Picture a girl lying on the floor of her bedroom. Her toy keyboard wheezes out a few wounded chords, her phone is propped up on a half–empty Diet Coke can, and she’s confessing into the mic like God Herself is listening through the preamp—apparently, so is everyone else. A month or so later, her song is released, and the girl’s late–night lamentations become the anthem of a generation just learning how to feel. She is 17, furious, heartbroken, and about to rewrite pop. Her name is Olivia Rodrigo.

“drivers license” played everywhere when it first hit streaming platforms in January 2021, but it always sounded like it belonged in a bedroom. Rodrigo sang about heartbreak with the vulnerability and openness of someone still trying to understand it. The song’s power lay in its sheer, ungoverned sincerity—a revolutionary choice in a era choked by polish and curation.

Rodrigo’s ascent signaled something larger than the success of a single artist. For decades, popular stardom thrived on distance and mystique, curated by management teams and perfected under studio light: Madonna refusing to age, Prince being draped in purple smoke, David Bowie shapeshifting through personas no one could claim to fully understand. Pop stars, after all, were meant to be celestial.

Rodrigo shattered that spell. She arrived on the pop scene in sweatshirts rather than sequins, holding a microphone like a diary. “drivers license” didn’t have a glossy PR campaign, instead dropped after an Instagram Live with Rodrigo wearing a birthday hat in front of a background that read “I got my driver’s license.”

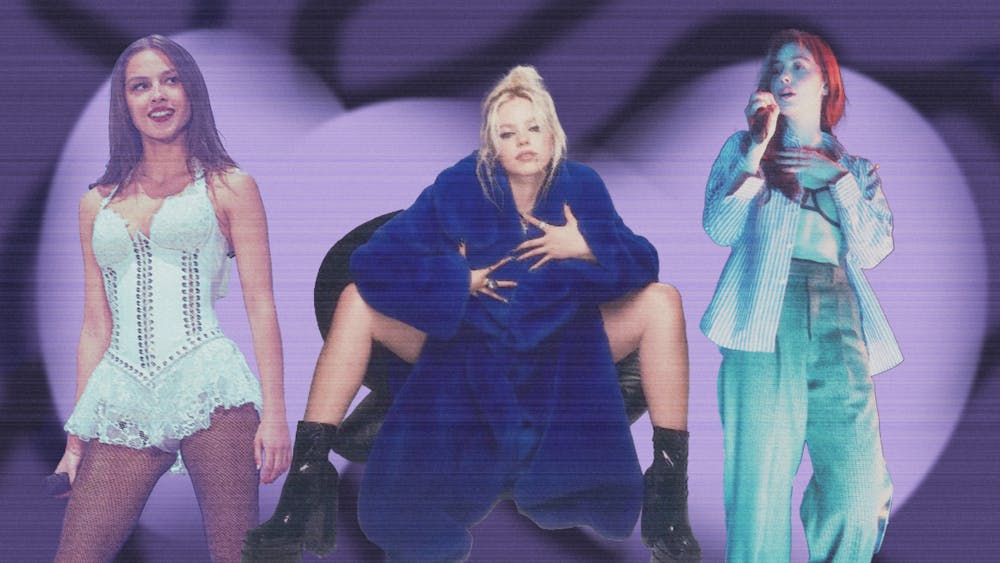

But Rodrigo wasn’t the only one bringing forth this new, authentic energy. Gracie Abrams took the same intimacy and crafted it into whisper–soft songs that sound like they’re meant for that one person who won’t text you back. Reneé Rapp went the opposite way by turning her feelings into catharsis, crying and cursing on stage as if she was daring the crowd to feel it, too. And pop’s newest anti–pop star, Audrey Hobert, sings into the microphone like an elementary schooler trying to convince her parents to let her have a sleepover.

That kind of initial intimacy changed what pop stardom could look like. The old pop icons relied on fantasy; this generation’s power comes from familiarity. Today's pop fans don’t just listen—they echo the artists they love, be it through making montages, belting along in their cars, or rewriting lyrics to frame their own perspectives. The artist, it seems, has become a mirror for the listener.

The success of Rodrigo et. al. says as much about their generation as it does about the music industry. If vulnerability is now pop’s most profitable export, Gen Z is fluent in the language. After all, they’ve been raised on it—the internet as a diary, the Notes app as a therapist, the get–ready–with–mes and “put–a–finger–downs” as a genre of self–exposure.

What once lived in private now launches careers. A shaky iPhone demo can land someone a record deal. A breakup rant can chart on Billboard. The same platforms built for sharing selfies can now become spaces for self–dissection. And it seems that the industry knows this all too well. Labels push artists to “show more of themselves,” to post in pajamas, to share unedited voice memos—because oversharing, as evidenced by Rodrigo’s skyrocket to fame, can be great PR .

It’s easy to be cynical about it, but there’s something ingenious in how Gen Z has redefined the relationship between star and fan. They’ve grown up in a world that rewards visibility, so they’ve learned to weaponize it. But don’t get it wrong—their openness isn’t naïveté. When Rapp spits out “You’re the worst bitch on the Earth / I hate you and your guts / I think you should shut the fuck up and die” to a large crowd, or when Hobert makes a fool of herself in a way that 2000s Britney Spears never would have, it’s easy to pass it all off as self–expression. But that self–expression is exactly what keeps fans coming back. That brand architecture matters just as much.

Pop used to sell fantasy: the perfect love, the untouchable icon. Today, younger artists offer the illusion of closeness, be it manufactured or real—a FaceTime–style intimacy that feels like friendship but fits the needs of capitalism. Call it what you want, but whatever it may be, it works. The songs still make people cry, but the difference is that now everyone’s crying in public. This is what pop looks like when privacy stops being a virtue and starts being a luxury.

Right now, somewhere out there, another teenage girl is sitting on the floor of her bedroom, toy keyboard and all. By morning, she might have a million views, her vulnerabilities folded neatly into the feed. She is proof that in this era, feeling something out loud may be the closest thing we have left to being heard.