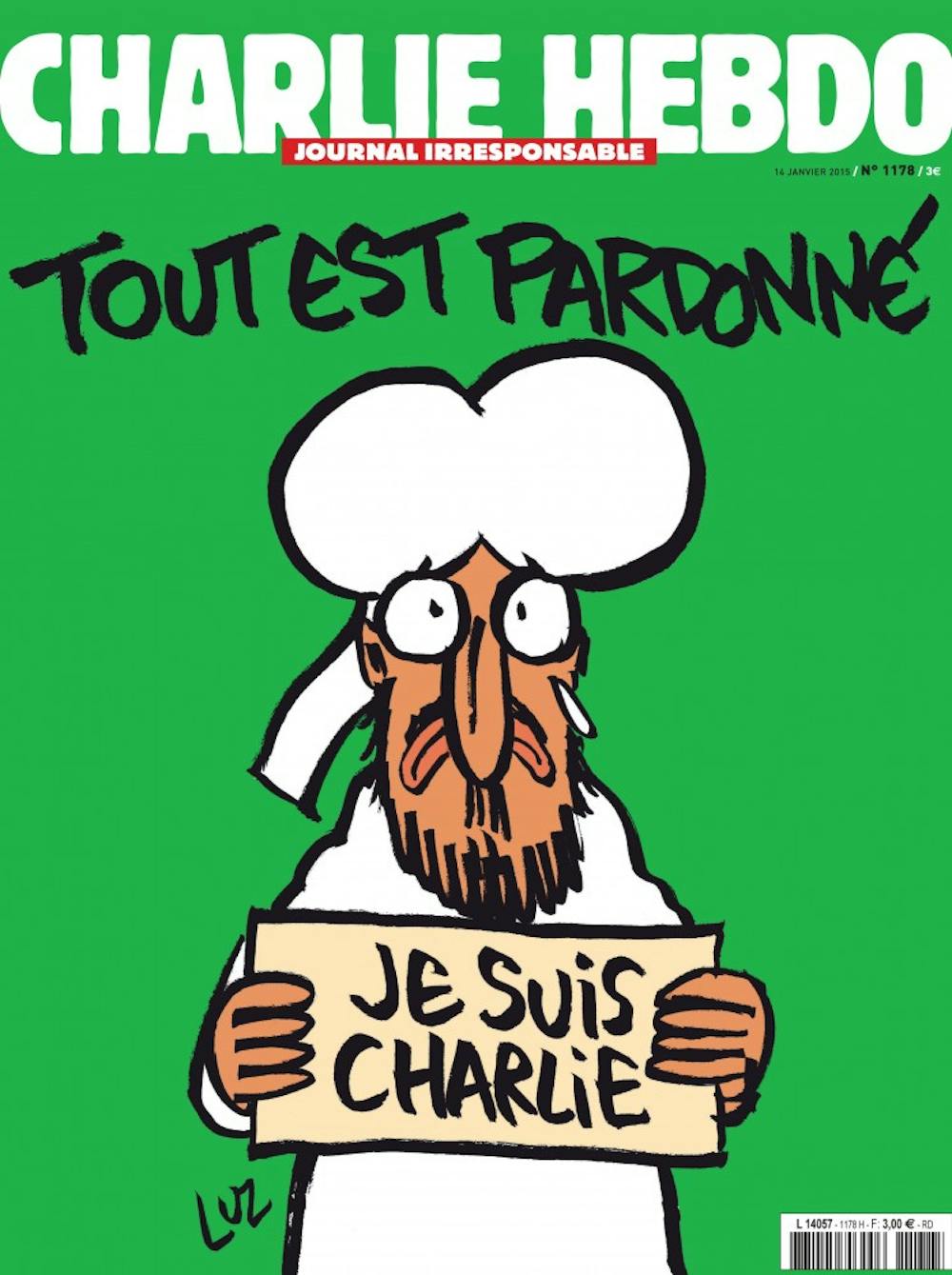

One week into the New Year, Paris underwent three days of fear and despair. We have seen the reaction of millions of French citizens, including from our Penn community, as well as others in New York, Beirut, Sydney, and Berlin. But the most interesting response came from the victims themselves, particularly the weekly satirical newspaper Charlie Hebdo. In less than a week cartoonist Rénald ‘Luz’ Luzier found the inspiration for a cover that would mourn the lost lives of the attacks and show that hope and courage are not lost.

The recent cover portrays—once again—the Prophet Mohammed holding up a sign saying “Je suis Charlie,” shedding a tear, on a bright green background. The cover’s header reads “Tout est pardonné”— “All is forgiven.” The cover certainly does not call for a truce or respite—instead it is a sign of Charlie Hebdo’s cartoonists standing for their artistic freedom. It's a sign that they are not afraid. It's possibly even a sign of forgiveness of the attackers. It is not, however, a declaration of war. Although the depiction of the prophet is considered blasphemous, in this instance it is not meant as derogatory or offensive. The new cover is an invitation to the conversation, and more precisely, to humor. “All is forgiven” expresses the prophet’s invitation to forgive.

While most of their work embodies a satirical and ironic tone, this cover is an honest call for unity and solidarity. The conversation is consistently about the controversial nature of the cover. And yet, one of the least commented aspects takes up the entire page—the color. The bright green overwhelms the page and is filled to the brim with political meaning, yet it still remains overlooked. While the green might be purely an artistic choice, it is interesting that Luz did not pick les couleurs de la République—the bleu and the rouge. Instead, Luz picked a color that became the symbol of a short–lived revolution. In 2009, the Islamic Republic of Iran went through a presidential election: the two main candidates were the standing President Ahmadinejad and Mir-Hossein Mousavi, whose campaign’s color was green. After Mousavi’s loss at the election, Iranian voters came to the streets waving green flags and wearing green bandanas and head scarves, protesting the elections’ inconsistencies. Contrasting the otherwise neutral colors, the green background of the cover symbolizes the strength to cope with adversity.

Cartoonists are both artists and journalists. They create a social commentary with a pencil as their chosen medium. They don’t intend to hurt or attack. The pencil is not meant as a weapon. Artists aim to provoke and spark a conversation, the fruit of their work is designed to make the reader feel, whether that be anger, or amusement, or sadness. If a satirical cartoon hasn’t made its viewer react in any way, feel conflicted or question an idea, then the cartoonist has failed. Voltaire, French philosopher of the enlightenment, once said: “I do not agree with what you have to say, but I’ll defend to the death your right to say it.” The French Republic is built upon one simple concept: “Liberté.” Freedom to express political, artistic and religious opinion. Since 1789, freedom of speech has been a right, not a privilege, that must be preserved and protected. The same way a reader holds the right to embrace or disagree with one’s opinion, an artist or cartoonist holds the right to express his own. In no way are these cartoonists imposing their thoughts on others or expecting everyone to agree, but in no world should a man have the right to take a life in light of disagreement. Charlie Hebdo took risks before the attacks and will continue to do so. The meaning of their work lies with the courage to redefine freedom of speech, not the content of their caricatures.