[media-credit name="The Barnes Foundation" align="alignright" width="181"][/media-credit]

As I lined up to pick up my tickets for the opening of ‘Yinka Shonibare MBE: Magic Ladders’ at the Barnes Foundation, I found myself surrounded by fur coats, “authentic” prints and thick–rimmed glasses with lenses measuring roughly one and a half to two inches in diameter. A woman in front of me, dressed head–to–toe in purple (including vibrant tights and a hat), was discussing “conceptualizations of rationality” and “the shortcomings of time” with a man wearing a three–piece suit. He nodded slowly whilst warily staring at her hands as they gesticulated rapidly. At this point my thoughts were mostly occupied with the cold weather outside.

After I begrudgingly gave my coat to the mandatory coat check, I entered the main hall space. Next to the bar, which was selling glasses of $8 wine and $10 premium spirits, was a band playing upbeat Latin–meets–Pan–African music, complete with a steel drum. The audience swayed awkwardly to the music, and a few controversial figures were dancing with their eyes closed. Later the music switched from the live band to a DJ, and the awkward bopping persisted.

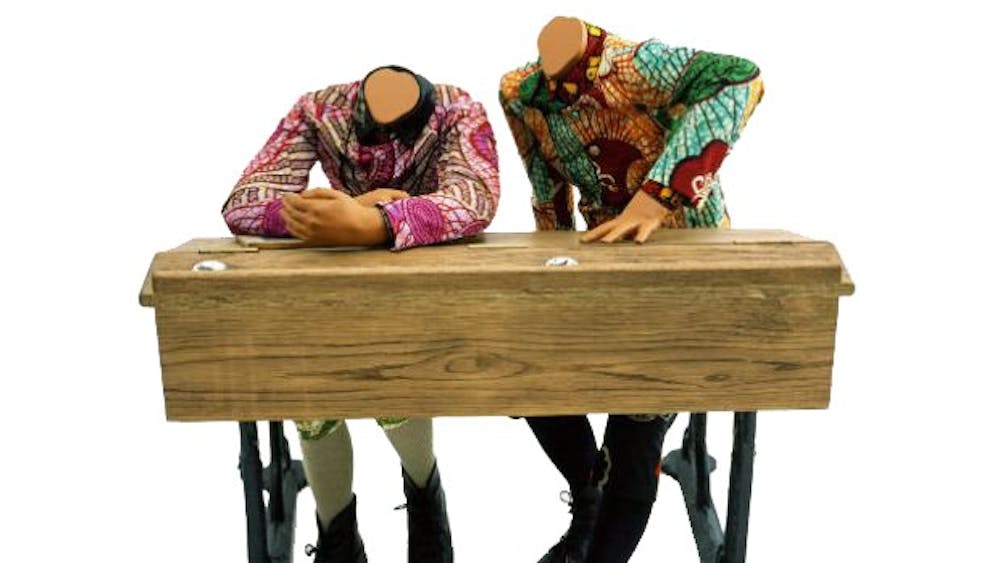

The solo exhibition was held in the large room to the left of the entrance hall. The collection aims to explore the historical, social and political identities of Yinka Shonibare’s Nigerian and British roots. Through the works, Shonibare raises questions on globalization, exoticism, fine art vs. decorative art and enlightenment, among other topics. The three–part centerpiece, ‘Magic Ladders,’ marks the first contemporary commission by the Barnes Foundation since Matisse was hired to create a mural in 1930. The ladders, whose rungs are comprised of Western books on art and philosophy, stand upright, seemingly unsupported. They feature child–sized figures, dressed in batik print clothing, with globes for heads, climbing upwards. The pieces address the pursuit of knowledge, and its relationship with nationality. The subject matter is fitting with Albert C. Barnes’ devotion to education.

Indeed, all 17 of the pieces chosen for the show pay tribute to Barnes’ theories and teachings. Barnes notoriously barred the elite art–goers of his time from entry to his collection, favoring those who he felt truly wanted to learn. Shonibare’s sculptural installations incorporate objects of learning—from telescopes to books on Plato and Immanuel Kant. His combination of African prints, scenes and symbols associated with Western thinking makes his ambition to rewrite history and the legacy of colonialism clear. While primarily focusing on historic culture, Shonibare does include some contemporary imagery—principally pictures of soccer players. The discussion of nobility and elitism is inherent in Shonibare’s name, as when Prince Charles appointed him a Member of the Order of the British Empire (MBE) in 2004. Through his art, Shonibare makes fun of his own airs and graces. Wouldn’t it be nice if people didn’t take themselves so seriously (I say while wearing my own pair of oversized glasses)?

[media-credit name="The Barnes Foundation" align="aligncenter" width="620"][/media-credit]

The Barnes Foundation