My parents met through a classic 20th–century matchmaking method: a friend of a friend who thought they would hit it off introduced them. The mutual friend handed over their phone numbers, and one day, my dad picked up the phone, called my mom, and they chose a place to meet up. Now, my generation is obsessed with dating apps—I watch my friends swipe mindlessly, using the same muscle as TikTok doom–scrolling, searching for their match in the endless ether of strangers on Hinge or among the hyper–exclusive pool of potential matches on Raya. Raya’s exclusivity is exhausting, and its waitlist grows by the day. Even the more earnest platforms are designed for dopamine, not depth—they've driven away many users, including 57 percent of women, due to safety concerns. Sure, there are success stories from many of these apps, but what happened to finding your next significant other through a mutual friend?

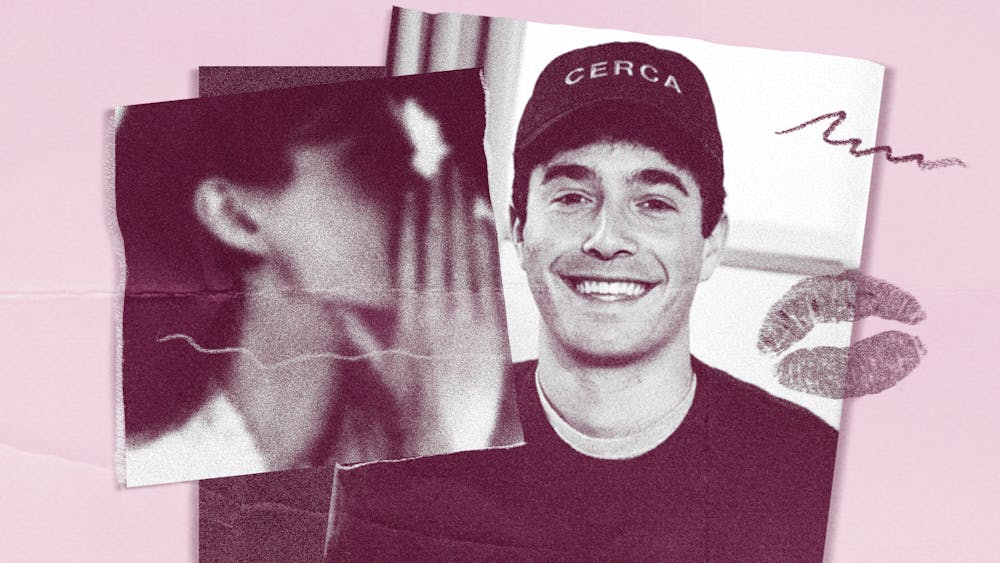

Myles Slayton, a Georgetown ‘25 graduate, had the idea for a new dating app after he and his friends kept striking out on making any meaningful connections. Managing an intense internship in the summer before his senior year, Slayton found himself with very little time to get dressed up and go out, but still hoped for the chance to meet someone in person.

Like his friends, Slayton turned to dating apps for help. “They sucked—except for two good experiences on Hinge,” Slayton says. “I came across a profile of someone I didn’t know, but in one of the pictures, I saw one of my good friends.” That mutual connection gave him the perfect in, and behind the scenes, Slayton’s friend vouched for him. That feeling—of familiarity, safety through verification, and a sense of mutual validation—is what Slayton wanted to replicate for every profile.

During senior year, along with a group of friends, Slayton got to work researching user behaviors and dating app metrics. He found that typical dating app users are on more than one app and that 35% spend over $30 a month on subscriptions. “Clearly, people need help and just aren’t seeing results,” Slayton says. “They don’t hate dating apps. They hate the products out there.” Slayton’s research showed that even though users are burnt out, they still can’t bring themselves to log–out, holding on to the hope that the next swipe could finally be the one. Seeing a promising market opportunity, Slayton and his friends built Cerca, a dating app designed to mirror real life connections by matching users using mutual friends and overlapping social circles.

Cerca modernizes the old–school matchmaking of my parents’ generation, transforming it into a gamified platform designed for Gen Z users. While it is feasible to ask your friends to make the connections for you, people are busy and rarely have the time (or patience) to set their friends up. That’s where Cerca steps in. “You’re on your phone too much to not be able to at least help that process. That’s all Cerca is—it’s just helping that process,” Slayton says. Unlike apps that promote passive swiping though hundreds of profiles a day—leading to fatigue and choice paralysis—Cerca takes a different approach. When users download Cerca, their contacts sync automatically, and each day they are matched with four people—each a real person connected through a mutual.

At launch, Cerca took off among upperclassmen at Georgetown and other college campuses—students who wanted to meet new people but felt like they’d already exhausted their campus social circle. “It was working because you were seeing people on Cerca from your school that you’d never really met or that you’d never really spoken to,” Slayton says. And because of the mutual connection, which ensured that the other person was normal or vetted, users were far more open to meet up with their Cerca match.

Meeting someone from Cerca lets you skip the usual dating app date routine: scouring the internet to find any clues about who they are, stalking their mom’s Facebook, and sending your location to your friends just to feel safe. That’s why Slayton swears by mutual connections, which provide an immediate sense of trust and safety. It also makes people more confident in their matches when they know they have a friend in common. “There’s a lot of BS that you get rid of when your friend—your childhood best friend, your high school best friend, your college best friend—is ready to set you up with someone they know from one of their circles and knows both of you really well,” he says. Mutuals don’t only bring a sense of familiarity and safety; they also ease the awkwardness of a first date, provide shared context to spark a conversation, and create a subtle pressure that makes ghosting before a first date less likely.

As students graduate and move to big cities, they can bring Cerca along with them to help introduce them to people within their extended circles rather than total strangers. For those who may have outgrown their high school or college relationships, Slayton sees particular value in Cerca for young professionals. With most of their days spent in the office, post–grad life leaves them little time to bank on spontaneous bar flirting and hoping it will all work out.

And yes, people are already meeting through the app. “People are dating from Cerca already, and that’s the most powerful thing for us. The app is now expanding to the point [that] the people on the app are [10 degrees of separation away from] myself,” Slayton says.

At a school like Penn, where networking is a sport, it’s no surprise that the same principle applies to dating. Knowing someone in common can help you land an interview—and, as Cerca proves, it can also help you land a first date.