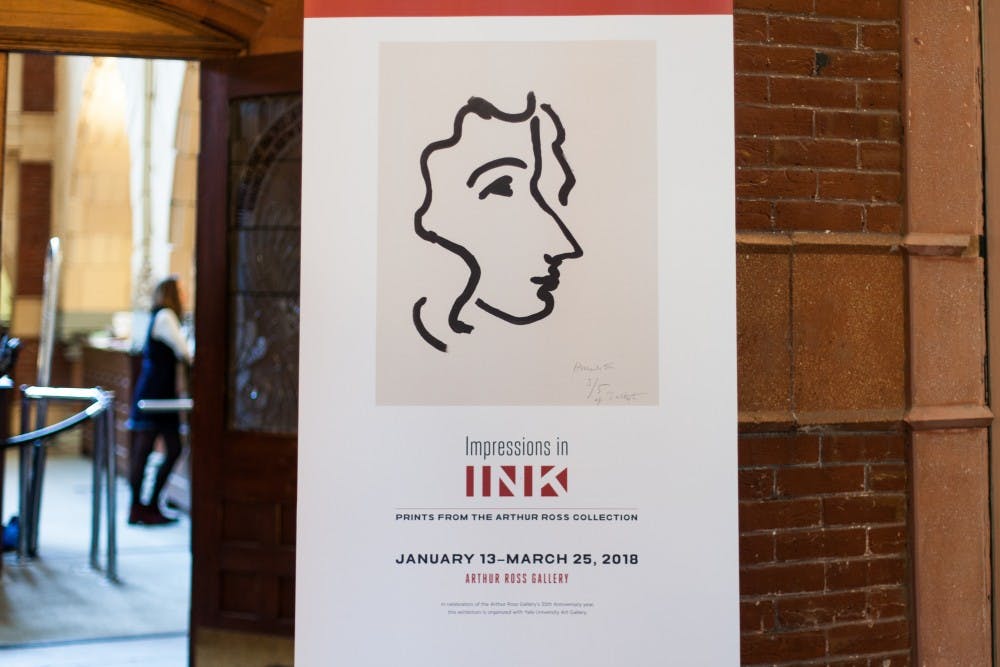

From now until March 25, the Arthur Ross Gallery is hosting Impressions in Ink, an exhibition of prints from artists like Cézanne, Manet, Matisse, and Toulouse–Lautrec.

Prints and printmaking are a form of visual art that is too often overlooked by museum–goers and art history novices. Renowned artists Rembrandt and Durer, for example, were both masters of the printmaking process, but are primarily remembered for their oil paintings. And while painting with oil comes with its own required set of skills, printmaking demands a level of expertise in drawing as well as a familiarity with the chemical and physical properties of the art.

That being said, what makes Impressions in Ink so intriguing is the way in which it displays the signature styles of these artists in a form of media that is rarely seen from them. All but two of the prints in the exhibition are stripped of color, yet each piece is still successful in its artistic effects.

The etchings and lithographs lack a sharpness in minute detail, just as larger impressionist paintings do. Two of Manet’s prints in the exhibition, "The Absinthe Drinker" and "Portrait of Berthe Morisot," reveal the ways in which his style helped advance the art world from realism to impressionism. Both are more focused on the contrast and effect of light on the subjects than with a fully accurate depiction. In the portrait, Morisot’s eyes look almost like smudged dots and the shape of her hat is indistinguishable, yet Manet still successfully communicates her demeanor. Similarly, "The Absinthe Drinker" is one of the darkest prints in the collection with almost the whole image in shadows, but as a result, it effectively displays its subject as someone of questionable character.

Manet is just one of many prominent artists whose style and influence is revealed by the prints of this collection. Two prints by Matisse show his love of line and curvature of figures, an element of his style that is sometimes lost in the loud colors of his signature fauvism. Cézanne’s prints reiterate his obsession with basic shapes, and the way he sees everything as being composed of triangles, squares, and circles. Gauguin’s woodcuts echo his distinct Tahitian paintings that deviated from mainstream impressionism at the time.

Knowing that impressionist paintings are always crowd–pleasers, museums around the world push new, but slightly derivative, exhibitions featuring them every year. And though Impressions in Ink is an examination of that same style, its feature of prints makes it a unique experience. One can only see so many of Monet’s Haystacks before getting tired eyes. This exhibition, particularly in its lack of color and focus on drawn as opposed to painted line, reminds viewers of why impressionism is so popular in the first place for the way even a rough, slightly blurred, colorless sketch can convey the ambiance, effect, and, well, impression of its subject.