It’s a daunting feat to successfully mix an action–comedy blockbuster with a prestige political thriller, but Paul Thomas Anderson does just that with One Battle After Another. The nearly three–hour film packs in everything from exhilarating shootouts to family drama, from “a few small beers” to reflections on political violence—and with such broad strokes of its brush, it’s no wonder that it’s been dubbed the “most controversial” film of the year.

NPR praised One Battle After Another as a revolutionary film that could dominate awards season. On the other hand, the National Review lambasted Anderson’s new release as a “reckless ode to radical terrorism.” The outrage and acclaim both seem to stem from the same misunderstanding: that One Battle After Another is Anderson’s revolutionary manifesto. But these polarized reactions say less about the film than they do about our own urge to categorize art as either “safe” or “radical.” At its core, One Battle After Another isn’t interested in glorifying the perfect revolutionary. Instead, it dismantles the myth that such a figure even exists and showcases how the pursuit of perfection holds back real progress in both the fictional and the real worlds. Anderson’s film finds its power in its depiction of flawed but deeply human moments of care and resistance.

Set in a barely alternate version of America, the film is both darkly satirical and eerily familiar, from militarized immigration raids terrorizing towns to government officials colluding with extremist cults behind closed doors. Still, Anderson resists the ease of an explicit dystopian framing. One Battle After Another is set in a world that directly mirrors our own—not in the past or future, but the present. Its power to connect with audiences lies in its responsiveness to our moment—the realization that what Anderson imagines isn’t ancient history or speculative fiction, but a reflection of our reality right now.

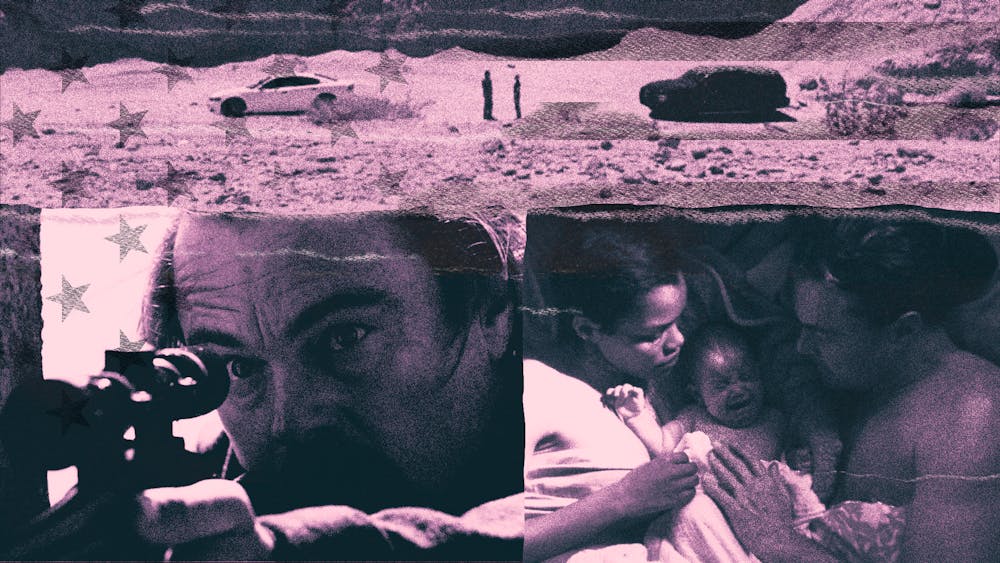

The film opens with the fictional radical group the French 75 liberating migrants in a U.S. border camp. Demolitions expert Ghetto Pat (Leonardo DiCaprio) creates a distraction while the group’s de facto leader Perfidia Beverley Hills (Teyana Taylor) shares a tense, sexually charged exchange with camp commander Steven Lockjaw (Sean Penn). In a thrilling but tempered montage of political violence, we watch the French 75 intimidate anti–abortion politicians and blow up empty buildings. Perfidia and Pat begin a freaky romance—making out in the car after the raid, flirting over bomb–making lessons, initiating sex while next to a transmission tower primed to explode. While Perfidia plants a bomb, Lockjaw catches her but promises to let her go if she’ll meet him that evening. She does, keeping the affair a secret from Pat, and becomes pregnant without knowing which man is the father.

Things fall apart after the birth of baby Charlene as Pat and Perfidia come to a clash over ideology, their conflicts further compounded by Perfidia’s postpartum depression. She returns to the battlefield without him, and after a bank robbery goes wrong, Lockjaw convinces Perfidia to rat out her comrades. He places her in witness protection in a tiny suburb, but she escapes to Mexico after refusing to become his attic wife. The others aren’t so lucky. The French 75 are massacred, forcing Pat and Charlene to adopt new identities—Bob and Willa Ferguson—as they go on the run. Sixteen years later, the father–daugher duo live in a sanctuary city called Baktan Cross.

From there, the urgency of revolution is replaced by the grief of aging. Bob spends his days getting high and watching The Battle of Algiers, consumed by paranoia over his daughter’s safety—fears that are realized when Lockjaw leads a military siege on Baktan Cross to hunt down Willa (breakout star Chase Infiniti).

Lockjaw’s reasons for finding the biracial Willa are, frankly, gross. He believes she may be his daughter, a revelation that would threaten his goal of being initiated into an uber–powerful, purity–minded white supremacist organization called the Christmas Adventures Club (“Hail Saint Nick!”). This subplot crystallizes what the film is really about—not moral purity, but the messiness of ideological perfection. Anderson uses the Christmas Adventures’ obsession with “purity” as a critique of all kinds of perfectionism, from the political to the personal. It’s present in the way Perfidia’s resentment toward Bob for prioritizing their daughter over the revolution fractures their relationship, and in how the mysterious voice over the phone demands cryptic codes to prove Bob has “read the literature” instead of telling him where to find his child. The characters in One Battle After Another are ensnared by the same delusion: that righteousness must be absolute to be meaningful.

Despite its political timeliness, One Battle After Another very much remains a mainstream Hollywood production. Its centrist marketing and collaboration with Fortnite—an absurdist attempt to appeal to younger audiences—are just as intertwined with the film as the Gil Scott–Heron needle drops or the horrific implications of an official medal of honor being named after slave trader, Confederate general, and KKK Grand Wizard Nathan Bedford Forrest. The film’s contradictions hold up a mirror to America’s own—a nation that condemns extremism while glorifying violence and preaches unity while profiting off of division. Anderson calls for honesty over ideological perfection, embracing the shortcomings of his characters with empathy.

Nowhere is that clearer than in the film’s strongest sequence, which follows Sensei Sergio St. Carlos (Benecio del Toro). Initially introduced as Willa’s perpetually chill karate instructor, we quickly learn that the Sensei is running a massive underground network supporting undocumented migrants—in his words, a real “Latino Harriet Tubman situation.” In a kinetic oner, he orchestrates the safe evacuation of dozens of refugees, and even coordinates a group of parkouring skateboarders to lead Bob to safety. In the film’s most grounded scene, Anderson shows how the small acts of trust and bravery between ordinary people can change lives. Through these details, the film captures that real solidarity is sometimes nothing more than a group of exhausted people helping each other along.

Unlike the pessimistic view of activism shown in films like Ari Aster’s Eddington—a COVID–19 neo–Western featuring mask mandates, police brutality, and Antifa terrorists—Anderson’s communities are not numbed by apathy. Even in its bleakest moments, the film insists on compassion. When a former member of the French 75—now operating a guerrilla radio station—is kidnapped, two local kids take notice and send out a warning call on his behalf. When Bob is arrested, a secretary’s leading questions and a nurse’s covert gestures allow him to break out. Even when it feels too little and too late, the effort of caring for others becomes its own kind of victory.

More than anything, One Battle After Another is a meditation on America’s cyclical nature—there are always young people trying to change the world, and there’s always an old guard to be reckoned with. Some people burn out, some people carry on, but no matter what, the fight continues with the next generation. The film isn’t radical or revolutionary, and that’s precisely its strength. It relies on an America that’s tired but passionate, hypocritical but kind. By freeing us from our respective echo chambers, Anderson reminds the audience that perfection was never the goal. The courage of Willa, Sergio, and countless others lies in their refusal to surrender, to keep caring, to always decency over despair. In a culture addicted to outrage, that might be the most radical act of all.