“It’s our National Day. We are happy and gay!” proclaims one line high above the frames of the Arthur Ross Gallery. “When I grew up, we were expected to be happy and gay, by the government, by the Party,” cries out another. Read once, the words sound chirpy. Read twice, they leave a bad taste in the mouth, like a smile that was rehearsed too many times. That is the structure of Hung Liu: Happy and Gay—a promise, then a question.

Hung Liu (1948–2021) knew those promises all too well. Born in Changchun, China as the Chinese Civil War was still ongoing, Liu lived through famine, war, and the Cultural Revolution. Even when she later emigrated to the United States in 1984, she carried with her archives of classroom primers, family snapshots, and small storybooks known as xiaorenshu and lianhuanhua. Like Dick and Jane books in postwar America, they taught children to be industrious, patriotic, obedient, and, most importantly, happy and gay. The Arthur Ross exhibition, curated by Dorothy Moss with graduate students from Georgetown University, centers on Liu’s late works, which scale up the pages of those storybooks. Here, the works of Maoist propaganda are projected onto canvases too large to ignore, only to have their surfaces warped by oil drips, embedded objects, and abstractions.

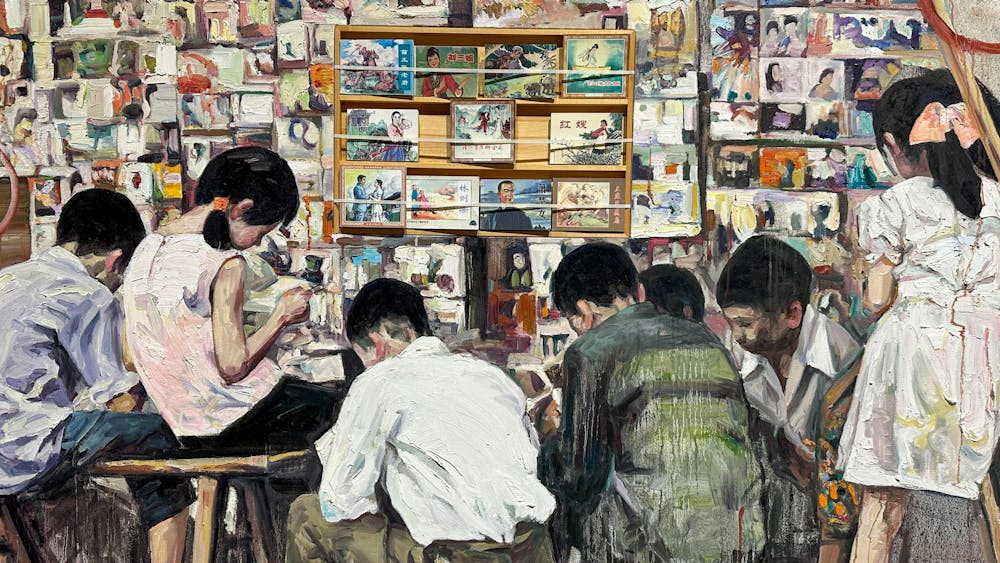

At first sight, Street Library (2013) looks like a memory painted as it truly was. Children crowd around a sidewalk stall with their backs bent over penny–a–day booklets, their concentration almost too heavy for such flimsy paper. This kind of comic–style picture book flourished after 1949, full of myths, heroic tales, and revolutionary stories. Into this painting, Liu inserts a real shelf stacked with vintage xiaorenshu, so that the books are here with us as more than representations. At the same time, she presents us with the very books that both offered her escape and taught her compliance. The small pleasure of getting lost in a story was somehow inseparable from the values the state wanted to instill in children. Liu lets this contradiction hold without necessarily resolving it; as a result, the work becomes less about nostalgia than about the duality of images.

This tension comes through again in Red Flag Flowing (2012), where a child strides forward beside the national flag, which has been reduced to abstraction. It is only after seeing the flag in the boy’s hands that these thick brushstrokes of red bearing a yellow circle reveal themselves as the Chinese flag. The boy's rose–colored face seems to be unaware of the mud drips running down his path. The wall label calls the contrast “harrowing,” and it kind of is. He carries the state’s optimism, while his surroundings refuse to hold that optimism intact: From drips to uneven textures, they turn the steady march into a step that moves forward, yet also sinks into the earth. The label also points to “the discrepancies between the ideals of communism and the lived realities of those subjected to its regime.” Like Street Library, however, Red Flag Flowing does not try to narrow that gap. Instead, it lets the ideal and the lived stand together.

The reception was hosted by the esteemed History of Art professor Gwendolyn DuBois Shaw and the Arthur Ross Gallery Undergraduate Board on Sept. 5. There, Moss and Liu’s husband Jeff Kelley discussed the works in the exhibition with obvious affection. Kelley, an art critic in his own right, unfolded the symbolism of Liu’s work—be it the drips of loose paint representing the “dissolute” nature of memory, or the “798” in the piece Happy and Gay: Father (2012) working as a double entendre that references both the mass scale of the factory system and the designation for Beijing’s contemporary art zone. An audience of Penn students and faculty, the Georgetown class that researched the works, and impeccably dressed Philly elders leaned in for details like these. Together, Moss and Kelley revealed Liu’s semiotically layered works with unusual depth, and it was a real pleasure for anyone who attended the reception.

More than anything, this exhibition made me think of Vietnam. In Hanoi, where I come from, Marx and Lenin still look down from propaganda posters along the streets I walk. 20th–century Vietnamese propaganda valorized patriotic struggle and anti–American resistance through short, terse slogans even the illiterate could read. Today, it urges environmental protection, respect for elders, unity between workers, and even a belief in the Party’s permanence, not unlike what Liu paints against. Its presence has become a part of the streets of Vietnam and the minds of Vietnamese people. Sometimes I stop noticing, until I suddenly see them again, when the poster’s flat, perfect color brightens a rainy day. Propaganda fades, then flares back, and in that persistence, I see how Liu’s works press memory into a question she never quite let go of.

Walking out, I kept returning to one line on the gallery wall: “I never thought of happiness as something reachable. Happiness is a process … not something you can hold onto.” Liu undoubtedly depicts this process in paint. To me, he work almost reads as a confession—one born of a childhood of state pedagogy, years of training in Socialist Realism, political turbulence under Mao, and the crushing weight of images that promised what feels like too much. But an understanding of that world only came once she looked back at her life from across an ocean.

Hung Liu: Happy and Gay runs at the Arthur Ross Gallery through Oct. 26, 2025.