Walking through Delhi’s bustling Sarojini Nagar Market, I found myself swept into a stream of unremitting sound, heat, and motion. The morning air was heavy with a torrid warmth, tinged with the sweet smell of frying chaats. Yellow and green tuk–tuks darted alongside the road while vendors called out their wares: vibrant bangles, lehenga cholis, glittering rows of pendants.

Searching for my friends amidst the swarming crowd, I find them sitting in a small spice shop, tucked away from the roadside chaos. The vendor greets me with a smile and offers a steaming cup of chai, fragrant with cardamom and ginger.

I hesitate. In the United States, you’re taught to never accept drinks from strangers. Yet here it seems to be a natural gesture among strangers. My friends sip the complimentary chai while the vendor asks us where we’re from and insists we accept more free samples from his store.

That moment—standing in a crowded market, sharing tea with friends I had just met and a vendor I would never see again—marks my first exposure to India’s collectivist culture. While unassuming, the fleeting interaction reflects the country’s shining ethos: connection over transaction, community before the individual.

The sense of cultural interrelation pulses beneath the city, woven throughout its rich historical preservation and daily practices. Back in Philadelphia, I had grown accustomed to quick solo lunches at Pret a Manger or a brief trip to Houston Market before my next lecture. In Delhi, meals are not driven by routine, but rather, a longing to strengthen bonds with friends, colleagues, or family. A few weeks into my internship, I find myself on the receiving end of that same warmth after local representatives from Penn Institute for the Advanced Study of India invite me to lunch.

We go to a North Indian restaurant that serves meals in the traditional thali style: a large circular plate with small bowls of various dishes—lentils, vegetables, rice, chutneys, curries, sole, and paneer. Instead of ordering separately, the bowls are simply passed around the table. “Taste this, it’s a South Indian staple,” one representative says, spooning a masala–spiced dosa onto my plate. Another offers me a bit of her chicken curry to sample.

Here, the food belongs to everyone. A similar sentiment pervades the table discourse. While most “professional” lunches in the United States tend to be constrained by distant formalities, ours allows for more open conversation that transcends monotonous small talk and surface–level niceties. We talk about everything from Delhi’s chaotic traffic patterns to the politics shaping India’s public health system. They share stories of traveling to different corners of the country and ask me about my family back home. Through something as simple as a shared meal, I temporarily shed my role as a peripheral outsider and experience the beauty entrenched within Indian collectivism. It reveals itself not as an abstract cultural concept but a living practice, one built on genuine curiosity, hospitality, and a willingness to accept a foreigner into its embrace.

Even in the workplace, my colleagues arrive with tiffins stacked high with home–cooked food: dal, paneer, sabzi, and chapatis. Although most days I find myself eating a simple Subway sandwich, others will always come up to my cubicle and offer pieces of their own meals without hesitation. Food’s communality acts as a bridge, a way to overcome the cultural gap that exists between us. Their gestures aren’t mired in grandeur but are small acts of belonging, mixed into the tedious rhythm of the workday.

Community in India isn’t limited to workplaces or restaurants; it’s dually embedded in the country’s spirituality and religious rites. While driving to a nearby city in Haryana, India, I notice throngs of men running down the highway, wearing bright pink clothing and carrying large bottles of water. My driver explains that it was part of Shravani Mela, a month–long festival where devotees travel, often on foot, to collect holy water from the Ganges River and bring it back to temples dedicated to Lord Shiva.

Most of the men run toward the temple for miles, holding onto their water–filled containers as offerings. It isn’t a competition, and no one seems alone—families, friends, and strangers rally around the men, cheering them on as they persevere through physical exhaustion and scalding heat.

As I observe the men with curious admiration, it strikes me how physical devotion emerges as an alternate form of community, a shared spiritual purpose that transforms mundane highways into celebrated pilgrimages. It isn’t just about the individual’s offering, but also the festival’s intent to unite the city through shared experiences of faith and endurance. In the United States, faith often feels private, a ritual to be practiced behind closed doors and intimate circles. In Haryana, it spills onto the roads, acting as a breathing embodiment of the nation’s collective piety.

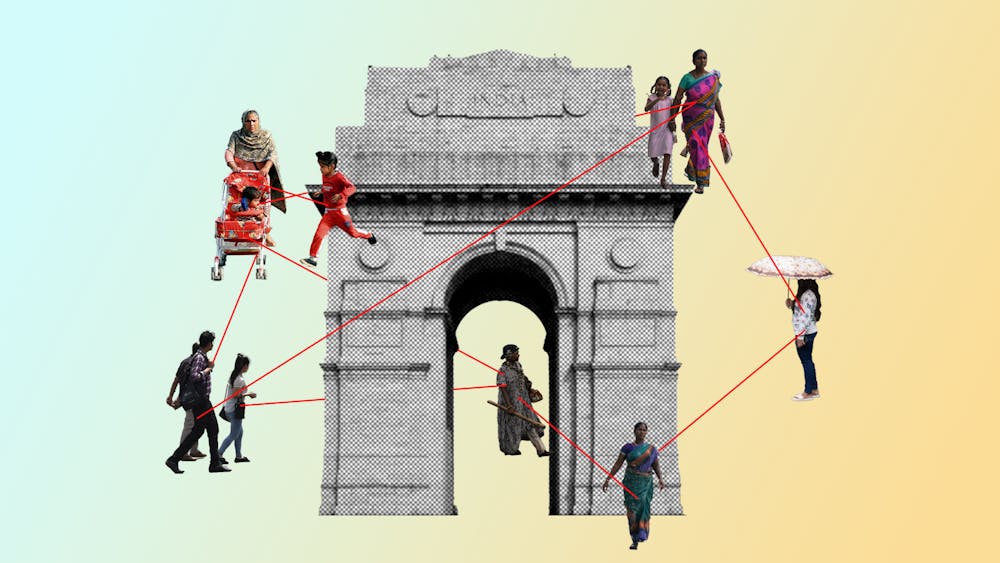

Beyond local festivals, public life feels more relational than the lifestyle that I’m acclimated to at home. In the United States, daily life becomes parallel play: strangers seamlessly move alongside one another but rarely intersect. In Delhi, I cannot walk through the market or visit a monument without one minor connection, even if it’s just a smile, a friendly conversation, or an offer of help. It felt overwhelming at first, but I’ve grown to find comfort in the city’s interconnected nature.

Before living in Delhi, I associated freedom with unbridled individualism, the ability to set boundaries that kept my life separate from those around me. However, my time here has shown me that freedom and collectivism are not always mutually exclusive. There’s a certain sense of liberation in the city’s communal meals, shared celebrations, and market culture that is evidently absent from the United States.

When I return to the United States, I know I’ll still cherish my solitude. I’ll still wear headphones on long walks and dodge Locust Walk’s crowded walkways. But now I know that independence doesn’t have to mean isolation, and community doesn’t always necessitate conformity. Back home, I want to blur the arbitrary boundaries between collectivism and individualism. I want to emulate Delhi’s proclivity to uninhibitedly reach out, share, and celebrate across cultural divides. The lesson I’ll carry home with me is simple yet powerful: joy can be found in joining a crowded lunch table, sharing a cup of chai with friends, swapping stories with affable vendors at the market. These ordinary moments stitch people together in quiet, enduring ways, transforming individual lives into a beautifully composite tapestry.