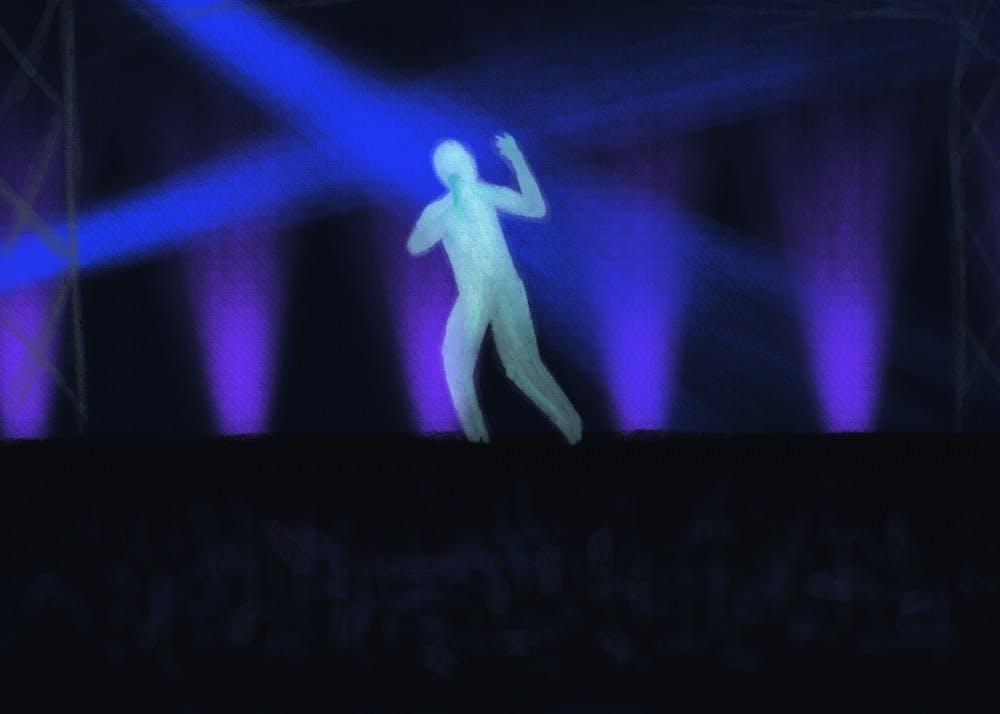

Recently, it was announced that Roy Orbison and Buddy Holly holograms would be joining one another on stage for a touring show, the “Rock and Roll Dream Tour.” This will be the Orbison hologram’s second tour; the estate–approved image was recently the subject of a touring performance, "In Dreams", this past fall. Like the late Frank Zappa’s hologram, an actual band accompanied Orbison’s hologram on stage to supplement the “newly recorded, never–before–heard, digitally remastered arrangements of his classics.”

Since Tupac Shakur first appeared on stage with Dr. Dre and Snoop Dogg at the 2012 Coachella Valley Music and Arts Festival, several holograms of deceased performers such as Amy Winehouse, Zappa, and Maria Callas have been developed.

It’s all nothing but a money grab. Take the Amy Winehouse hologram, for instance: Since her death in 2011, her catalogue has sold the equivalent of 301,000 music units, according to Nielsen. To music executives, of course, this huge number of sales indicates an interest in the singer that must be capitalized upon, and with the availability of holographic technologies, why not stage a tour? After all, nostalgia is a gripping force that people love to lean into.

All it takes is the licensing of her master recordings from her record label as well as the rights to her likeness and image, controlled by her estate. A production team writes the script for her hologram, it’s put on stage, and sentimental fans are satiated as her likeness woos them into their memories. Plus, everyone’s pockets get lined along the way. Everyone wins, right?

Everyone except for the deceased artists. Art, music, and performance are a personal expression of the individuals who create them. Thus, there’s an inseparable humanity to these works. Especially with live performances, a musician can interact with an audience, feed off their energy, and edit their sets according to what they are feeling in the moment.

Holograms ignore these creative freedoms and reduce an artist’s image to a stale derivative of past performances. The performers are being grave–robbed of their agency by the writers and producers of these shows who are essentially co–opting their narrative and building upon their legacy with the use of their image.

At the time of their deaths, there’s no way Holly or Orbison could foresee the availability of holographic technology for posthumous concerts, so it would’ve been possible to amend their wills in such a way that could’ve controlled for. Naturally then, the decision falls upon their estates.

Both Orbison’s son and Buddy Holly’s wife have separately expressed approval for the joint hologram tour saying the two musicians enjoyed collaboration and shared a mutual respect for one another. A familial stamp of approval seems to legitimize the use of their holograms, and it feels right that the tour’s royalties will most likely benefit family members in the respective estates. Still, the question must be raised as to whether anyone, even family, has the right to profit from the image of a deceased star, let alone put them back on stage.

Though the legitimate enjoyment by fans of the tour should not be discounted entirely, the inherent problems with holographic performances cannot be ignored. These performances are far different from, say, watching a televised past performance of musician. At least in the case of the latter, the image exactly replicates something that actually happened. Writers constructing a performance using the likeness of a performer as a character, feels like using dead artists as puppets, which is disrespectful, to say the least.