Many things in life can be solved with formulas—like a calculus problem or the optimal fantasy football lineup. But not love. Especially not in the City of Brotherly Love.

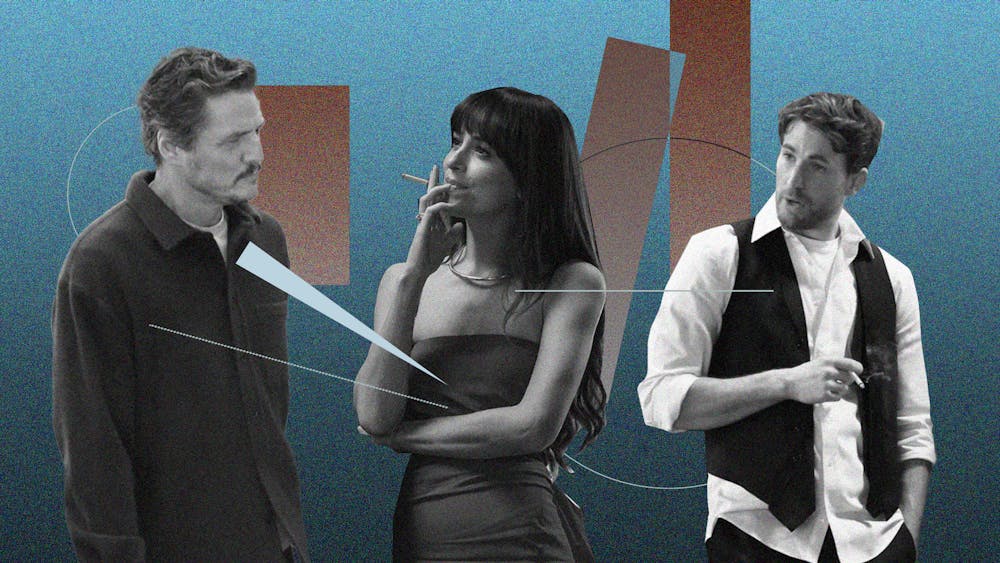

The latest release of Materialists foregrounds the quantitative nature of modern love—laundry lists of requirements, meal transactions, and emotional calculations. The film follows Lucy, a New York matchmaker, portrayed by Dakota Johnson and inspired by writer and director Celine Song’s own experiences as a matchmaker. Lucy chases perfect matches as much as she chases love in her own life, which arrives imperfectly—in the form of John, her ex–boyfriend. John—played by Chris Evans—doesn’t check any of her boxes: He’s half–jobless (an aspiring actor), broke, and the kind of partner that her gamified approach to love would filter out.

Yet even after watching the movie, a question persisted: What even is matchmaking? Does that even exist in Philadelphia, or at Penn, and is it just like how it’s portrayed in Materialists?

That’s a question that Lauren Daddis—a Philadelphia–based matchmaker for Three Day Rule, a matchmaking company—can answer.

While Materialists is deeply entrenched in the fast–moving, often faceless sprawl of New York, Daddis’ world is slightly less cinematic (though no less interesting). Daddis notes that Philadelphia is a place where “everybody knows everybody,” especially through networks established by institutions like Drexel University, Penn, and Temple University, which attract hordes of students and staff. With so many college students in the city, most eligible bachelors and bachelorettes already know each other, or know someone who knows someone they’ve dated. “When people go to swipe on apps, they’re just getting burnt out and seeing the same 30 people,” Daddis emphasizes.

In fact, it is the bubble–like nature of Philadelphia that Daddis capitalizes on. Many of Daddis’ clients come to her seeking the privacy that Three Day Rule offers them, which is an alternative to the visibility and overlap that comes with dating apps. “They don’t want to be on the apps,” Daddis explains. “They don’t want to see people they know, see people they’re in class with. Even professors, they don’t want to see their students.”

One of the darker plotlines in Materialists is centered around Sophie, one of Lucy’s clients, who is assaulted by Mark—one of her other clients. After Lucy finds out about the assault, she breaks down and ravages through her notes on Mark in search of red flags that she may have missed. However, she isn’t able to scavenge anything substantial from her notes that would’ve informed her about Mark’s behavior. When asked about how she felt about the scene, Daddis says that it doesn’t reflect how she approaches her work and even made her “a little mad,” as Lucy had only written very superficial things—related to money and height—about Mark in her notes. “That was upsetting, because I was like, you didn’t do your job,” Daddis says. “I like to think that we go much deeper than that. To really find, a partner for someone, it needs to be more than [that].”

At Three Day Rule, the matchmaking process is certainly deep, and much more intricate than a swipe–based app. Once a matchmaker is hired, they spend time getting to know the quirks and traits of their clients and understanding their clients’ preference in a partner; they figure out their clients’ non–negotiables while probing at other boxes that the client might want checked off. Then, the matchmaker begins interviewing as many people as they can on behalf of the client—whether it’s the clients of other matchmakers, former clients, or people who’ve signed up to be in Three Day Rule’s network without formally hiring a matchmaker.

Daddis always schedules video calls with potential matches for her clients instead of relying solely on written profiles or phone calls. “I think it’s really important to see the body language, the eye contact, and how they answer questions,” Daddis explains. “People can do great with their voice, but if their shoulders are up to their ears and you can see they’re stressed out, or they’re lying or something, then I’ll know.”

The questions that matchmakers ask potential matches are razor–sharp, designed to cut through the surface and reveal as much about the potential match as possible. “‘Tell me about yourself. What are you looking for? Why have your relationships failed? Do you know why? Tell me about your relationship with your mother,’” Daddis says, firing sample questions in rapid succession. “I ask about their upbringing or their relationship with their siblings.”

Beyond intimately understanding the matches, the questions are also intended to gauge a sense of the match’s communication style. Once the matchmaker feels like they have found a good match for their client, they write up a biography about the match and share photos of the match with their client. It’s not just matchmakers who are asking questions throughout the process; Daddis’ clients often bombard her with questions about why she believes the match is a good pairing.

Now, on to the fun part—if both parties demonstrate interest, they proceed to the next point: a date. At that point, the matchmaker momentarily steps out of the frame and follows up with both the client and the match to hear how things went.

“Some of the times it’s my client who wasn’t really into the match, and then the match was really into my client, so then I handle that.” Daddis says. “There’s really no typical [outcome]. Once I introduce them, I kind of saddle up and go for the ride, because I can’t control how anything happens.”

Though the ride can be quite turbulent, many clients try to exert control where they can, such as by drawing hard boundaries around what they want. Common filters include ethnicity, politics, and religion. Among women, though, one preference surfaces more than any other: height. “That’s the one that makes me chuckle, and it’s funny, because the women that are sticklers for heights usually end up having really great dates with men that they would not swipe on otherwise, if they didn’t have me to push [them] and be like, ‘What’s one inch?’” Daddis laughs.

These kinds of interactions, Daddis says, are exactly what Materialists got right. The film’s depiction of matchmaking was oversimplified and slightly inaccurate, but the portrayal of clients felt uncannily real. “Those things were verbatim things that people say to me: what they want, what they deserve, what they are hoping for, their hopes and dreams,” Daddis says. “All of those things, they were spot on.”

In the end, matchmaking isn’t about manufacturing the perfect partner. Rather, it’s about helping people expand their idea of what love can look like. Sometimes, that means nudging someone past a rigid checklist. Other times, it means opening a door they didn’t even know was there. Daddis recalls a female client who had only dated women and came to her wanting to explore dating men for the first time. “She’s marrying a man now,” Daddis says. “People come to us for all different things.”

Daddis’ advice for Penn students who are looking to couple up is as predicted—to sign up for Three Day Rule.

“At least just put your name in the hat,” Daddis says. “It’s just another place to make yourself available.”