Remember when Hannah Baker told Zach that 2001: A Space Odyssey was “boring…You should definitely see it so that when pretentious people talk about it you can yawn really loudly,” in season 2 of 13 Reasons Why? Yeah, me neither. I’ve never even seen the show. I have seen 2001: A Space Odyssey though, once, this past weekend in the Franklin Institute’s massive dome theater.

2001: A Space Odyssey was released in 1968, 103 years after the publication of Jules Verne’s From the Earth to the Moon, 46 years before the release of Alex Garland’s Ex Machina, and 50 years before 2018. In the five decades viewers have had to digest the nearly–three–hour film, 2001 has been hailed as a masterpiece, the “Ultimate Trip,” and a boring, pretentious film to be yawned at. Having watched it for the first time half a century after its initial release, I think that it’s all of the above.

2001 stems from the ever–changing nature of science fiction. Since Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein revolutionized science fiction in the 19th century by being one of the first pieces of literature to question the lengths to which science could, or should, evolve, successive science fiction revolutionaries and their works have tackled similar ideas. Jules Verne, who reached success in sci–fi half a decade after the publication of Frankenstein, thrived on an excited exploration of where science of the mid–to–late 19th century could take us—including getting to the moon using gunpowder and a cannon. Verne's contemporaries challenged his vision of optimistic scientific development with less confidence in humankind's ability to control the newly—discovered powers that come with such development. H.G. Wells' work most famously represents this contrast to Verne's.

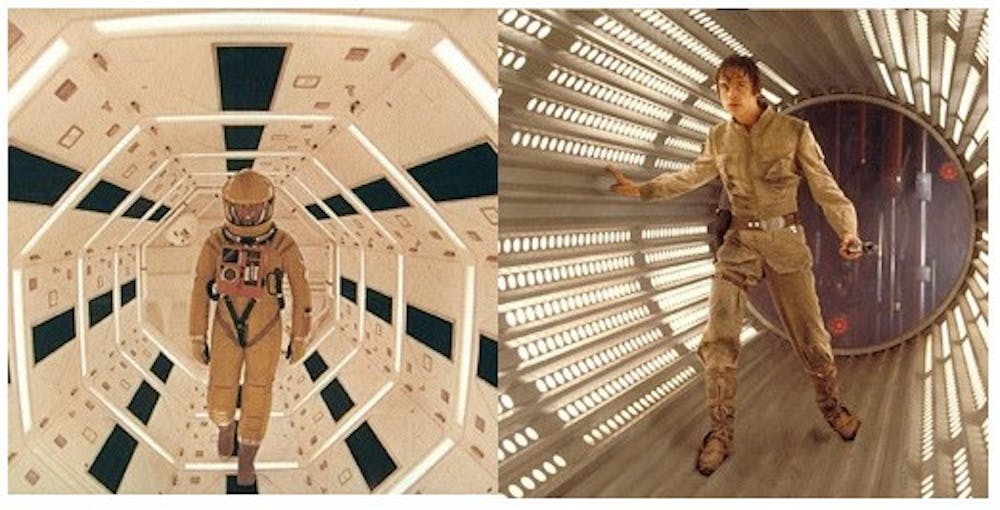

The 20th century saw this same sci–fi dynamic, but with Star Trek and 2001. Star Trek began airing in 1966, spreading a vision of a hopeful future in which science has brought otherworldly benefits to the human race. 2001 was released two years later, offering to the public a depiction of alien–induced solitary death in space and terrifying human–like AI in contrast to Star Trek’s peaceful planet–to–planet trade system. 2001 is special like how Frankenstein and The War of the Worlds are special: it is the first work of its time to so accurately address fears and moral limits of STEM advancement in a body of media that it is regarded as a cautionary what–if tale that created—and continues to create—conversation in professional and public bubbles. The pattern of optimistic sci–fi being released simultaneously with despairing, horror–like sci–fi continues to flood the genre even today (check out Her (2013) versus Ex Machina (2014)).

50 years after 2001 was first shown, I was both amused and impressed by the movie’s depictions of FaceTime (picturephones) and chunky laptops, both, but particularly the latter, being impressive feats of their time. The same can be said about the various drawn–out sequences scattered throughout the film that simply showcase spacecraft: what kind of imagery would this be, not to us today, but to an audience that had not yet even experienced man’s first landing on the moon? The ultimate trip it must have been. And it still is, even despite our constant exposure to technology, ranging from annually–revamped iPhones to massive, publicly–announced NASA missions. The simple design of the monolith has allowed it to age gracefully and continue to confuse audiences today. The colorful, infinite ending sequence that Dave sees before aging rapidly is still hypnotic and oddly beautiful. The endless scene of Dave retrieving the malfunctioning antenna control device, complete with a soundtrack of only Dave’s calm breathing, is universally mind–numbing and allows the viewer to trip out themselves in an effort to stay awake.

Impossible as it may be, if I were to describe 2001 in a single sentence, it’d go something like this: to achieve enlightenment, humanity must suffer first through human error and the endless expanse of time, and then suffer again in trying to decipher what the hell Kubrick meant. I would argue, though, that not all suffering is bad.

In celebration of the film’s 50th anniversary, 2001: A Space Odyssey will be playing at the Franklin Institute in 15/70mm IMAX format through November 25.