Once a year, Street decides to switch gears and focus our attention on Penn's talented fiction writers. This year, we received many submissions, and although the choice was tough, one piece stood out.

Faryn Pearl | 34th StreetIn American eyes, I guess I’m now officially successful. Four months ago, I was hired by an investment bank. I won’t say which one, since these are difficult economic times. What’s important is that at the same time I began work, memories of past failures and embarrassments began ambushing me daily: a game–saving tackle missed during junior year of high school; my grandfather’s voice saying “Shame on you!” (for what, I don’t remember); a final exam slept through in college; my parents calling in to speak with my kindergarten teacher after I was seen kissing Patrice Robinson behind the dumpster at recess.

The memories show up in the morning and loiter all day. Rather than shoo them off, I dissect them, considering how they might have been avoided. I hate discomfort. Against reason, I still believe that there is a way to get through life without ever experiencing it. My job performance hasn’t been optimal thanks to my meditations, which puts me in a precarious spot: because I’m preoccupied with past failures, I’m in danger of new ones.

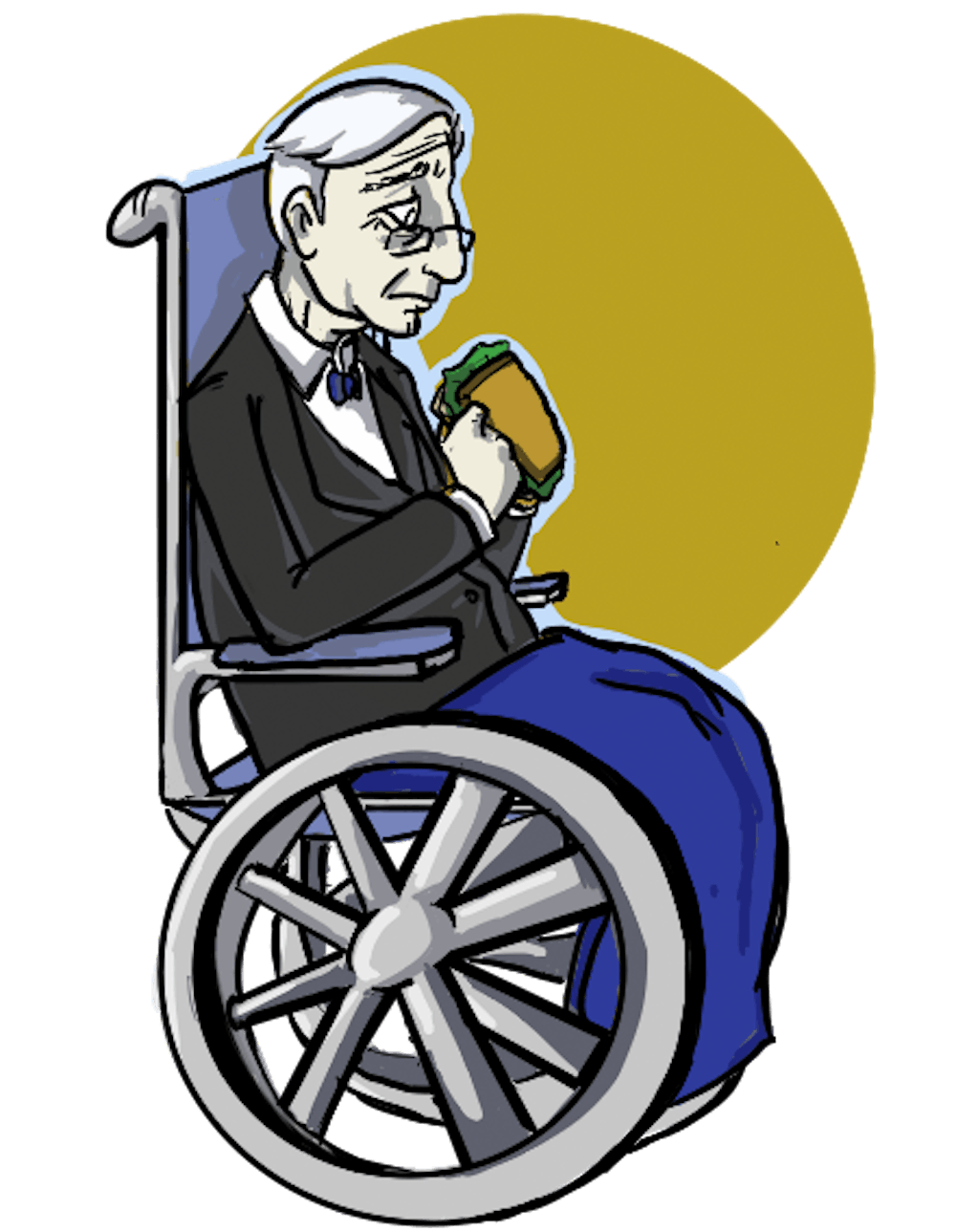

My mind broke the mold the other day: it sent me a memory where I did something right, though it was no less troubling. I was in a quarterly strategy meeting when I saw my grandfather, dressed in an ill–fitting suit (age has twisted and bloated his body so that nothing fits it well anymore) and sitting in his wheel chair. His trembling hands eagerly grasped for a sandwich I’d made him. For an instant, the tectonics of past and present refused to align and I wondered where this scene was from. Then I remembered: my grandmother’s funeral, in November. I’d made my grandfather a sandwich from the platter of cold cuts a friend had brought to the wake.

I doubt I’d thought of that moment since throwing away the crumb–strewn plate after my grandfather had eaten. I began to get choked up. My head felt as if it were being pushed into a vat of petroleum jelly, as my ears dulled with a low roar, my eyes blurred, and my face warmed. The room seemed to fall away from me.

A sympathetic colleague pulled me out of the meeting under the pretense of crunching some numbers and told me to go home and get myself together. And so I descended to the lobby with raincoat and briefcase in hand at an unfamiliar hour. In the afternoon light, the streaks and swirls in the marble walls seemed to depict smoke rising from the burning of Troy.

Unfamiliar with Wednesday afternoons in New York, I took a cab home to Brooklyn, guessing that the mobile desertion of the 3 p.m. train would trouble my raw soul. This was only one obstacle averted. I still had to deal with the unfamiliar silence that prevailed on my street, with the foreign angles of sunlight that filed slowly across my kitchen, the unknown wastes of afternoon television and the anxiety of unanticipated freedom. Inhabiting these typically unobserved hours felt like an intrusion, a destruction of a pristine habitat.

[media-credit id=6671 align="alignleft" width="300"][/media-credit]

And, of course, there was still the memory of my grandfather, which refused to go away. Unlike the recollections of failure, there was nothing for me to fix here, so it floated in my mind bloated and heavy, like a dead fish. I killed two hours with a makeshift coalition of magazines, TV and food. When five o’clock rolled around, I called Jamie, a neighbor I’m friendly with. Jamie works as a production assistant at one of the big networks and we enjoy each other’s company, though not in a way that smacks of any permanence. She’s never told me, but I know from phone calls she’s taken while we’re out at dinner, from plans deferred for vague reasons, that ours is an entanglement of convenience. If we didn’t live on the same block, there would be no reason to carry on as we do.

“Jamie? Did I wake you?”

“Oh… Tom. I’m in London. Program’s regular producer is sick, so here I am.”

“Ah. You didn’t tell me. No problem. Just seeing what you were up to tonight. But I’ll see you when you get back.”

“Mmm. Yes. Everything okay?”

“Yep. Yeah. Everything’s fine.”

“Ok, well I’m going back to bed.”

“Goodbye, Jamie,” I said.

As I pulled the phone from my ear it squawked, “Tom! Tom?”

My heart leaped irrationally. Though I knew Jamie would never profess love or longing for me, I was nevertheless primed to accept any romantic distraction.

“Yes?”

“Would you mind watering my plants? Just ask Alex on the first floor for the key.”

“Sure. I’ll take care of it.”

Two hours later, I’m watching an episode of Band of Brothers I’ve seen at least four times. My grandfather served in Europe, so this probably isn’t the best show for me to watch. Every five minutes or so, I realize I’m totally ignorant of what’s happening on the screen, because I’ve once again been handing my helpless grandfather a cheap sandwich. Around eight thirty, my phone rings and my heart again irrationally reaches for Jamie’s thin offerings. But it is not Jamie. It is Rebecca.

Rebecca and I have known each other since high school, though we followed different orbits back then. We reconnected at a Christmas party back home last year, finding out that we were both headed to New York after graduation. “We’ll hang out,” Rebecca said, and I was surprised to find out that she meant it.

I’m not anti–intellectual by any means. I enjoy literature and don’t mind going to a museum here and there. But I tend to be a bit of a brooder, so I majored in economics because its elegance simplified a messy world, freeing me to spend my days in Providence playing intramural sports and going to bars. I have a knack for the stuff; walking down the street, I often see vectors of exchange imposed on the world. I’ve been reading a bit about the great bebop artists, how they improvised by following the tugs and jerks of the soul upon the mind. That’s not a bad description of how I approach economics; one chord starts vibrating, and I’m off.

But Rebecca is a real intellectual, and very chic on the side. She’s working on her art history doctorate at Columbia and interning at the Whitney. Recently, she cut her hair very short, like Audrey Hepburn in Roman Holiday. Come to think of it, her face is a bit like Audrey’s, with prominent angular bones that would be regal in any other country. I say that I’m surprised she actually wanted to spend time with me, because it seemed we each had the temperament more suited for the other. Despite all her knowledge of theory and metaphysics and such, Rebecca is a breezy person. I don’t mean that she’s insubstantial; far from it. I mean that trouble slides off her like rain off a slicker.

As I said, I’m touched with melancholy. I’ve made it sound like these memories caused an unusual depression, but there’s an excellent chance that this is backward, that my temperament built a nice bridge for these memories to cross. It seems lately that my efforts to live a carefree life, to heap all the pain in the world onto the markets and the laws of supply and demand, have backfired; the more I narrow my vision, the more aware I become of peripheral loomings.

Anyways, it had been about a month since I’d seen Rebecca. I’d gone to a gallery opening with her. It was unclear if it was a date; I’m bad at discerning these things.

“It’s been a while. What are you up to?”

“It has been a while. Sorry; things have been busy. I’m just watching TV. It was a long day.”

“Well, you free tonight?”

“Uh… yeah, but I have another slog tomorrow, so I’ll probably hit the sack soon.”

“Oh, come on, Tom.”

“I’m sorry Rebecca, I just…”

“Right, I’ll see you at the Gatling at nine.”

She hung up. I lingered on the couch for another moment before getting up to change.

I suppose there was a time when a banker like me would have had a hard time in Greenwich Village, but nowadays even the top financial executives wear slim suits and tortoise shell glasses. I’m no exception. I just pick out a few suits and shirts from GQ every few months and I’m free to travel in any circle. This includes a place like the Gatling, a bar done in 19th–century pastiche, a style I’ve noticed gaining popularity lately. I think this has something to do with getting back to a time when machines were vehicles for our wonder, not tiresome cavities on the human spirit. The bartenders all wore waxed handlebar moustaches and sleeve garters. Dandies in checked shirts and velvet jackets filled the room like saplings. I showed up in tweed.

“You look like one of the Whitney’s board members,” Rebecca said with a laugh, by way of greeting.

“And you look like Indiana Jones’s faithful assistant,” I replied, for she wore high–waisted khaki trousers, desert boots and an artfully rumpled denim shirt.

She laughed and kissed my cheek and we sat down. She’d already ordered me a drink, something full of mint. It was odd seeing Rebecca after a month. I wondered what she might want from me and tried to be aloof. She asked about my grandfather, who I’d spoken of at the gallery, and I said he was fine. She asked about my parents; I said they were fine. She asked what I’d been doing, and I said not much.

“How about work?” she asked. “You said you had a long day. Working on a merger or something?”

“And that threw you off?” she asked, interested. “I mean, I don’t want to discount your feelings but… it’s kind of an emotionally uncharged action.”

“I know, I know. I think it’s got something to do with… well. Look. I’m here, making a significant amount of money for someone my age. And all I can think about is my grandmother’s body lying underground. It doesn’t seem final; I keep thinking she’s conscious down there.”

“Come on, Tom. That’s morbid.”

“But there’s more. My grandpa, he’s not doing well back home. I’m just out here making a load of money so that I can go back to school and get my PhD so I can teach and not work at a bank. 3,000 people working in that building and I guarantee I’m the only one who stops and asks why we’re doing what we do, just making money out of money, so that maybe we can retire when we’re 30. And then what? Pass time until we die, that’s the real answer.”

Rebecca looked disappointed.

“That’s really quite morose. No way to live, Tom.”

“I know it. But I can’t help it. I was reading National Geographic at the barbershop the other day. There was an article about what the end of the world will look like. Why do they have to do that? Or that artist, what’s his name… the one who made a sculpture of JFK on the autopsy table? Just lying there with his head looking like one of those butter cookies with jam in the middle. Any kid could go see that in a museum. You’re the art scholar. Can you explain that one to me?”

“I can, but I won’t right now.”

She set down her drink. Pulling a pen from her purse, she began writing on a napkin.

“There’s something I almost got tattooed on my arm,” she said. “But I didn’t like the idea of writing on my body like that. It’s something Kafka said. You’ve got to see it written out.”

She turned the napkin towards me. It read:

THERE IS AN INFINITE AMOUNT OF HOPE IN THE UNIVERSE, BUT NOT FOR US.

I raised my eyebrows.

“Is that supposed to make me feel better?”

She met my gaze, and then we both began to laugh.

Outside, it was warm. Spring was catching its stride. In the purple twilight, the breeze carried the scent of chlorophyll to my nostrils, headier than the drink I’d had inside. We walked to Rebecca’s subway stop at the end of the block, and paused with silent smiles.

“Look, call me soon. Let’s hang out more than once a month. Stop all this JFK autopsy nonsense.”

“I will,” I said, and she kissed me on the forehead and started down the steps.

The darkened maw of the subway breathed a mossy death–smell. In her chic archaeologist getup, it wasn’t difficult to imagine Rebecca descending into King Tut’s tomb. For a moment, absurdly, I feared for her, and wanted to call out to her to return.

“Rebecca,” I said, and she stopped and turned.

I hurried down the few steps between us.

“My grandpa’s birthday is at the end of the month. I’m going to go see him. Come to Milwaukee with me?”

Before she said yes, she fixed me with a smile.