If you’re sitting at Penn Commons, there is a good chance you'll hear the sounds of skateboarding all around you—plastic wheels rolling against the paved ground or wooden tails snapping against ledges. But across campus, you’ll find signs prohibiting skateboarding, echoing the city’s larger discontent with the sport.

The City of Philadelphia and the skateboarding community have never reached an agreement on how to regulate skating within the city, but Philadelphia has remained a bustling center for the sport. “Over the years, I personally have been harassed, tackled, fined, and had my skateboard taken away countless times by city authorities—all for merely riding my skateboard," says Chad Dravk, owner of Zembo Temple of Skate and Design, a local skateshop. After decades of conflict with the authorities, skaters have launched grassroots efforts to form cultural hubs, like DIY skateparks and skate shops, that have since made Philly an iconic skateboarding city.

One place at the center of this conflict was LOVE Park, an iconic skate spot that was even featured in Tony Hawk’s Pro Skater 2. Skateboarding began there in the 1980s, but later had to contend with a park–specific ban on skateboardingin 1994, a city–wide ban in 2000, and a renovation in 2002 to reduce the number of skateable obstacles. “Even when DC Shoes offered the city $1M to make LOVE Park a skate–friendly plaza … the city said a big NOPE,” Dravk says. The park was later demolished and renovated with some massively redesigns in 2016. To skaters, the loss of LOVE Park, one of the greatest skate spots ever made, was devastating. “With this type of reaction and mentality of the city, this led to skaters building their own parks and spots," Drank explains. "We don't need the help from anyone else; we can just do it—and we have, and will continue.”

Even with their parks being destroyed, Philly skateboarders have proven their resilience time and time again. Stringent city regulations have motivated skaters to build spaces where they belong and fast–tracked the spread of DIY skateparks and street skating culture. Ron Cornwall, owner of Together Skateboarding, a skate and coffee shop located in Brewerytown, explains that skateboarders are “industrious” and “always going to find a way and find a place." “Skateboarders in Philadelphia have fought for skateboarding in Philly all the way through,” Cornwall adds.

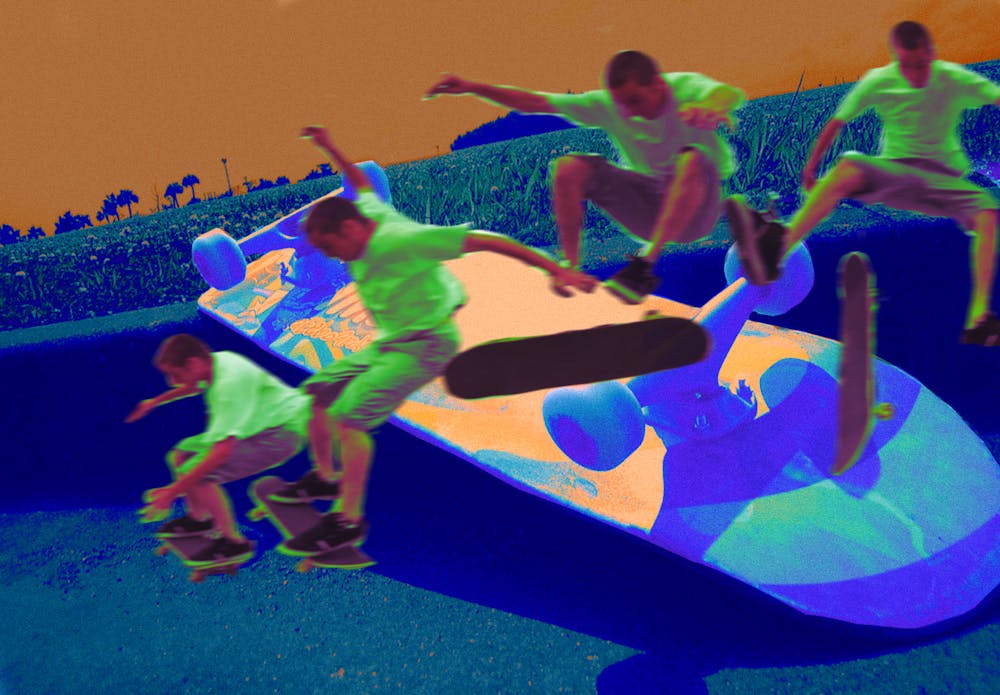

The scene has done more than adapt; it has flourished. The development of DIY skateparks within Philadelphia like 9th and Poplar, Roxborough, and, most importantly, FDR has propelled Philly into its position within skateboarding culture. “In the skateboard world, Philadelphia is a destination city and iconic. It brings people from all over the planet,” says Dravk. FDR Skatepark is located under the overpass of the I–95. Since its start in 1994, it has gained renown for being the largest DIY skatepark in the world. The park began as a way to get skaters out of LOVE Park, but skaters got impatient when the city provided a lackluster space with just a few pyramids and a box. Inspired by DIY parks like Burnside in Portland, skaters began to build their own large–scale obstacles. “What is being built on skater dime, with no public funds or resources, is really impressive. … It's all about earning your place,” Cornwall explains. Not only have Philly skaters had to adapt to strict bylaws, but they've also had to learn to skate in some uniquely tricky place. “Philly streets aren't easy. It's hard. So if you skate hard here, you just get respect; you just get love. Because everyone knows it's fucking hard, you know?”

Cornwall was a TV producer for years in New York, never lost his love for skateboarding, and moved back to Philadelphia to open up Together Skateboarding. “The idea of the coffee part, or the coffee shop, was that we were really interested in building a community,” Cornwall adds. This community has now expanded beyond the impact of the store itself. “Haters showed up, and artists showed up, and musicians showed up, and bankers and developers and neighborhood, and we’re helping to create a place in Brewerytown.” The impact of skaters and skate culture seeps into the fabric of the communities they are in, fostering a sense of connection and creating third spaces for people from all walks of life.

Like many other shops, Together Skateboarding sponsors a few local skaters—nine, to be exact. “It's about being there for them when they land their trick. And celebrating skateboarding,” Cornwall emphasizes.

Dravk similarly founded Zembo as a hub for the community. In the years since founding Zembo, he has set up a lot of skaters’ first boards, built long–lasting relationships with local skaters, and hosted tons of events. “If we sparked the stoke for someone to ride a skateboard, or were an inspiration to be creative/productive, then, to us, we have made an impact,” Dravk says.

Skateboarding has a nuanced and complicated history in Philadelphia, but its effect on the community has been serendipitous. Skaters transcend both legal and physical barriers to their practice, using them as motivation to create spaces of belonging and collaboration. In the end, the best way to support the community and skate culture is to show up. Even if you’ve never stepped on a board before, Ron Cornwall has some advice: “If you're at Penn, don't be afraid to skate because you're a brainiac. Go skate.”