For most of us, punitive justice is all we know. From the moment we enter the school system as children, we’re exposed to multiple forms of punishment—facing suspension for breaking the dress code, or being isolated in 'time out zones' when we’re being too disruptive in class. The reliance on punishment as the primary response to harm is engrained into our social structures, from prisons and schools to our own family networks. As author and activist adrienne maree brown indicates, when we cause harm, the knee–jerk reaction is often to remove us from our community in some way.

Punitive justice describes the United States’ criminal legal system, an institution that is supposed to promote safety and accountability, but has devastatingly and violently harmed marginalized communities. On April 11, 20–year–old Daunte Wright was killed by police just ten miles away from where officer Derek Chauvin stood on trial for the murder of George Floyd. Immigration and Customs Enforcement continues to deport and jail immigrants at record numbers. And throughout, the U.S maintains the highest incarceration rate of any other country in the world, increasing the number of people in our jails and prisons by 500% in the last 40 years.

Restorative justice seeks to break this cycle. At its core, it's a process rooted in aboriginal and Native American communities from North America and New Zealand, which rely on community circles to resolve conflict and harm. Restorative justice practices are often used today to address specific instances of interpersonal harm, while another distinct process, transformative justice, goes further to interrogate the social conditions that allowed the harm to happen in the first place. Transformative justice works to center the victim's safety and needs, cultivates accountability without a reliance on the state, and, crucially, addresses the root causes of harm so that it doesn’t happen again. Both practices are community–based solutions that reject the violent and retributive methods of the criminal legal system.

Writer Mia Mingus articulates that transformative justice is an abolitionist framework that goes beyond the absence of state institutions like prisons and police—it is “putting in place things we want, such as healthy relationships, good communication skills, skills to de–escalate active or 'live' harm and violence in the moment, learning how to express our anger in ways that are not destructive, incorporating healing into our everyday lives.”

The Philadelphia community in particular has made many strides in the direction of restorative justice. In the first attempt on a city level, Philadelphia initiated a restorative justice model that could shield hundreds of protesters from prosecution. During the protests following the killings of George Floyd and Walter Wallace Jr., over 500 protesters were arrested and charged by the city. According to the district attorney’s (DA) charging unit supervisor, nearly all of the arrested individuals were qualified for public defenders, and many were so impoverished that they would not be able to pay restitution. In 80% of these cases, the DA is offering a program called Civil Unrest Restorative Response, which would drop the charges and expunge the records of those who successfully complete the program, many of whom had no prior arrests.

The program’s education sessions will be run by Rev. Donna Jones of the Metropolitan Christian Council of Philadelphia, an organization that has been facilitating a community–based restorative justice network called the Restorative Cities Initiative. Specifically the protesters who choose to opt into the program will join restorative circles alongside businesspeople and community members to voice and listen to the harms that others have experienced and what steps can be taken to properly address it. Those who don't opt into the program will be obligated to complete community service.

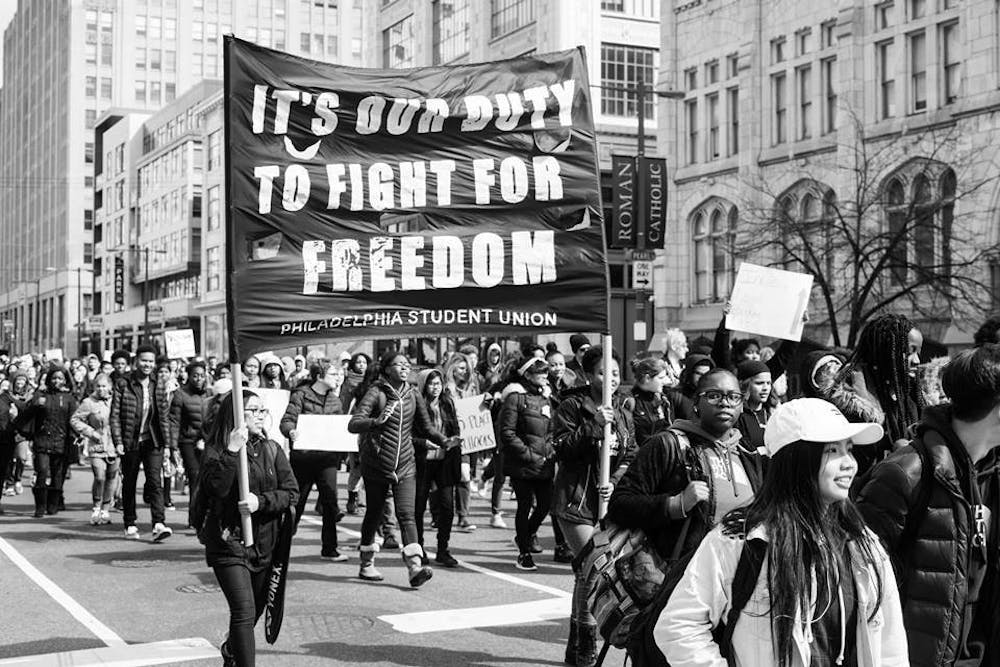

While the Civil Unrest Restorative Response is an unprecedented legal initiative, organizers in Philadelphia have long worked to establish restorative justice practices in their neighborhoods. Jones and the Metropolitan Christian Council of Philadelphia have been offering a variety of free restorative justice trainings for community stakeholders, such as neighbors, block captains, and clergy, throughout the year. And nearly three years ago, youth leaders in the Philadelphia Student Union and T.U.F.F. Girls, an activism–driven leadership program, outlined a list of demands, including the city’s divestment from school police officers and the expansion of restorative justice practices and programs in Philadelphia schools.

Last summer, Penn graduates Hyungtae Kim, Kwaku Owusu, and Mckayla Warwick created an organization called Collective Climb to foster healing, leadership, and group conversations to process current events for youth in West Philadelphia. In response to the months of protests against police brutality and violence, Collective Climb pivoted from their initial focus on financial literacy to restorative justice, which, according Warwick, “represent[s] the core of what Collective Climb really wants to touch on, and that is a conversation around liberation.” In addition to their Collective Kickbacks which touch on a variety of discussion topics ranging from “radical Black joy to interpersonal vulnerability,” the organization has also facilitated the Restorative Community Project for eight youth organizers. Over the course of six months, the cohort will co–conduct original research, become trained as restorative circle–keepers, and present an original lesson for the next cohort of the project.

The organizing labor of Philadelphia activists have made the vision of justice, accountability, and healing outside the punitive carceral system a reality. As writer Wendy Ortiz explains, restorative justice ultimately contains the fundamental belief that “repair is possible.”