When Melissa Broder’s debut novel The Pisces was published, The New York Times heralded it as “a modern–day myth for women on the verge.” That was seven years ago, when Broder was among the few writers carving a niche with novels that gave voice to the sad girl. Since then, the ‘women–on–the–verge’ genre has only mushroomed (think Miranda July’s All Fours, Otessa Moshfegh’s My Year of Rest and Relaxation, and Mona Awad’s Bunny). The impetus behind the genre—which has its roots in writers like Virginia Woolf, Jean Rhys, and Clarice Lispector—was an earnest quest to portray the raw reality of mental illness in women. Today, it has devolved into a race for female protagonists to ‘out–weird’ each other, each one exhibiting progressively more bizarre behavior with diminishing emotional reality. Readers who once turned to the genre for comfort in their own struggles are now alienated by its catalogue of cultists and cannibals. Broder’s work, however, continues to stand out for its unflagging wit and poignancy, as well as its adherence to emotional truth over literary clickbait.

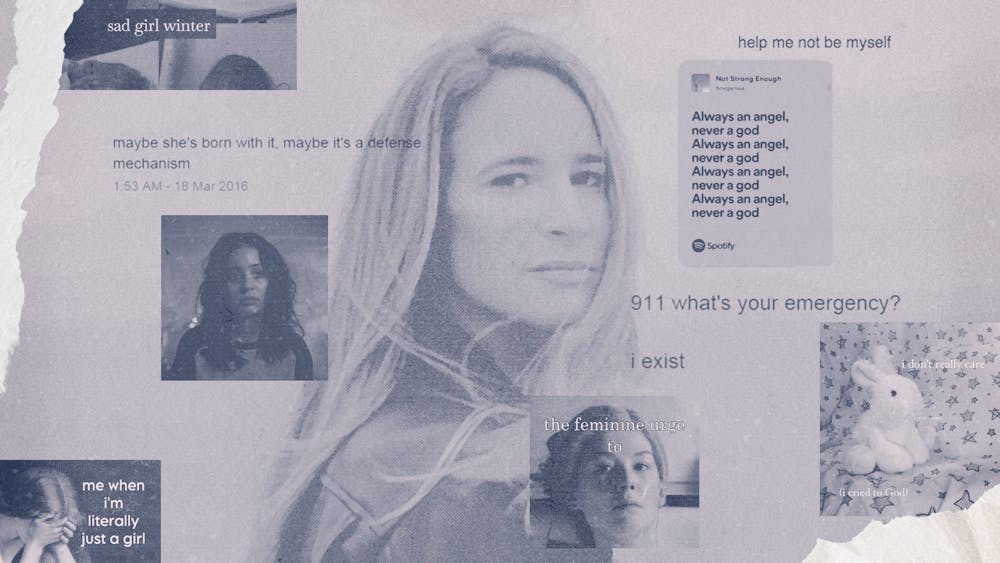

What exactly does Melissa Broder write? Some remember her for a notorious essay about her vomit fetish, others for the X account @SoSadToday, where she launched her career by tweeting about depression. In addition to anonymous tweets, she wrote poetry collections on the subway in New York, from her desk at her office job, and while attending night school to get her Master of Fine Arts. When she moved to Los Angeles, subway rides turned into drives on the highway, typing became voice–to–text dictation, and her poetry transformed into prose, giving rise to the essay collection So Sad Today.

After the essay collection, Broder published three successive novels. In The Pisces, a Ph.D. student falls in love with a merman on Venice Beach. In Milk Fed, a culturally Jewish anorexic girl has a fling with the heavily overweight, Orthodox Jewish girl that serves frozen yogurt at her local store. In Broder’s most recent novel, Death Valley, the narrator wanders into the California desert and communes with past versions of her father, who is inside a cactus. Readers can expect more exploration of the afterlife in Broder’s upcoming book: she won’t reveal the plot, but she tells Street that it will be a comedic story featuring angels, suicidal ideation, and Ralphs supermarket.

No matter how surreal Broder’s writing gets, its heart lies in questions like these:

“What did it mean to love something so much and also be wrong about it? What did it mean to love a version of something that might not really exist, not as you saw it? Did this negate the love? Was the love still real?”

This quotation is an excerpt from Milk Fed, at the opening of a scene in which the narrator debates the history of Israel with the mother of her Orthodox Jewish lover. “That scene,” Broder tells Street, “came from questions I had in all areas. What does it mean to love a nation, but know only one version of its history? What does it mean to love God when God might not be real, or one’s version of God might not be real? What does it mean to love another human being and yet not see them clearly, so that you are loving a projection?”

The narrators of Broder’s novels are tormented by the unknown, be it the question of whether their affections are reciprocated, or the ultimate unknowability of a partner who lives under the sea. This uncertainty only drives her poor characters further into an obsessive love (one might go so far as to use the word limerence). If you turn to Broder’s work, you might be seeking answers about the origins of such a love, or at least a balm to the psychological torture that comes with it. Broder’s credentials include a lifetime of writing and five years of open marriage, but has she untangled the mystery of a crush?

“I’m still wrangling on all levels,” Broder says. “Now I do have more of an understanding of how romantic obsession works neurologically: that there’s an appeal to the unknowable, because it keeps you in that limerence–filled, high–dopamine space. Consider the difference in the feeling of wondering whether someone will text you compared to the feeling of knowing that they definitely will text you. Phones are designed so we stay addicted to them because of that potential. But in my own life, and my writing, I haven’t resolved the question.” In fact, Broder is surprised to hear that fragment of her own writing from Milk Fed repeated back to her: “I was just thinking, ‘I already wrote about that?’ because that’s what I’m writing about right now!”

Broder might not have all the answers, but she certainly knows how to write a good woman–on–the–verge novel. In a gimmicky entry in the genre, the character’s behavior feels outlandish and unrealistic. What makes a good novel, according to Broder, is that “the weirdness of a character’s behavior is earned, propelled by an emotional core which is propelling the outer life of the actors.”

In Broder’s case, this emotional core is drawn from her own experiences: her characters feel so human because they “share her DNA.” If they are depressed and obsessive, it’s because she knows what it’s like to be those things. Perhaps it is this self–knowledge that marks Broder out from other writers in her genre: her willingness to rely on her own experiences, and the honesty with which she dissects them.

Both writers and readers might sometimes wish to expunge their inner sad–girl. Can you write the sad girl out of yourself? According to Broder, no. “I don’t know how much self–awareness saves us,” she says. “It’s amazing on the page, but living in a body is so different to the page. My protagonists get to disappear on the last page, and then I’m still alive grappling with these things. In some ways I think I’ve always been in the same battles, just to different degrees.”

Readers who are familiar with the worry that they could be fighting the same mental battle for the rest of their lives might find in Broder’s words a bleak echo of their worst fears. But that might be exactly what she wants: to show her readers that they are not alone in their fears. Sometimes, those fears can even be turned into something that’s worthy of a laugh.