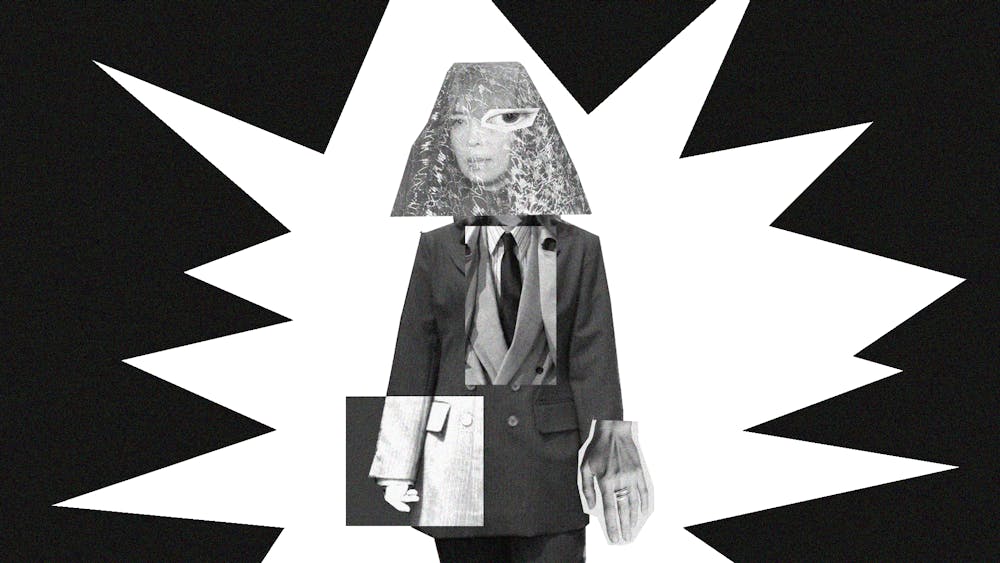

In more ways than one, this past spring was slow to start. Cloudiness stretched through mid–April, winds were too harsh for comfort, and the sun seemed almost afraid to peek out for good. At a glance, the cover for Eiko Ishibashi’s Antigone reflects this same sentiment: a grayscale mass of fog looms over a city like a specter—an immutable force too far to reach but impossible to ignore.

Weaving between genres with remarkable dexterity, Ishibashi has one of the richest musical catalogs of any artist working today. Her work is split in two: there’s a spoken side (which comprises a majority of her early records) featuring expansive, chamber–like art pop and her sweet, airy singing. But she finds even greater comfort in ambient music, an avenue explored through improvisational collaborations, frequent solo output, and, most famously, soundtrack work with filmmaker Ryûsuke Hamaguchi.

Antigone, released at the tail–end of March, is her first return to song–based work in seven years. With new collaborators and soundtrack experience to draw on, it’s one of her most lush efforts yet: a landscape view of reality told in downright hypnotic terms. Backed by collaborator, partner, and experimental legend Jim O’Rourke, as well as instrumentalists like renowned jazz drummer Tatsuhita Yamamoto and accordionist Kalle Moberg, the record paints vivid depictions of a quiet apocalypse.

Compositions like “Coma” and “Trial” move confidently, playfully flourished by repetitive motifs. “Nothing As” and “Continuous Contiguous” are more sedative, piano–led pieces halfway between austere and gorgeously meditative. “October” and “Antigone” pack themselves with cinematic string–led crescendos. “The Model” expands from its slower gait into dramatic electronics—a languid electroacoustic clashing evocative of recent acts like Jockstrap—and maintains intensity over whispered recitations of Michel Foucault. Its final two minutes, a dizzying amalgam of spoken word, field recordings, distant strings, and vocalizations is the closest the record comes to Ishibashi’s ambient output.

The record’s centerpiece, “Mona Lisa”, is particularly moving, and the most strikingly reminiscent of Ishibashi’s work with Hamaguchi. Kei Matsumaro’s hefty sax plays no small role in this, acting as backbone to a ballad swaying as gently and hypnotically as the quotidian shots in films like Hamaguchi’s Evil Does Not Exist. But similar to those films, Ishibashi doesn’t shy from human realities in her music. Like the other tracks, “Mona Lisa”’s lyrics are half–cryptic and half–grounded: “Genocide, glimpsing through each day / Where does the wind go?”

In truth, warfare and cruelty are scattered all over this record. “Demolish in June / The columns rise up / Ashes fall in August / In October, the blood shines,” she sings on “October,” the album’s opener, which references Russia’s 1917 October Revolution. Over a galloping groove on “Trial,” she cuts in, “The fragment of words becomes rain, bombarding the roof / Sound of violence, death is any time now.” Ishibashi is accustomed to facing heavy themes—her last vocal work, 2018’s The Dream My Bones Dream unpacked the history of Manchuria and her family’s past in imperial Japan—but Antigone forgoes specificity. Instead, reality is reconciled as a shapeless but shared grief.

Other songs are less descriptively devastating, but look inward, reflecting on the impotence of contemporary living. The English–sung “Nothing As” feels explicitly helpless: “Nothing as a place to be / A place where you’re not there.” As self–assured as the record sounds, the sadness of living in spite of genocide is overwhelming here—“I take a drink and let it slow me down.”

In Ishibashi’s writing, the grim nature of Antigone is revealed; its namesake, a Greek character whose death at the hands of injustice only causes further tragedy, becomes fitting. In an interview with Kaput Magazin, Ishibashi noted, “I thought the word ‘Antigone’ was a perfect metaphor to connect what happened near me with what is happening far away. We live in a daily struggle. It is the fate of human beings to live in daily conflict in a reality where the two cannot be separated.”

But even still, the album feels hopeful. Lyrics aside, it sounds closer to a wistful Weyes Blood record than anything truly depressing. Ishibashi’s voice remains bright, confident, and earnest throughout. It signals that we can at least find solace in this shared sense of ennui.

I get the chance to watch Ishibashi perform in Fishtown, Pa. the Thursday after Antigone released. On my way to the venue, I re–spin her 2014 record Car and Freezer, half–expecting a show more in line with her more jazz–pop side—I’ve just seen Still House Plants (the coolest band working today) the night before at Solar Myth, and still high on Antigone’s compositions, I’m excited for similarly gripping instrumentation. Although, from my understanding, her live performances have always catered more to electroacoustic performance.

Her show, placed in the intimate red corner of Johnny Brenda’s upper floor, opens with local post–rock and chamber band Hour, whose instrumental set is sweet and not much else. In the break after, I strike up a conversation with a middle–aged man next to me. He had apparently attended Penn in his youth, a punk rock DJ for WXPN (although has some beef with them now, for firing all their student DJs in the ‘90s). We both stand in the front row, equally unsure of what to expect.

When Ishibashi takes the stage, she stands alone in front of her laptop, DJ system, and flute. What follows is a long–form electroacoustic set—nothing like the sound of Antigone. Its soundscapes undulate in intensity, at times growling with urban field recordings and pounding percussion, and in its quietest moments being imbued with an almost arcane energy, contributed by Ishibashi’s droning flute passages flooding the room. On occasion you can hear snippets of news on the television, or at the very least voices in the distance. It’s an earthly element reminiscent of the traffic instructions on “October” or the climax of Evil Does Not Exist, which involves plenty of loudspeaker repetitions.

Melodies are forgone until the set nears its end, when vocals are introduced—but they come nowhere near as committed as they were on Antigone. Instead, Ishibashi’s singing is airy and delicate to a tee, just barely pulsing above its atmospheric bed of flute and synths. It acts, more or less, like a specter, an immutable force facing the crowded Philly venue. Despite aural differences, the scene evokes the same grayscale mass haunting as the city on Antigone’s cover—the same weighty grief of that record which arrives as an unknowable struggle.

While speaking with Kaput, Ishibashi remarked, “I don’t believe that music can solve anything. But I can’t ignore the world when I’m making music.” And despite the vast range of sounds her output covers, from the jazz–ensemble compositions on Antigone to the more reserved, meditative work of her live performances, this ethos comes through clearly. In all its forms, Ishibashi’s work is a moving and delicate space for reflection, and more crucially, resilience in the face of reality.