In “A Bronx Tale,” young Calogero Anello (Francis Capra) is told by his well–meaning father, Lorenzo (Robert De Niro), “The saddest thing in life is wasted talent.” This concept of continual self–improvement is integral to the Italian–American identity, and “A Bronx Tale” captures this idea better than any other film.

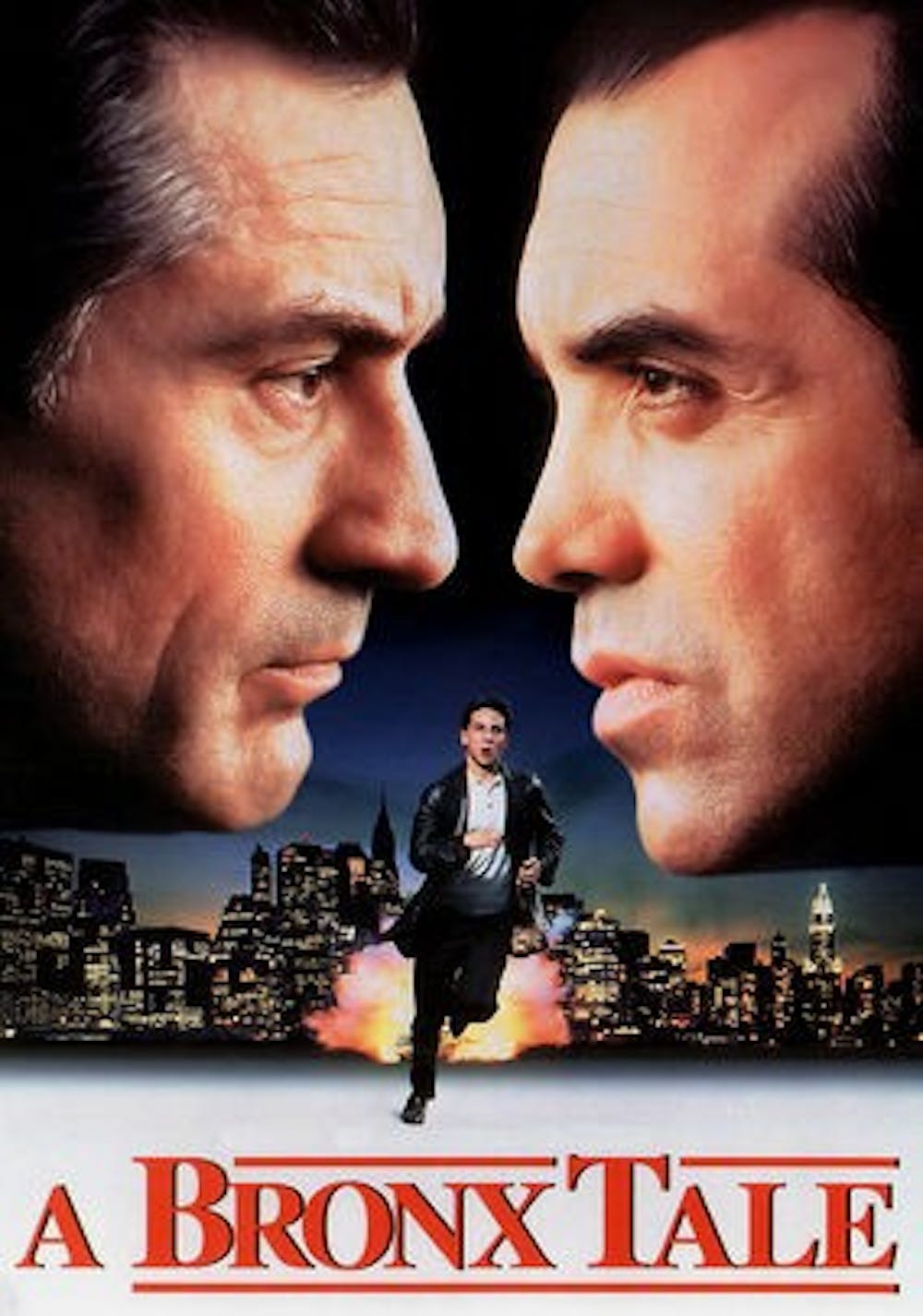

“A Bronx Tale” is essentially an afterthought (if even mentioned at all) in any discussion of gangster films. Far from the realm of baptism–juxtaposed executions and glitzy nightclubs , De Niro’s film set its sights on one street in the Bronx, with its blue collar, Italian–American families. Mob boss Sonny LoSpecchio (Chazz Palminteri) is no Vito Corleone. His operation is local in scope and desire; he collects his payments and keeps mostly to his own stretch of the neighborhood. If law–abiding citizens like Lorenzo wish to keep out of Sonny’s affairs, so be it. Only when Sonny takes Calogero under his wing in gratitude for the boy’s helpful testimony does conflict ensue. Now, the boy faces the classic dilemma between going through life the “easy” way as one of Sonny’s associates, or following in his father’s footsteps as an honest, but poor, bus driver.

The life of the blue–collar, Italian immigrant is crucial to my family’s history. My maternal grandmother immigrated to America at the age of eighteen, joining her father who had been sending paychecks back to Italy for years previously. With an advanced education hardly an option for non–English speakers, my grandmother and her family buckled down in grimy, undesirable jobs. Her father busied away as a railroad worker, and she eventually supported her husband’s butcher shop. My paternal grandfather, upon returning from a five–year stint in World War II, worked night hours as a bank guard. One day, my father came home from his job as a bartender with a sizeable pile of tips. In shock, my grandfather remarked that it was more money than he had ever made in a day.

Better than any movie of its kind, “A Bronx Tale” reflects the Italian–American cultural drive toward progress. Through each generation, the going gets better. My grandfather worked so my father could work for me to work for my children...and so it goes. The unyielding drive toward bettering one’s self and one’s family eschews the “easy way,” including the Mafia. Lest we forget, Mafia members often advance themselves at the expense of other Italians, as my grandmother recalls from growing up in Southern Italy.

Lorenzo Anello rejects his son’s predilection to violence and racketeering, in a way representing the Italian father wanting the best for his American son. Eventually, Sonny is assassinated. Calogero realizes the cost of pursuing the “easy way,” and reconciles with his father. Besides being a cautionary tale against joining the mob, “A Bronx Tale” reaffirms the desire for Italian–Americans to advance themselves in this land. Both Sonny and Lorenzo impress the idea that “The saddest thing in life is wasted talent.” Calogero soon realizes that “wasted talent” is all organized crime is. It is a waste of men and resources, yes, but a waste for all Italians in America. The more they choose to adopt the “easy way,” the harder the journey of acceptance and compatriotism becomes. My identity as an Italian–American comes with knowledge that laziness means “waste” and crime is the sacrifice of talent. My parents taught me that, and so did “A Bronx Tale.”

Check out our other "Living Our Lives in Film" Identity Essays: