At least once a day, I see something that prompts me to reach for my phone to text or snap Sarah. Sometimes I put it right back down. Sometimes, I type out a text or take the picture, and then I remember. She’ll never see it. And there’s no one else I want to tell, so my phone slides back into my pocket. Because in every friendship, there are some secrets and jokes that are just between the two of you. They died with her.

It didn’t really hit me until about three weeks after it happened. It hits me every day, in small ways, but that was the moment I knew without a doubt she was gone. I was working on a lab report in Huntsman, and “Live Like We’re Dying” started playing from the random Spotify playlist I was listening to. “If your life passed before you, what would you wish you would’ve done?” I cried silently in the middle of the forum, keeping my head down so no one would see.

I wish I had called her. I wish that when she stopped responding to my texts, I had realized something was wrong. I wish she had called me. I wish I had decided to leave for college a day later. On the car ride back from meeting the movers at my apartment, I thought, “I should call Sam and Sarah to see if they can swing by for ice cream, so we can see each other one last time before we all go back to school.” But there were still things that I needed to pack, and I was tired. They would understand. I could invite them down one weekend so they could finally see Penn and meet everyone, and get to see what the “downtowns” I spoke of were.

But she never made it to the long–promised downtown. That night, she left us forever. She made the choice to end her pain. A week later, while the rest of the school threw on their crop tops and hit the pool party, I dressed in all black and spoke at a memorial service for a 19–year–old, one of my best friends. If you Google “how to write a eulogy,” the Internet has plenty of suggestions. “Discuss their major accomplishments.” “Tell a funny anecdote from their youth.” But what do you say when her accomplishments were just beginning, when her youth was her whole life? A life that was so wonderful, that lit up the lives of everyone who met her, a life that was so at odds with the way it ended. How can you do her justice in a page or two? How could I explain that the person she was in her last moments wasn’t the person that I knew, that she was the sunniest and one of the least judgmental and most compassionate people I have ever known?

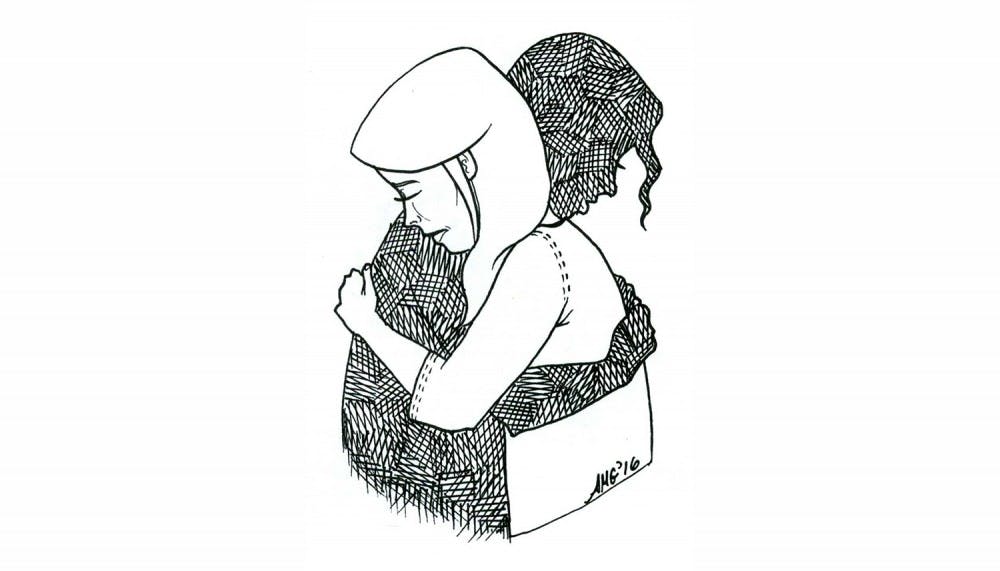

I’m sorry I couldn’t save her. I’m sorry I wasn’t enough. Eventually, I might forgive myself. But it’s not something I’ll ever “get over.” Because when she died, a part of me died with her. There are parts of me that only existed with her, parts that only came together in a certain way when she was around. Those parts of me still exist, but they don’t get to come out in the same way they used to. My dreams for the future had her in them. I used to think of all the fun we would have kicking ass as female engineers, taking our families on vacation together, taking our daughters shopping. Not only do I mourn the loss of the person I knew, but also the person she was becoming that I’ll never get a chance to know. The amazing things she would’ve done as a programmer, a man’s field in which she frequently outshone the boys. The big white and pink wedding that she’ll never have, the husband who would’ve adored her. My heart aches with the realization that it’ll be just me and Sadie at American Girl Place, a table for two blondes that should’ve been for four.

Sarah isn’t here anymore. She’s not coming back. As much as I wish I could, there is nothing I can do to change that. All I can do is remember her fondly, the way she would want to be remembered: beautiful inside and out, in a rare way that most people aren’t. A lover of the color pink, Lilly Pulitzer, monograms and Gossip Girl. An all–around amazing friend and person.

Losing Sarah has changed me. I wish I could say I’ve become a better person, but I don’t think that’s really true. I definitely am more conscious of when people are feeling down and try to reach out to them. But in other ways, I’m a more selfish person. Many times, people’s problems seem trivial, because I can’t help but compare them to what I’m going through. It’s hard for me to be sympathetic in the way I want to be. I try to make up for it whenever I can: hold the elevator, open a door, pick up my roommate’s favorite ice cream, share notes. I apologize endlessly when I realize that I’ve offended or hurt someone. I try to show people that I care. But I suspect that right now, I’m asking for more of others than I’m able to give them.

I’ve accepted that she’s gone, but I still have a way to go before I can get back to whatever “normal” is like for me now. The harder part to swallow is the unknown—accepting that there are questions I will never know the answers to. I’ve always believed that things happen for a reason, but I’ll never understand why it had to end this way. I can’t see what was accomplished by her passing that couldn’t have been done another way. I can’t see the good that’s come from such a wonderful person being taken from the world.

Why, God? Why, Sarah? Why?

But all I hear is silence.