I met Lou Reed through a boy with pale blue eyes—which is to say I fell in love for the first time—and even if he only played The Velvet Underground for the bit, I kept listening long after he was gone. The Velvet Underground didn’t sound like The Beatles or The Stones or anything glossy. They sounded like rot, like sex, like you could bleed out in the East Village and the record would keep spinning. Reed, the group’s principal songwriter, died on Oct. 27, 2013, and he would’ve hated this article.

Reed was raised in suburban Long Island by Jewish parents who didn’t quite know what to do with a kid who wanted to write poetry and kiss boys. At Syracuse, he studied poetry under Delmore Schwartz, a fallen literary star whose ghost haunted Reed’s lyrics—the two men shared an obsession with language, with rot and boys who waste their brilliance in cheap apartments. Reed wanted to be a rockstar, and a sex symbol, and a monster. He wanted to be Bob Dylan but dirtier, Warhol’s favorite freak, and Whitman’s lost son—he wanted to be a poet disguised as a degenerate, or maybe the opposite. His voice was flat but magnetic—it was like he didn’t care if you listened, which only made you want to more.

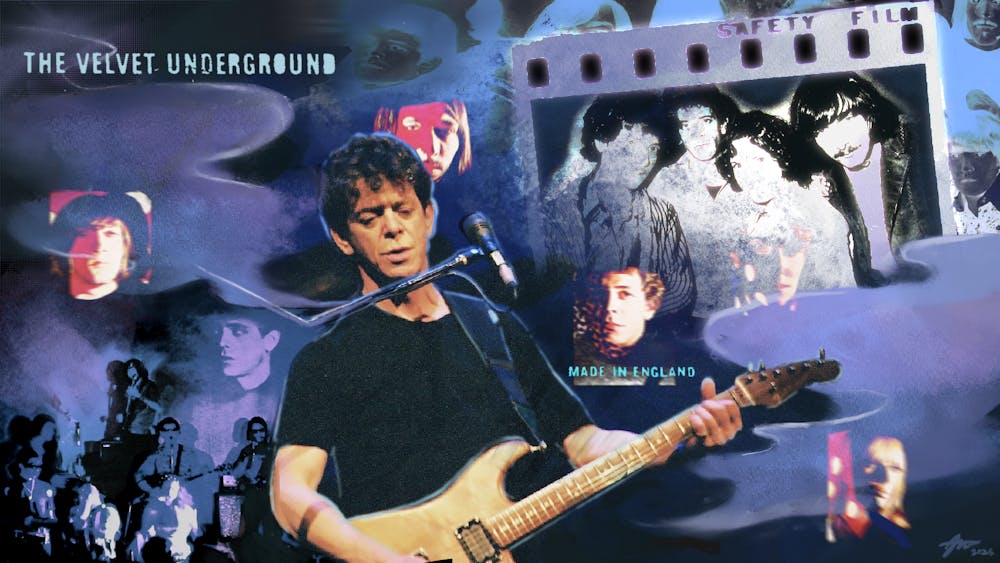

The Velvet Underground was never really Reed’s band, but it was his laboratory. With John Cale, Maureen Tucker, and Sterling Morrison, he tested how far a song could decay before it died. Those early records—feedback–drenched and minimalistic—were experiments disguised as rock albums. Cale brought the art school dissonance, Tucker the trance–like percussion, and Warhol the permission to be uncommercial. When Reed went solo, he kept the raw storytelling, but swapped the chaos for control. Transformer, his second studio album, washed off the grime, turning the East Village into glam theatre. Berlin, his third, stripped it bare again—domestic misery as opera.

“Pale Blue Eyes” (1969, The Velvet Underground)

This is Reed at his quietest, which is probably why it hurts the most. There’s no heroin, no violence, no snarling—just a slow, jangly guitar and a man trying not to fall apart. “Pale Blue Eyes” was recorded for VU’s third album, after Cale left the band, and you can hear his absence—the song is gentler, less abrasive than their previous stuff, almost bare. Reed originally wrote it about Shelley Albin, his first serious girlfriend, who had just married. It’s not really a love song, which might make it the best love song of all time. Reed mourns someone who isn’t dead and wants something he’ll never have. It’s about not being chosen. The line “the fact that you’re married only proves that you’re my best friend, and it’s truly, truly a sin” hits home, depicting grief and delusion in the most beautiful way possible.

The boy I loved had pale blue eyes, and this was his favorite song. I used to think that meant something, that we shared a secret Reed would’ve understood. But that’s the trick of the song: it makes sin feel sacred, like being wrong is just another way of being human.

“Sweet Jane” (1970, Loaded)

If “Pale Blue Eyes” is about wanting something you can’t have, “Sweet Jane” is about wanting everything at once. Sonically, it’s probably the prettiest Velvet Underground song—jangly, melodic, and actually joyful in a way that feels suspicious coming from Reed. It’s him pretending, for a few minutes, that rock and roll can still sound like salvation. The sweetness is a front: “Standing on the corner / suitcase in her hand.” Jane’s not a muse; she’s just another archetype Reed can’t save. The song’s tension is what makes it brilliant, its euphoric guitar riff colliding with lyrics that sound like a breakup you haven’t accepted yet. His delivery is so casual it borders on cruel.

“Stephanie Says” (Recorded in 1968, released later on VU, 1985)

“Stephanie Says” is Reed’s prettiest obituary. The strings shimmer, the glockenspiel sounds like icicles cracking, and Nico’s ghost lingers even though she doesn’t sing a note. Stephanie could be anyone—an alias, or a composite of Warhol’s Superstars who haunted The Factory in fur coats and trauma. She’s cold, distant, perpetually misunderstood, which basically makes her the blueprint for every sad girl archetype after 1968. Lyrically, it’s detached in that classic Reed way—observing her from across the room, never intervening. Production–wise, it’s uncharacteristically ornate for the Velvets: you can hear Cale’s classical fingerprints in the way the arrangement keeps threatening to float away.

“Stephanie Says” sits in the Reed canon as his most deceptive work—it sounds sweet, but it’s really about alienation. It’s the prototype for the heroin–chic aesthetic that fashion and indie culture would repackage for decades: the beautiful woman who can’t feel anything, and the man who mistakes that detachment for depth. Reed never wrote another song quite like it because he couldn’t; by the time he went solo, he’d stopped pretending alienation was beautiful. It’s also an early sketch for “Caroline Says II” from Berlin, a song about a woman who can’t keep living in other people’s fantasies. That’s Reed’s favorite theme, really: beautiful people destroying themselves for an audience that isn’t looking.

“I’ll Be Your Mirror” & “Femme Fatale” (1967, The Velvet Underground & Nico)

Reed said Nico couldn’t sing, and then he wrote her the most delicate song of his career. “I’ll Be Your Mirror” is so gentle it’s unnerving. It’s one of the only VU songs that feels like a lullaby, but the intimacy is still Reed–coded: emotionally stunted, hesitant, and trying to sound like comfort without fully knowing what that means.

He reportedly wrote it for Nico after she said something like, “I do not understand what you mean,” which makes sense—this isn’t really a love song. It’s a translation. He’s offering himself up as a mirror because she won’t let him in any other way. “I find it hard to believe you don’t know / the beauty you are” sounds so desperate, like an artist trying to fix a girl just so she can keep being his muse. He offers his version and tells her to look. And yet it’s also the softest thing Reed ever wrote. That’s what makes it so interesting. He wasn’t known for tenderness, but he gave it to her—through gritted teeth, maybe, but he gave it nonetheless.

Then there’s “Femme Fatale,” which is basically a warning label masquerading as a song. “She’s gonna break your heart in two, it’s true.” The lyrics are catty, even cruel. It’s Reed weaponizing the male gaze and Nico reciting it as if she’s heard it before. The entire thing feels like a dare—like Reed is asking her to sing about what he thought people saw when they looked at her. This isn’t her perspective at all, but his; the outside looking in, loaded with projection and maybe even punishment.

Their relationship is one of those cultural rabbit holes where the more you learn, the less you know. Some say he hated her. Some say he was obsessed with her. Some say “I’ll Be Your Mirror” was a love letter. Others say he wanted to control the sound of the band and she got in the way. It was probably all of these things at once.

“Romeo Had Juliette” (1989, New York)

This is the best poem Reed ever wrote, full stop. “Romeo Had Juliette” sounds like what would happen if Holden Caulfield got caught in a Martin Scorsese tracking shot and suddenly had to admit he believed in love. It’s a song about a doomed couple in the Bronx, sure, but it’s really about New York as a place where love and violence bleed into each other. You cannot separate this song from the smell of trash in the summer and the feeling of being 17 and immortal and stupid. It’s a city symphony where no one wins.

The first line—“Caught between the twisted stars / the plotted lines / the faulty map that brought Columbus to New York”—is so dense it feels like a dare. The song doesn’t follow a typical verse–chorus structure because it’s a prophetic epic. Every line is overstuffed, hyper–specific, and unsentimental—and that’s exactly what makes it so emotional. It’s about two people falling in love in a city that wants them dead and that's precisely what makes it so romantic. This song drove me insane for three years. It was also a favorite of the boy who introduced me to the Velvet Underground.

“Walk on the Wild Side” (1972, Transformer)

“Walk on the Wild Side” is what happens when Reed decides to be empathetic without explaining himself. Every verse is a mini–portrait: Holly, Candy, Joe, Sugar Plum, Jackie. Trans girls, sex workers, drag queens, addicts, artists, factory girls, and downtown freaks are all treated with the same flat, beautiful reverence.

People love to talk about how controversial the song is, but it’s his casualness that really makes it revolutionary. He gave people immortality at a time when no one else cared if they lived or died. Sure, the lyrics are voyeuristic (it’s still Reed) but they’re never mocking. He’s reporting, not moralizing. And the production (thanks to David Bowie and Mick Ronson) makes it dreamy and smooth, almost hypnotic. You don’t even realize you’re listening to a series of character studies about marginalized people because the song doesn’t frame them as marginalized. They’re just living.

The aesthetic they left behind still lingers, threaded through fashion editorials, moodboards, and runways that pretend not to know where they stole their ideas from. Marc Jacobs Fall/Winter ’93, Hedi Slimane’s Dior Homme shows, Saint Laurent’s heroin chic years—all of them owe something to the sad glamour the Velvets made iconic. Hollowed–out eyes, disheveled furs, factory girls in perfect disarray. Reed might’ve hated being part of a “look,” but it’s a legacy he helped shape: beauty that knows it’s rotting and looks you dead in the eye anyway.

That refusal to moralize is why Reed’s music still hits today, especially if you’re someone who lives in the emotional gray. His songs ask if you’ve felt anything honestly. They give space to every version of you—the voyeur, the liar, the one who didn’t leave when it got ugly. And somehow, that makes it feel safe—like even your worst parts could still make a great verse.

“Pale Blue Eyes” still ruins me every time. “Romeo Had Juliette” is still the most romantic thing I’ve ever heard. I think Reed understood something that most people don’t: being seen doesn’t always mean being loved, and being loved doesn’t always mean being chosen—but the music keeps playing anyway.