution.” The digital revolution, I mean — the integration of poetry into the world wide web. Arguably, this is the most important part of Kaur and her work: her accessibility. Of course, this is not to discount the content of her poems; her stories read of both traditional poetic topics— love and heartbreak —and more “millennial” topics— race, nationality, and the strengths and struggles of womanhood. In print, her short poems and black–and–white illustrations are sporadically interrupted by photos of Kaur, who carries with her an aura of romanticism, femininity, and a oneness with nature. Just by the content alone, her stories are what make her work so relatable to an audience of several million.

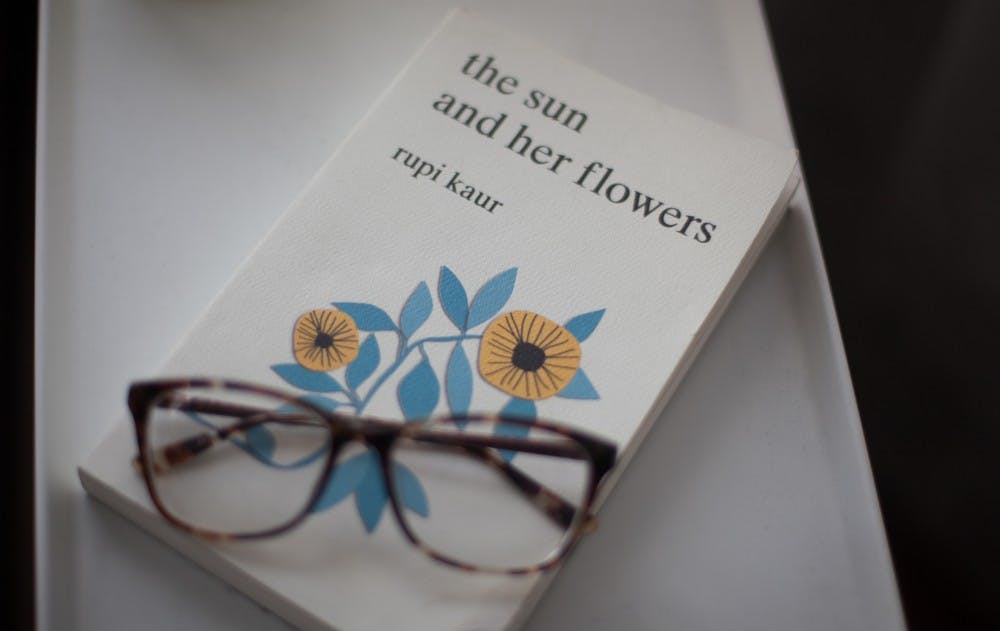

All this works in conjunction with her popularity over the Internet. A New York Times best–selling poet and artist, Kaur has gained international recognition for her verse and her online personality. Beyond her two books (Milk and Honey and The Sun and Her Flowers), she maintains a constant interaction with her fanbase over social media. It’s allowed her to move from Amazon's self–publishing platform to the glossy white shelves of Urban Outfitters.

At the same time, though her accessibility and simplistic form has drawn so many, they are also precisely what have brought on sharp criticism and ridicule. Just earlier this month, critic Rebecca Watts described Kaur (along with her fellow Internet poets and her cult following) as tainting the definition of literature, timeless in its craft if not its subject. The short form media made solely for a technological age goes against the idea that poetry has “the best chance of escaping social media’s dumbing effects; its project, after all, has typically been to rid language of cliche. Yet in the redefinition of poetry as ‘short–form communication,’ the floodgates have been opened.” And she’s not necessarily wrong— the flood of memes dedicated to parodying Kaur’s poems is a testament to how poetry has since been denigrated through social media.

Another criticism is that Kaur claims to represent both the female and the Asian community, citing her birth as a defiance of female feticide. Surely, within the literary field, she’s pushed past the glass and bamboo ceilings, and there is credit to be given for that. But how that translates into her poetry is another issue. There’s no way to ascertain how her short–form communication, most of which has become the subject of jokes, can adequately explore the nuances of the issues she claims to tackle and give credibility to the seriousness of the matters. To discover how other poets tackle these issues, Kaur’s readership should familiarize themselves with other important works on these fronts. If you are interested in Asian feminist poetry that reinvents form and uses translation, why not try I Am the Beggar of the World: Landays from Contemporary Afghanistan or Songs for Love and War: Afghan Women's Poetry?

I, for one, stand firmly with her critics. Nevertheless, the value in Kaur’s work for me is that it has made poetry more accessible, and by way of that, has made literary criticism more accessible. Those who read Kaur will likely encounter those who critique her work and familiarize themselves with conventions and definitions of literature. Kaur is a gateway to poetry, but she hardly stands inside those gates.

At the end of the day, fans of Kaur have discovered a way to popularize poetry. Hopefully, the popularity of real craft will follow.