Among Netflix’s newest additions this April is A Land Imagined: the Singaporean, neo–noir winner of the 71st Locarno Film Festival’s Golden Leopard. Sounds niche—but neo–noir might be more familiar than you think.

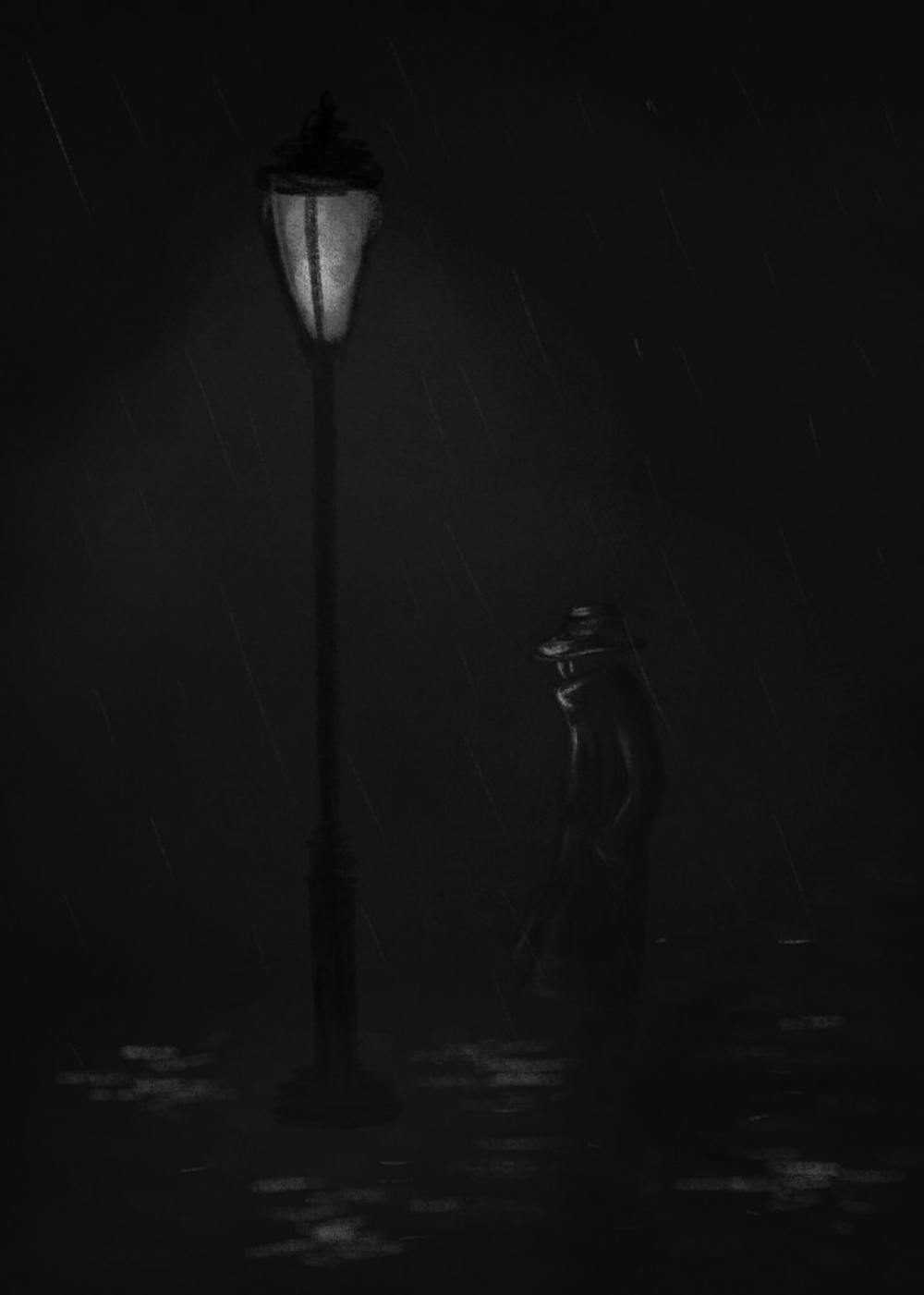

Neo–noir is, in the broadest sense, stylized crime. It’s a derivative of classic film noir, a film style that appeared in the aftermath of World War II in response to the post–war disillusionment that swept through America in the 1940s and '50s. With post–war life came a turning point in on–screen entertainment, and from what was originally meant to spark joy emerged an artistic mirror of the pessimistic American psyche: film noir. Spearheaded by hard–boiled protagonists whose fates often end in death, film noir is characterized by the crime, moral ambiguity, and Dutch angles. Femme fatales also found integral roles in the genre—another response to the societal changes of newfound female independence that struck America during the film noir movement.

The movement ended in the '50s, but film noir hasn’t ever really been laid to rest thanks to the rise of neo–noir. In a debate spanning from the '60s to present–day, neo–noir is questioned in all that it might be: what it’s characterized by, what falls under its umbrella, and how it’s evolved from classic film noir. Generally, neo–noir uses the similar film noir theme of moral ambivalence within an impure protagonist, but the new style flows much more freely, unrestrained by the black–and–white clichés birthed in the '40s and '50s.

Bled over from film noir, neo–noirs are also characterized by social commentary—as such, generations of neo–noir come in waves. Neo–noirs of the '60s relied on the fear and paranoia of the Cold War, the '70s on the distrust of authority following Watergate, and most recently, the fear of terrorism and sense of futility following 9/11.

Of note is Chinatown, starring Jack Nicholson as a classic hard–boiled private investigator who stumbles upon organized corruption within the Los Angeles Department of Water and Power. Given the two–year gap between the film's release (1974) and Watergate (1972), and its own powerful, aging antagonist who gets away with everything in the end, Chinatown clearly subscribes to '70s neo–noir.

Post–9/11 has offered up The Dark Knight (2008) as its defining noir, a film rife with terrorism and unending despair. Batman is a questionable hero, the morally–upright Harvey Dent falls to grief and violence, and the crimes of Gotham City are the products of an ineffective government—The Dark Knight embraces the fears that grip the American public even today.

What makes The Dark Knight and Chinatown “neo” is their fluidity among other styles and genres of film, as well as generational social commentary—The Dark Knight is clearly also a superhero film where Batman, as deplored as he is by the public, still saves the day (to an extent). Blade Runner (1982) is a sci–fi neo–noir about the life and death of slave–based AI, Drive (2011) is a synthwave–fueled neo–noir that throws an unnamed stunt driver into a mafia–related robbery, and Netflix’s A Land Imagined (2018) is a Singaporean neo–noir that sheds light on Singaporean immigrant workers’ slave–like working conditions and the country’s land reclamation efforts. Although all of these films borrow classic noir motifs and traits, none of them fully adhere to the classic style, choosing instead to reach for singularity by blending noir with literally anything else. And that’s why neo–noir is so difficult to concretely define—how much “noir” must a modern film embody to be accurately classified as a neo–noir? A Land Imagined starts as a clear–cut mystery drama that eventually devolves into an extended sequence of surreal soul–searching and dancing—is that neo–noir? I’ll venture a yes—it’s just been highly stylized.

Noirs are dark, bleak, and violent. They are products of their time, reflecting the worries that plague the general public, often after a widespread disaster or tragedy. Why does anybody bother watching these movies if they’re bound to generate some level of existential despair? Because fear and stress are omnipresent in the world around us regardless of how capable you might be at dispelling it, and well–done noirs rip off band–aids of complacency to air out moral dilemmas and unrest through uncomfortable entertainment. Fears should be faced, and that’s what noirs force the viewer to do.