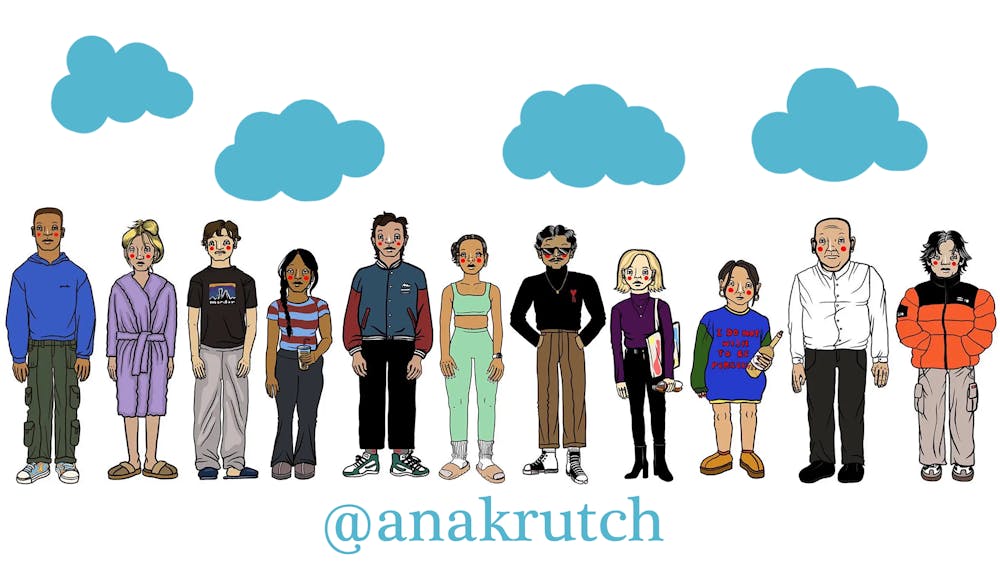

On November 6, 2022, @anakrutch first captured TikTok’s attention with the story of Gilbert, an old man missing his deceased wife. People filled the comments with stories of their own grandparents, or simply their fears of growing old. @Anakrutch’s fictional short stories, at first self–contained, are subtly connected and known for their simple art style and emotionally moving words. Despite publishing videos with no previous following and no hashtags, her account has ballooned to over 200,000 followers and 4 million likes within a month.

Ana Krutchinsky, a former Fintech professional, longtime artist, and the creative voice behind @anakrutch, has always been fascinated by art and visual storytelling. Though the people she writes about are not real, followers have identified with the variety of human emotions and experiences she showcases. She started her page as “a way to objectively look at the way I feel about things, through made–up characters,” she explains. “And the more I did it, the more gratifying it became because I started to realize that all these weird little moments I have, everyone else has too.”

TikTok is known for sparking idealized lifestyle and beauty trends, and like all social media, it’s a space where people showcase the best parts of their lives. Despite the global connectivity TikTok provides, social media in general can be extremely isolating when you’re constantly comparing yourself to everyone else who seems to be living their lives to the fullest.

Krutchinsky’s work is so appealing because of the rare authenticity of her stories—on a platform where it seems like everyone is trying to artistically snapshot their lives into 60–second videos, @anakrutch’s videos spotlight the little moments. She articulates the experiences many of us encounter but don't often talk about—the slow loss of a friendship, missing your parents as you grow older, or even the lonely inkling that you’re no one’s favorite person.

Under each story, people fill the comments with messages affirming these experiences or sharing their own: “How is it possible that I relate to every single one of these?,” “These are sad, but also very human… and I like that.” Ana sees these comments and knows that these stories resonate with her followers. “That’s my favorite part of all this: it opens the door for other people to feel safe,” Ana says.

TikTok’s short video format and soundbites have also made it a frequent platform for storytelling—but not usually in the @anakrutch way. Trauma dumping—which is when strangers (or sometimes, friends) unload their traumatic or stressful experiences on another person without that person’s consent—has frequently been criticized for being bad for people’s mental health, listeners, and sharers alike. Just last month, Street writer Emma Halper analyzed the trend of TikTok users telling dramatic stories accompanied by Nicki Minaj’s song “Super Freaky Girl,” noting that viewers only want to hear the juicy drama of a person’s life, but don’t want to reckon with the emotional fallout that comes with these challenging life experiences.

Moreover, social media influencers are deemed unique from traditional celebrities because of their vulnerability and authenticity. We feel like we know influencers intimately, even though we don’t. When social media users post clickbait videos about breakups or breakdowns, these stories feel real and personal, but often they aren’t. In 2020, communications scholar Evie Psarras utilized the term “emotional camping” to describe the way women on Bravo’s The Real Housewives play up their emotions for the cameras to gain and maintain a following. However, this phenomenon isn’t unique to reality TV personalities. Just think of influencers known for their drama, like Trisha Paytas or Jake Paul. There seems to be a wealth of creators who utilize these same methods to capture audience attention. Because of the distance social media affords between consumers and content creators, there’s no definitive way to distinguish what’s real or what’s for show.

With @anakrutch, it doesn’t matter that the characters we’re relating to are made up. Ana admits she draws from her real–life experiences to inspire her fictional stories because it’s a much less invasive or attention–grabbing form of vulnerability. “I have [a fear] with my page, that if I do this for too long, it stops being authentic,” Ana articulates. “I feel like a lot of writing and poetry ends up becoming about the artists gratifying themselves by putting it out there. I’m trying to stay away from all that and just keep it purely a matter of ‘This is me, do you feel the same?’” While we resonate with the characters Ana invents, we can recognize that these stories are snapshots of fictional lives, and there’s nothing much to be idealized about or overly invested in. These characters are strangers to us, but there is still the comfort of feeling like you know them, that cathartic feeling of finally feeling as if someone out there understands.