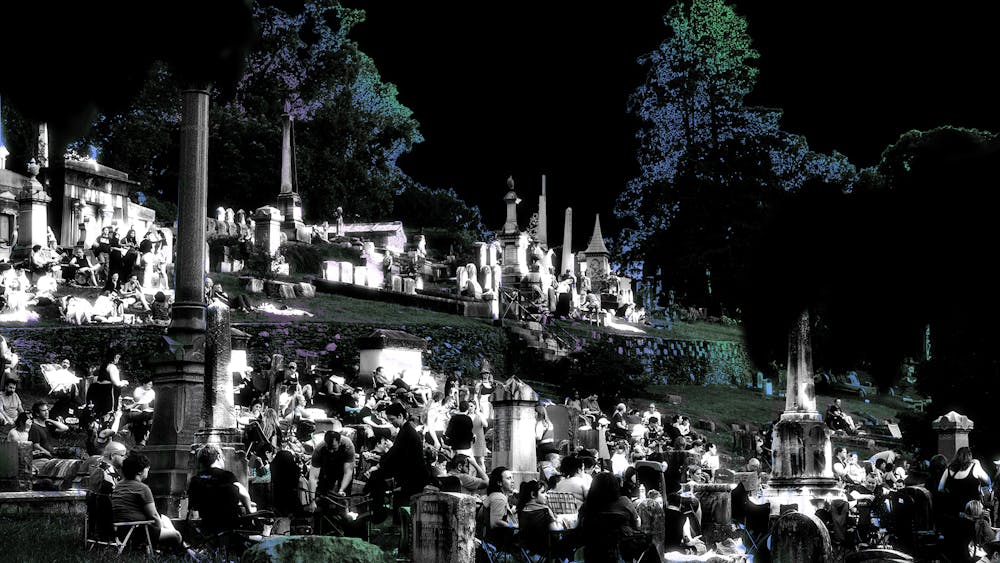

It’s warm and green. Twentysomethings speed by on bikes, and families snack on picnic blankets. Elderly couples walk their dogs together, holding hands. Though some people are quiet, most are silent. This isn’t Fairmount Park or FDR Park, but The Woodlands Cemetery, where the living and the dead have learned the art of cohabitation: The deceased are taking their final rest while the living rejoice around them. Just five miles north of here, Philadelphia residents engage in similar activities at Laurel Hill Cemetery.

Major cemeteries like The Woodlands and Laurel Hill were the first public parks in the United States, providing green space for city folk to dwell in with the dead and creating an escape from the loud and busy streets of the industrial 19th century. Completed in 1836—three decades before Fairmount Park—Laurel Hill was the only space for early Philadelphians to access public recreation. Just four years later, The Woodlands was built.

Mid–century suburbanization changed this: Millions flocked to the green and spacious suburbs, sterile from the grit of the city. Businesses, religious institutions, cemeteries, and funeral homes soon followed. Laurel Hill expanded west to Bala Cynwyd, Pa. from its Philadelphia location, and city cemeteries like Laurel Hill East and The Woodlands experienced mass disinvestment. This was “the impetus for the creation of The Friends of Laurel Hill,” Nancy Goldenberg — who received a Master of City Planning from Penn in 1980 and is CEO of the nonprofit — says.

Goldenberg explains that Laurel Hill’s revival began in the mid–1970s when a local historian proclaimed the space far too historic to be left to waste. He subsequently began leading tours of the grounds to raise awareness of what, in 1998, became the first cemetery in the United States designated as a National Historic Landmark. Laurel Hill has gained a lot of momentum since then, hosting over 100 public programs just last year. From Civil War tours to visits to Adrian Balboa’s fake tomb, these tours bring in tourists from across the nation, and plans for the United States’ 250th anniversary are underway.

This past summer, continuing in an annual tradition, Laurel Hill hosted death–themed movie nights, showing everything from The Rocky Horror Picture Show to David Lynch’s famed Eraserhead and lively food and art markets. A post from @wooder_ice on Instagram back in July about the events produced comments full of controversy, with many excited to attend the screenings and others upset about the cemetery where their loved ones reside being used as a social space.

Goldenberg, however, has rarely felt pushback. “The people that have loved ones buried here have told me they love to see people in the cemetery using it and visiting. … It’s sort of a celebration of life,” she says. “One of the greatest fears I had was welcoming all these people into the cemetery and then, would it be trashed? Would it be graffitied? No, just the opposite. People are very conscientious. Their behavior changes. … And we have experienced people that really respect being in a cemetery.”

One such person, found not in Laurel Hill but reading in The Woodlands, is Egypt, who didn’t provide a last name. After moving to 42nd Street back in June, she now routinely visits the cemetery at least once a week. She “had mixed feelings at first” about using the cemetery as her neighborhood park, but, “trying not to be coarse, they’re dead,” she says. And she’s not alone in this: “It’s a nice community space. I would have never thought of this as like a third space for people to gather in. But I see people all the time. Like, I see people will come over to this bench and they’ll do something like a meetup, or they’ll have a play date with kids. I’ve seen people have weddings here, parties here,” she explains.

Her interest in the cemetery stems not just from a need for a nice green space to relax and do yoga, but also from her critiques of the United States’ relationship to death. “People really turn their face away from death,” she says. “There’s a lot of fear around not just death, but growing older and losing your vitality or your youth. I feel like America is so youth centered. They’re so obsessed with that specific 16–to–21 time period, and they just don’t want to think about life after that.”

This fear keeps people away from cemeteries, she says, and has grown a culture of shame around our dead. We shun them, and do our best to keep the worlds of the living and the dead separate. But “death is the most important thing to remember when you’re alive,” Egypt argues. “There has to be some knowledge and acceptance that it’s gonna end, so that you can fully want to live your life.”

“Realize it’s temporary,” she says. She argues that the American careerist obsession is where our shame around death and our dead comes from. “I think that’s what keeps people in this loop where they just kind of have a ‘work–to–die’ mentality, where they’re putting their head down for 60 years. I feel like that ties into Americans’ general shame around death,” Egypt says. “I feel like you’re gonna have to come to a place where you either don’t think about death at all, or you accept death and you realize you can’t waste your entire life doing something that you fucking hate.” When we get too close to the dead, be it cycling by or reading a book near their grave, we’re struck with the facts of life that we run from. And so by spending time in the cemetery, we’re allowed to sit in our mortality, make peace with it, and celebrate the lives that surround us.

Egypt balances her moral reservations surrounding recreation in cities of the dead by going around and reading the tombstones of those she’s spending time with. “It’s really interesting to just acknowledge how much I don’t know. Everybody who has a headstone here had a life,” she says. “At some point they were important people. You can see it on their headstones with the messages: people who loved them, people who cared about them, people who leave flowers for their graves.”

While growing up in New Orleans, I experienced a similar feeling around death. My friends and I would play in cemeteries, drinking strawberry smoothies at a small cafe in the city’s St. Patrick Cemetery. Death is far from a taboo there, nor is spending time with the city’s quietest residents. To New Orleanians, play and fun is a way to respect the dead, rather than just solace and mourning. As Goldenberg says, it’s a way of celebrating life.

“Our mission is to provide a place of beauty and peace, for eternal rest, for recreation and for civic value, and at the same time, preserve our history and ensure our relevance for future generations,” Goldenberg says. Laurel Hill is used by nearby residents as their local park, with opportunities for biking, picnicking, sitting and reading, or even watching movies. Laurel Hill is also a sanctuary for local wildlife: Sustainability and environmental protection make up some of its other core values.

Laurel Hill’s programming extends beyond its summer movie nights and tours, though. “We are in the death industry, and so we focus on programs that help people with the grieving process,” Goldenberg says. “We have death cafes, and we have a horticulture series where there’s therapeutic horticulture, and even the movies that we do show have themes about death. … We have a book club where we’ll read books that deal with death or deal with nature.” One of its most anticipated events occurred just last month on Sept. 20: Market of the Macabre, an arts and crafts market with over 100 vendors. Many of the products sold are handmade and deal with death, incorporating bones and feathers into their works.

The Woodlands hosts a variety of events as well. From marathon relays to September’s Karaoke in the Cemetery: A Night of Grief Karaoke—hosted by interdisciplinary artist Leigh Davis as a part of her long–term work in art and public grief—the cemetery invites the public to use the space for both recreation and the grieving process. Intentionally opposite in spirit, Davis is hosting her Karaoke in the Cemetery event in some of the East Coast’s most famous cemeteries. She hosts these events with the intention of creating space for public and vocal grief. “I like the mixture of two things that don’t really belong; like karaoke and a cemetery are pretty much opposite. But that’s what makes it, I think, the right fit, because cemeteries are usually really quiet, and I really want this project to be about sound and noise and people expressing [themselves] openly.” She believes that in the modern era, in which we at times struggle to congregate in person, hosting events like this in public spaces is key to building community.

Davis’ work coincides with a larger movement of collective grief and changing sentiments around the public use of cemeteries. “Because there’s been so much mass death,” she says, “I think people are more aware of death in our culture as being a huge weight that people carry. I think there’s a lot of growth that needs to happen around repressing death. So a lot of my work is about how to basically release some of the grief people have.” By creating space for people to sing and dance their grief, she feels that her work connects to the celebrations of life that both our ancestors and modern cultures like that of New Orleans participate in. Karaoke in the Cemetery is therefore a way of returning to “what we used to do” in cemetery spaces, mirroring the active return to public recreation occurring in these same places.

The grief felt in these events isn’t just personal, though. People sing and scream out collective grief for the transgender community and for Palestine and Gaza. “I just feel like everyone [has] such a different take,” Davis says about the grief process. “There was a lot of political grief mixed with individual grief.” The presence of politics in these public grieving events is not shocking, as public spaces like parks, including cemeteries, have always been intertwined with protest and politics.

Laurel Hill, too, actively works to make death less of a taboo. When asked about a moment that particularly represented the mission of the cemetery, Goldenberg remembers a pair of brothers she met several years ago: “There were two brothers who had a big–screen TV hooked up to their car. They were sitting at their father’s grave. They were eating their chicken wings and watching the football game, the Eagles. They were tailgating with their father,” she explains.

The boys’ father was such a Philadelphia Eagles fan that they carved an eagle on his tombstone. Once a year, the two of them come to the cemetery to tailgate the team’s opening game of the season. “And that sums up what we are. We’re a place of comfort to be with your father, who passed away, doing something that you enjoy. You’re recreating having your tailgate and you’re enjoying the game with dad, bringing back those memories. And, you know, this is what we’re all about.”

The Woodlands and The Friends of Laurel Hill create spaces where life can be celebrated and coexist with death. Simultaneously, the cemeteries provide Philadelphians with a green escape from the city, upholding their original secondary function as a public park.

I still avoid going straight home from the cemetery, not wanting to bring any spirits along with me. My mother holds her breath as we drive past graveyards. However, the only ill–spirited experience I’ve had in a cemetery was when I cartwheeled into a red ant pile on an open plot in St. Patrick Cemetery. Maybe karma, maybe just a silly experience for a child playing in a park. That is what cemeteries are, after all.