“A lot of people think that Native Americans are essentially extinct,” says Connor Beard (C ’21), “I’ve been really struck by the invisibility of Natives on campus.”

Connor identifies as indigenous and is frustrated by this lack of representation of Native Americans. “A goal of mine has been to bring more Native stories to the mainstream,” he says. And for Connor, who has been involved in the performing arts since his freshman year of high school, theatre seemed to be the most natural way to do this.

He, along with the Front Row Theatre Company, decided to bring Manahatta to campus this spring. The play focuses on the story of Jane Snake, a woman from the Lenape Nation in Oklahoma who goes to work for an investment bank in Manhattan. She is the first Native American person to work on Wall Street.

Duval Courteau (C ’20) plays Jane, noting that “she is all about perception. She’s really big on how she is perceived as a Lenape person, by the outside world especially.”

“Jane uses her desire to change the perception of the Lenape people as the main motivator in her career, in her education, in all these things she’s doing,” Duval says, “But we see that Jane, especially in the last scene, has more understanding of what it means to be connected to her past, instead of being hyper–focused on her future.”

“I myself am part Native, so the content of the show just hit home for me right away. It’s so powerful and so universally important,” added Duval.

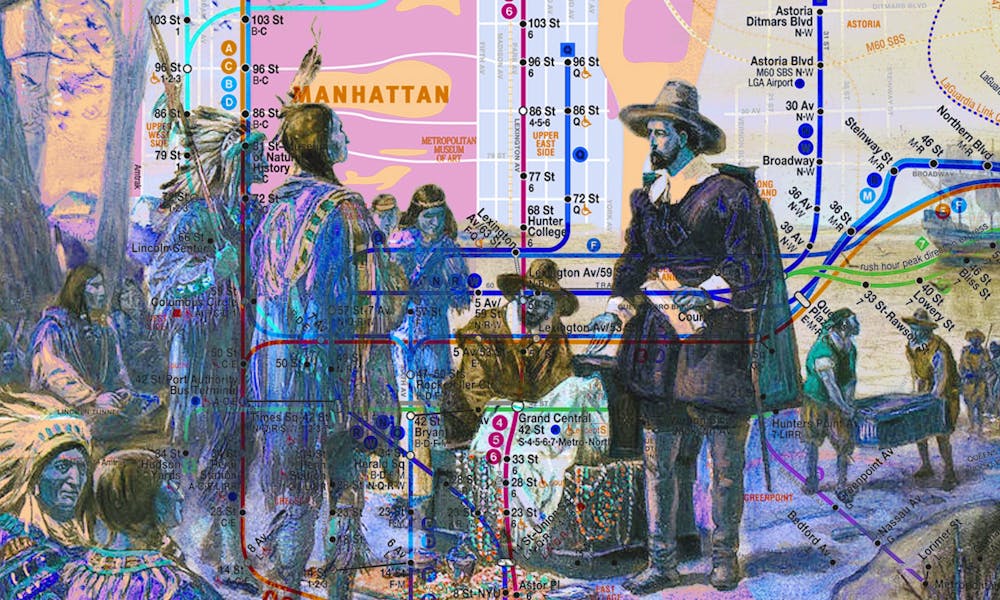

The show contrasts the 2008 financial crisis with the colonial violence perpetrated by settlers and the Dutch East India Company in the 1600s, weaving both narratives together in fluid and dynamic scenes that rapidly flip from one time period to the other. Characters take on two roles: one in the 2008 housing crisis and the other as their 1600s counterpart. Duval believes this fluidity highlights the “strong, strong parallels between the past and the present.”

For David Hernandez (C ’23), Manahatta is his first Penn show. “My whole life I’ve always been the ‘ethnic’ guy in a predominantly white environment. This show having that theme resonated with me personally, which is what compelled me to audition,” David says.

“Each actor plays two characters, one in the past, and one in the present. My character is Luke in the present and Se–ket–tu–may–qua in the past. They’re two very different characters, but they represent the same things.” According to David, both characters are “torn between two worlds”—their Native American roots and the white people with whom they interact frequently.

Luke’s story steeps in this duality. Adopted by a white family and working in their family business, Luke eventually notices that his own people suffer from his actions. Meanwhile, Se–ket–tu–may–qua is a stoic leader who trades with white people at the market. When it comes down to it, both characters must make an important decision between their communities and the expanding, often white, world surrounding them.

Despite occurring over two time periods, the play remains grounded in a consistent theme: the constant violence and oppression faced by Native American communities, and the continuous barriers Native Americans face in white institutions. While the Lenape lose their land to traders, Bobbie, another character, loses her home to overzealous bank mortgages.

In addition, the show offers resilient portraits of Native American women, who are complex characters in their own right equipped with their own perceptions of Native American identity.

Bobbie is played by Mika Graviet (N ’21). “Bobbie is a very strong mother figure. In her tribe as well, the women make all of the decisions,” Mika says, “She’s used to guiding her people and making sure that everyone is kept safe.”

Duval Courteau (left) and Mika Graviet (right) during Manahatta rehearsal. Photo courtesy of Connor Beard.

“In the modern world, all of a sudden, you have this super–spiritual, strong woman thrown into an environment she knows nothing about,” she adds. “She was used to being such a strong character, and all of a sudden she has no idea what’s going on with all the financial verbiage. She’s trying to figure out how to protect herself, her family, and her heritage, when she doesn’t even know how to navigate the world she’s living in now.”

Yet despite these obstacles, Mika says Bobbie “keeps up morale even when she’s losing her home, and what she’s been most familiar with.”

“I had no idea, even about the history of Manhattan, before we even talked about the show. And the fact that we’re on their [Lenape] land. We virtually stole it from them,” Mika says. “To realize all of that is very humbling, and it’s a somber thing.”

Manahatta was written by Mary Kathryn Nagle, who is an enrolled member of the Cherokee Nation of Oklahoma. She currently practices law at Pipestem Law, which specializes in protecting the tribal sovereignty of Native peoples and nations.

Connor explains it was very difficult to find a story he wanted to bring to life as a director and points out that “there’s very little written by or about indigenous people.” In most media, Native Americans are depicted as one–dimensional stereotypes or only pictured in the past.

Connor appreciated that Manahatta showcases Native Americans in the present day. He says, “It feels like that should be a low bar, but I don’t want to show them just in the past. I want to show how indigenous people still exist. They are still around us.”

“In doing this play, there has been so much to unpack and talk about with my cast,” he says. To fully explain the history incorporated in the show, Connor spent hours on research, even meeting with the head of the North American exhibits at the Penn Museum to find sources.

And in just an hour and a half, Nagle manages to discuss a variety of issues faced by Native Americans, such as losing their language and fighting for meager government resources while trying to navigate a purposely complicated system.

While Nagle touches on issues that face most Native American nations, the play itself focuses on the Lenape tribe, which is particularly important considering that Penn’s campus is situated on Lenape land.

Penn was built and continues to stand on Indigenous area known as Lenapehoking, the traditional lands from the Lenape people. In the 1680s, they negotiated with William Penn in the hope of peaceful co–existence. But, as with most stories steeped in the colonial era, relations grew contentious—Thomas Jefferson tricked the Lenape into giving away their land entirely, displacing them.

“Growing up as an indigenous person, this is such a socially relevant issue at all times, but of all tribes, [the play] focuses on the Lenape tribe, whose land we are currently on,” Connor says, “I know Lenape who go to school here.” He says, “This show could not be more relevant for a campus like this that exists on basically stolen ground from the Lenape.”

Despite the play’s contextual relevance and wide net, Connor still finds a personal touch embedded in the narrative. Half Lumbee, a tribe in North Carolina, he feels connected to Jane because he too feels the weight of “paving” the way for other Native American students while recognizing the sacrifices of his ancestors.

“I completely acknowledge that I am white–passing, but I’m still half–Native American and it’s such an important part of who I am. Something that is important in my tribe is education. When we were denied an education in the late 1800s, we actually founded our own university which is now one of the campuses of UNC.” Connor says. “It’s not lost on me that I am not supposed to be here at this university. It wasn’t meant for me. But despite that, I’m here.”

This echoes the last line of Manahatta: “We are still here.” Overall, the play proves a powerful reminder of Native American resilience in the face of centuries of oppression and destruction.

The show will run from Thursday, Feb. 20 to Saturday, Feb. 22, starting at 8 p.m. at the Heyer Sky Lounge in Harrison College House. Tickets are $5 for those with PennCards and $7 for the general public. You can purchase them here.