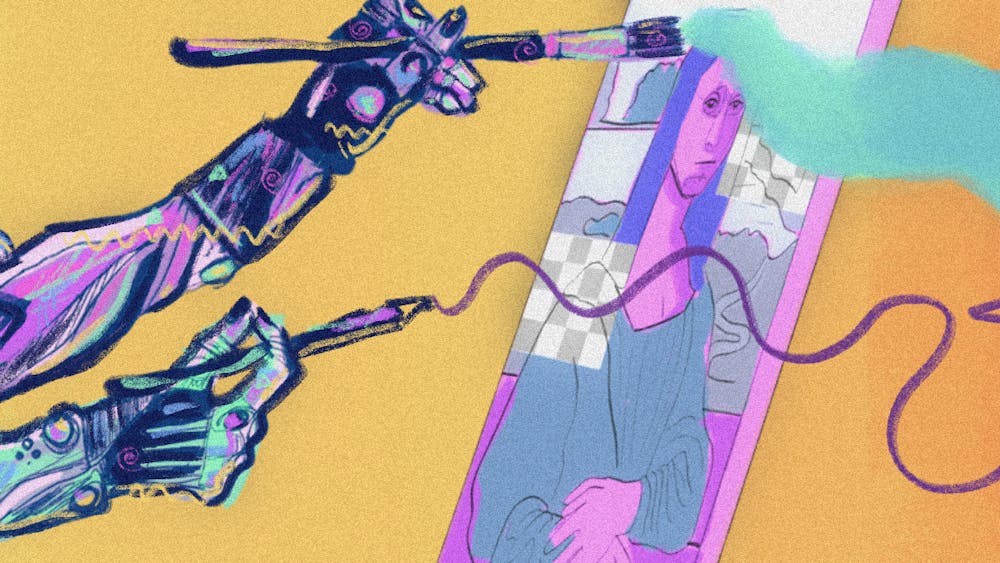

There’s no way around it. You live in a world where Drake songs can be recorded without Drake, paintings are born from DALL–E prompts, and ChatGPT will write an apology text to your girlfriend.

Professors flounder when trying to parcel student’s work from that of a software formula. Jobs you’d hoped to apply for are slowly being replaced by computers.

In your day–to–day life, you might be forced to wonder whether you could have finished your paper without ChatGPT, or if Barack Obama really did get a verse on Ice Spice’s “Princess Diana”—it was amazing, and though deep down you know the truth, you choose to believe it was not just another TikTok scam.

There is no doubt, though, that AI has radically altered the way you consume art. Music, writing, design, painting, sculpting, and more—there is no longer the guarantee of a human person behind it all.

And so when an AI Obama/Ice Spice collab poses an artistic existential conundrum, it’s time to ask for expert opinion. Luckily, Penn’s own J.D. Porter, a Digital Humanities specialist at the Price Lab, and English professor James English, founding faculty director of the Price Lab, were happy to help.

English sets the boundary that talking about art and AI would require two separate conversations. One for commercial art, the other for ‘high’ art, or art for art’s sake.

The scope of commercial art includes anything from advertising to designing book covers, auto–mechanical manuals, and logos to writing a Netflix series or drawing postcards. Because most of this work is built on precedent—that is, the artistic product is more or less formulaic and is expected to remain within the ballpark of what is trending or has already been done—it is work that can be replaced by AI.

English admits, “For me, that’s the dystopian part, that AI is replacing a lot of labor done by skilled people. And these are people like my son and my students. Even my mom was an artist. I feel the pain there.”

As the clumsiness of AI artistic reproductions disappears over the next few years, as both Porter and English predict, the artistic laborers will no longer be able to boast quality over AI’s speed and cost–saving allure. Soon, the only difference between a graphic designer and AI will be that AI won’t ask for a raise. Or any salary at all for that matter.

When AI masters imitation of these kinds of replicable products, putting out Hallmark movies and greeting cards as well as human writers and painters do, “there’s no point of trying to defend some notion of beauty that’s inherent in the objects [created by people]” says English. If one understands art as a purely aesthetic and material process, then AI’s mastery here would seem enough to qualify it as genuinely artistic.

Whether we protect human commercial artists will ultimately be a matter of whether governments and companies will sacrifice lower production costs in favor of the broader societal value of employing real people. To create or not create with AI is “a political decision, in a way, rather than an aesthetic one” says Porter.

When we consider the field of ars gratia artis though, any art beyond the scope of industry becomes a social decision. Here, we are talking about the transference of emotion and human experience that slides between the artist, the work of art, and the audience. English described the phenomenon of artistic magic—a sort of glow or aura surrounding a special creative work—not as a product of the art’s physical qualities, but as projections of feeling from the people involved in creating and experiencing the piece. Essentially, we’re talking about art as a mode of communication: the idea that the audience finds meaning in a work or an oeuvre because they approach it with the knowledge that it was made, with an intentional vision and personal care, by someone else.

“The art world is a social thing … Yes, AI is imitating material and aesthetic things in various ways, and it might do that quite skillfully, but it really doesn’t care about the social surroundings, the social situation, the outside world. And that’s where the action happens in Art, with a capital A,” English says.

Consider, for example, a wedding vow. Even if AI could write perfectly fine or even really impressive prose, its vow will necessarily mean less than one written by one’s partner. Alas, the Achilles' heel of AI: no matter how well it can replicate material art, AI will never be able to access the system of social dynamics that surrounds creative production and which truly makes art meaningful to others.

Porter argued the importance of this human involvement through artist Marcel Duchamp’s urinal, which, in fact, was just an exhibit of his signed urinal. Still, he meant the piece to be something radical to comment on the pretentious and exclusionary nature of the art world in the 1920s, and in this way, he gave artistic life to an inanimate object.

“Duchamp had intention about it. He gave meaning to the urinal, he made it stand for something. AI could reproduce a toilet, and sign it too, but it could not infuse behind it a revolutionary meaning,” Porter says.

Thinking of the revolutionary and the avant–garde, English takes it further. “I can't really see how AI would have produced the profound first work, you know, the first Duchampian gesture. Because that’s something that comes from left field, and an AI can’t come from left field. AI is better at imitation with small differences than it is at radical newness.”

Or as Porter put it, “These things can’t make something unprecedented because what they are are big precedent machines, right?” By this he means that because AI works from its input base of existing paintings, uses of language, and so on, it doesn’t have the faculties to innovate.

And so it seems humans still have a monopoly on the radical—on the left–field, the revolutionary, and the truly meaningful. At the very least, we still corner the market on communicative art, subversive urinals, and wedding vows.

Porter and English admitted, though, they might not be able to say the same for a Hallmark movie.