On Oct. 4, 2020, I began my University–mandated quarantine. The story started with an unexpected positive result from a routine COVID–19 test. My boyfriend received the message while we were ordering breakfast from around the corner. Blissfully unaware. Convinced that it was only minutes until I would test positive too, I spared my eight housemates, packed all my belongings into a duffle bag, and moved in with him.

I never got COVID–19, a fact that prolonged my initial ten–day quarantine into an additional 14–day sentence by myself.

Although I didn’t know it at the time, the University forbids moving between locations during your quarantine. I made what I still think are the right choices, but COVID–19 has made the difference between right and wrong impossible to navigate.

On Oct. 28, 24 days later, I re–entered society. The following is an open letter to the University: a necessary explanation for my transgressions.

Dear Penn,

This experience has been surreal. In years to come, it will all be a story, and I will tell it in rich detail. Thanks to you, I now have primary evidence of my struggle in the desperate year that was 2020. A younger generation of children, hopefully more fair–minded and thoughtful than we could ever hope for them to be, will ask where I was, what I felt, and how I lived during this time. And I will tell them.

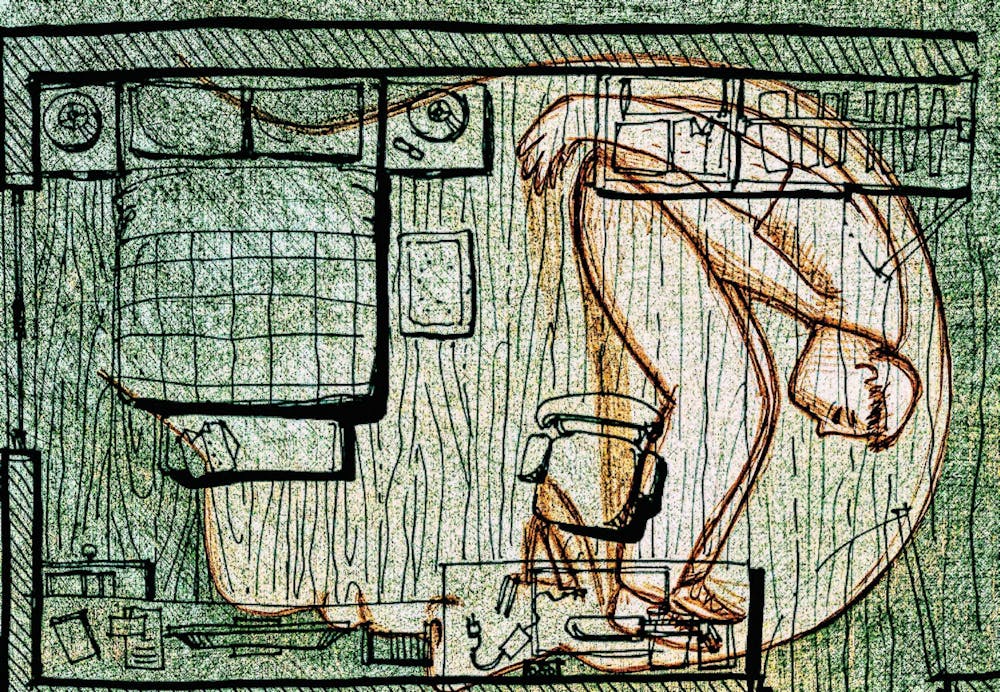

I will tell them that I was quarantined for much of October—waking up each morning to check my temperature and guess whether or not today would be the day that I became sick. That I made a home out of my boyfriend’s half–moved–into room. That we lit candles, ordered groceries, installed a coffee station, created two makeshift desks, spent some days in silence and some days in laughter, pretended we were on vacation as we watched movies and ordered in food, and lived our reality too deeply as we worried about the choices that we were making.

The landscape of my little narrative in a shoebox room will have been threaded and determined, in large part, by the erratic decisions of a fraudulent president who refused to acknowledge a crisis. And so the crisis met me at my door and kicked me out of my house. I will tell them that the political instability of my country touched my life in a way that I had never known was possible; I will think to myself that I hope that the politics of their country touches theirs too, but that they are instead the better for it. The choices of my leaders limited my own opportunities to choose. I became a twentysomething entering a divided society and an unstable job market. I became a girl living in a shoebox room.

I will tell them that my choices before then had been far easier—right had been different from wrong, and sick had been different from well. Systems and institutions were trusted. They were constants in the discordant but repetitive rhythm of life. Somewhere along the lines, the music stopped. As my bedroom became my classroom, my kitchen, and my library, I asked myself: Is this what getting older feels like? Is this the world of my parents? Or is what I am living through a different world altogether—foreign to all of us?

These questions will still be rhetorical when I am grey and old and telling this story. They are unanswerable, but I choose to believe that this is not what getting older is like. I welcome the existence of a world that is different. I choose to go forward. Our ability to hope for a brighter future has not been taken away. And our ability to fight for such a future has not been taken from us either, which is why I understand and I respect your role in this crisis. We are both fighting. We are both living in our own shoebox rooms and exhibiting the infallible nature of the human spirit. I commend your diligence in limiting the spread of a pandemic that I know will only cloud my future more. You’re a part of my story now.

It is unfortunate that I had to give away my October, that words were lost and blame drifted to me, that what I believed to be the right choice did not fit within written policy. I was told otherwise. You were told otherwise. I’ve had to explain myself so much that it feels unreal. Like a character in a story. It only adds to the surrealism.

But for you, it is unfortunate too. It is unfortunate that you must straddle the line between limiting our present and expanding our future. We have so much distrust in each other, and I am sorry for the both of us.

Yet when a younger generation asks about my time in 2020, I will not end my story on “sorry.” I will tell them that for many weeks when I was young, I wore a cotton mask as I walked back from the shower, and that it felt foreign on my clean skin. That I did not think that my life would mirror the dystopian novels I grew up reading. Then I will tell them that when I went out into the bright sunlight without a mask for the first time in weeks and felt the warmth hit my skin, nothing in the world had ever felt better.

I will tell them that no feeling is final, that we control the balance of our lives, that America found a new song to sing, that we voted and danced in the streets, that empathy matters, and that without it we are nothing. That our story does not end in a shoebox room. That it does not end at all.

Best,

Lily Stein