When I arrived in Cape Town for my semester study abroad in late January, I was delirious. I had just spent 36 hours in airplanes and airports, and I was limping through the delightful cocktail of sleep deprivation and my anti–anxiety flight medication. All I could do in this state was observe, wide–eyed. And there was plenty to look at in the customs line alone. Signs everywhere told travelers:

“Limit your intake to 50 Liters a Day!”

“Showers MUST Remain Under 90 Seconds”

“122 Days Until Day Zero”

On my way to my dorm in Rondebosch, a wealthy Cape Town neighborhood, I struck up a conversation with the taxi driver. The highway from Cape Town’s airport to Rondebosch took us past some of the city’s most impoverished townships, and he identified them one by one. These townships, legacies of Apartheid’s forced resettlement of non–whites to the outskirts of the city, are underdeveloped and under–serviced. My taxi driver grew up in one in the city center, he says. It’s named Langa, and he pointed it out as we drove past.

If “Day Zero” was a reality—he wasn’t convinced of it—townships like Langa would see lines of people seeking their daily water ration in the early morning hours. The water crisis had been tough on his family, but not impossible. He and his kids had switched to bucket and sponge showers to conserve.

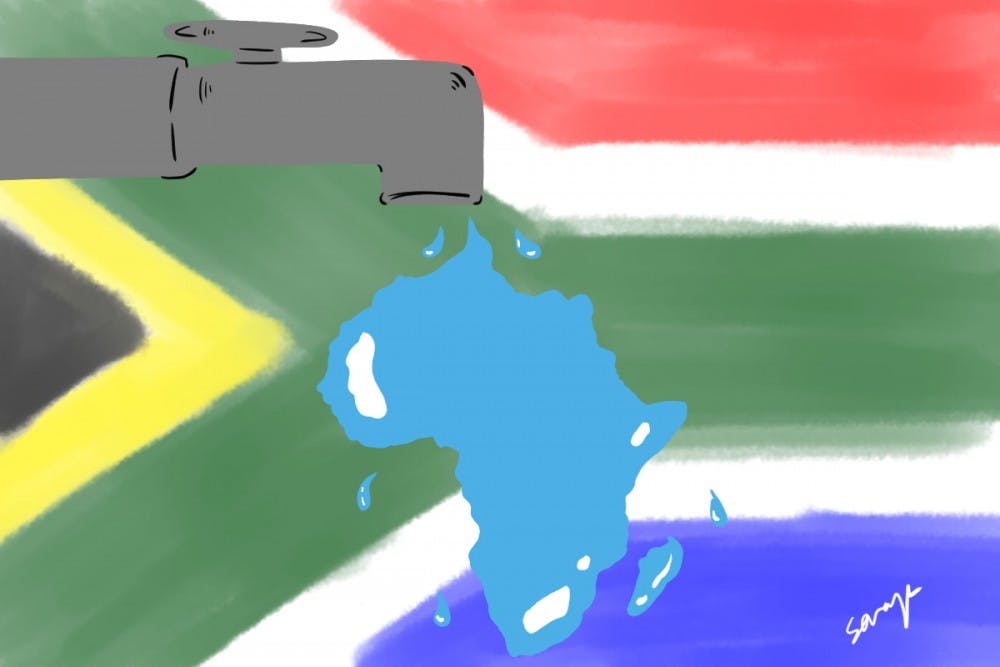

Oh, I thought, they aren’t fucking around. I knew, of course, about Cape Town’s historically unparalleled three–year drought and subsequent water crisis before arriving. I knew it was the first major city to likely run out of water as a result of climate change.

My American and South African study abroad institutions reassured me of my safety. The crisis was serious, they told me, but there was no reason for foreigners to stop traveling to Cape Town. It wouldn’t really impact my experience here. I received a flurry of comforting emails from my program, which I forwarded to my paranoid family members. They promised that if the taps ran out, they would resource water privately. It would be fine. So, on the first day of my semester abroad, clutching my bags on that rickety taxi ride through the city, I wondered what reality I would be living for the next five months.

Every day after class, I hike down the hilly base of the University of Cape Town’s campus towards my dormitory, a residence of one hundred or so exclusively American study abroad students. There, I know massive jugs of clean, cool water will be waiting for me. They’re refilled daily. Signs in the bathroom gently remind me that showers should be reduced to two minutes. I should try to turn off the tap while brushing my teeth. If it’s yellow leave it mellow. Et cetera.

Within my little compound of American, elite institution–backed privilege, there is no culture of conservation. Day Zero will not come for us. Nor will it come for the scores of tourists still flocking to this hyper–instagrammable city, staying in hotels or airbnbs that openly promote their unaltered water access.

The same cannot be said of Cape Town’s permanent residents, especially those outside the wealthiest classes. Restrictions are their reality. Capetonians already face fines for exceeding their daily water ration, penalties not once mentioned to the American students in my program. Day Zero is coming for them.

For some, it’s more than a matter of restrictions. It’s even more than an impending Day Zero, be it one week or four months from now. Cape Town's most systematically disadvantaged have at no point had access to clean, reliable drinking water. Meanwhile, one hundred or so of my predominantly white American cohorts sheepishly take their fifteen minute showers, with only the slightest bit of shame.

Early on in my time here, I attended a roundtable discussion by some of the student leaders of #RhodesMustFall and #FeesMustFall, two prominent South African protest movements. They aim to decolonize the universities and make them more accessible to low income students, respectively.

A well–intentioned American student inquired about the life of non–white Capetonians during the water crisis. How were the residents townships surviving the water crisis? What about people living in informal settlements? How would they survive Day Zero?

One of the panelists laughed, and replied. It has always been Day Zero for black South Africans.

The line stuck with me. I jotted it down. His laughter was the miles disconnect and tension between his life and the life of the questioner. The miles between my life and the lives of those who live in townships like Langa, Gugulethu, and Khayelitsha.

My institutional wealth and privilege allow me to travel to this exceptionally beautiful city and not feel one ounce of the suffering that is the norm for so many of its residents. Obviously, I am grateful for this privilege. I’d be a hypocrite to say otherwise. I haven’t abandoned the safety and hygiene that my dormitory promises. I don’t plan to. But I also cannot stop thinking about my advantage in this moment of crisis. A few months ago, I had no conception of the extent to which living here would shake my thoughts and practices surrounding water, and by extension, life itself. When access to such a universally needed resource is in jeopardy, it amplifies the effects of any kind of systematic injustice.

At present, I am safe. I have access to water. And, thanks to significant cuts in consumption by permanent residents of the city, so is Cape Town. City officials recently pushed “Day Zero” to early July. This does not negate the fact that the city is a few mismanaged months from absolute crisis and heightened suffering for Cape Town’s least advantaged. This is especially true if the rainy season (the Southern Hemisphere’s winter) yields less than expected rainfall.

Regardless, I am so grateful to be in Cape Town, but my reverence for this experience is complicated. It is laced with the guilt that comes with increased familiarity of my advantage in this life. It is laced with increased familiarity with the suffering of others. It’s allowed me to feel truths in Cape Town that I hope to bear witness to in Philly upon my return. Living here has forced me to reflect and analyze and think in ways I never have. And for that, I am overflowing with gratitude.

Got a story tell! Pitch it below!