The morning of February 25, after a restless night for the world, a pencil portrait of Fyodor Dostoevsky leans against the brick wall of the Annenberg Center for the Performing Arts lobby. Dostoevsky was exiled in a Russian prison for being a force of liberal thought and social freedom. Although a century before Vladimir Putin came to power, Dostoevsky's fate, captured in a portrait, is one that's still haunting today. In a similar act of chronological compression, Mark Stockton’s exhibition, 100 People, brings subjects that are generations apart only inches away from one another.

Upon entering the Annenberg lobby, the low, almost extraterrestrial voice of Alice Coltrane is singing through a record player underneath an aged, wooden drawing table. Sketching from an enlarged printed photograph of Coltrane as a reference is Mark Stockton. Stockton is an associate professor at Drexel’s College of Media and Arts and the resident artist in the Arts Lounge at the Annenberg Center. I sat with him as he penciled in the lines of Coltrane’s hair in a homey corner with a bookshelf and oriental rug beneath him.

Stockton’s body of work contemplates the invention of portraiture, which has evolved from paintings that were reserved for those highest in society to the ability to capture a face and make it mass media instantaneously. Stockton asks, “what’s the difference between one portrait versus a lot of portraits?” In America, where society is celebrity-centric and individualistic, our interaction with portraits is almost idolatrous, from hanging them in museums to being on a dollar bill in our wallet.

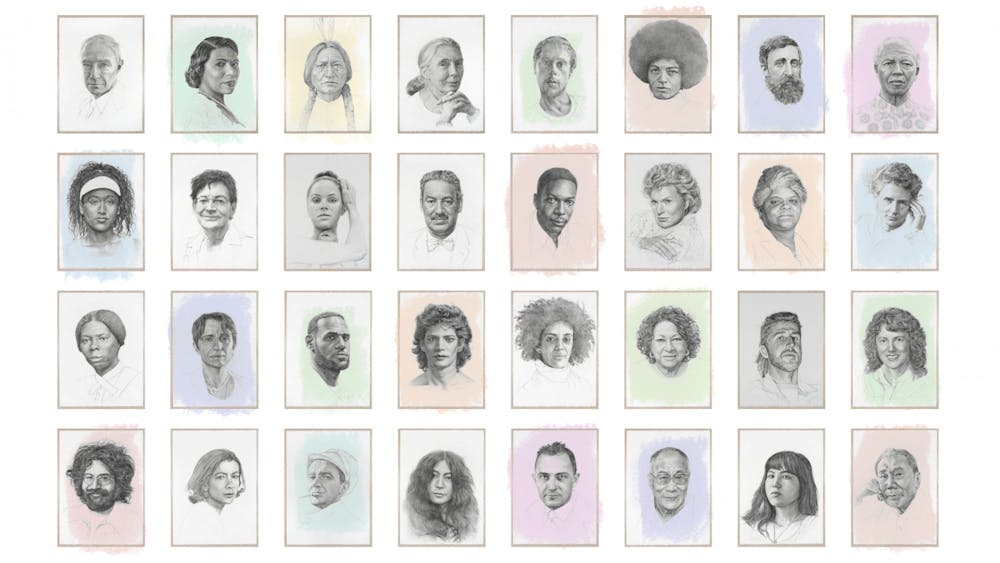

For Stockton, providing the medium of portrait that would have only been available for the upper class to a range of representation across demographics equalizes them. By using a simple pencil, he's humbling the portrait mode into a relatable and accessible format, and hanging them at the same height furthers their “non-hierarchical publication.” Many people question why Stockton doesn't choose to cover his canvases in glass, but the vulnerability and fragility of them, he feels, is what stimulates their humanistic presence.

While looking at an image of the Mona Lisa, perhaps the world's most famous portrait, in an art class, Stockton wondered what made it so timeless, eventually settling on its ability to make eye contact with the viewer. When you see Stockton’s portraits, many parts of his subject’s surrounding body, like their shirt or neck, are only outlined. Their detail becomes more and more concentrated as it centers on their eyes. For Stockton, eye contact with these historical figures offers the most intimate access to them.

After 100 People is complete, Stockton explained how its constituent portraits will be inseparable– no one portrait is on its own, meaning they must travel together. Because of its vast nature, Stockton refers to the project as a “marathon.” He says, “a marathon is not exciting to watch, but it’s more about people enduring and pushing themselves in a longer capacity,” which creates a different type of admiration and investment from its audience.

Stockton believes that the most important role of art should be its capacity to “open it up to communities,” and one of the best effects of his 100 People is its immediate interaction with viewers. When one person recognizes Abraham Lincoln, another may notice Princess Diana instead, then Langston Hughes, Audre Lorde, and so on. Stockton’s artistic language has always consisted of reimagining popular figures, which came from a childhood spent drawing Marvel characters and idealizing athletes on baseball cards.

Since then, Stockton's style has evolved towards working from images— a marriage between his studies in photography, printmaking, and drawing. Shaking off the shavings off his pencil sharpener, he describes the process in a question: “How do you turn an image into a drawing? How do you turn pixel and value into line and shade?” One goal of Stockton’s collection is to reverse the mass-media digitality of people and return them to a “singular fine art.”

As the record finishes, the needle clicking up and the lobby returning to quiet, Stockton, talking about the digitization of most images today, says, “I question its permanence.” Tomorrow, when some new icons appear on the main wall as Stockton swaps them out, they may well outlast their photographic inspiration.

Stockton’s work will be rotating on display until June of 2022.