Châtelet–Les Halles (1e)

"Stop! If a church is open, I always enter."

We’re in front of Saint–Eustache, freshly back from a date at the Brancusi Atelier and heading to his motorbike. Throngs of tourists are swirling around us. I’m not too impressed by this sudden show of piety, or by his follow–up question, pitched with a grin:

"Have you been in love before?" As if!

Weaving between pedestrians, we find his Lambretta. I hop on and ride pillion as he steers us through traffic, taking us along the Left Bank and driving past embassies and posh schools until we arrive in the 15th, onetime home of Brigitte Bardot and Samuel Beckett.

Upstairs, we go out on the porch. We talk about quitting, so I try a feeble joke—"one only stops smoking so one can start again"—but he won’t even smile.

He loves the same artists I do, which is cause for concern. I like old pigs and perverts: Bacon, Picasso, Schiele, and the lot. Time passes until he lifts me onto the bed and corners me with the typical nonsense—it’s now or never or some drivel. Wannabe Don Juan.

I pluck my ballerinas from the doormat and slip away into the street, walk all the way home to République, woozy from wine. On the way I pass the Eiffel Tower, happy families picnicking below, cross the bridge and like an idiot wind up in Place de la Concorde again, trapped between cars that won’t stop. I’ve been here over and over, but I’m still so green.

Château de Vincennes (12e)

This time he’s Ukrainian, a former ballet dancer. We meet at an exhibition opening for exiled artists. I’m swept and he’s swept too, so we make a date to walk in the woods. He lets slip a few dates and I calculate that he’s 35, give or take.

We talk about drink and dance and wartime and exile. We talk about Eastern Europe and my studies. "You don’t seem to understand," he says. "If there’s one word I have for you, it’s freedom. You have all the freedom a person could hope for."

Corentin Cariou (19e)

Maria and I take the 7 up north to La Villette. Before we get on, the light on the noticeboard flickers and changes: our train will be late by a quarter hour.

"Fucking delay! This line is always delayed. Some crazy flinging himself onto the rails again."

Maria and I meet six months later and slip away to Verona without telling anyone. Somehow my mother finds out and rages and rages—but we come back safe and sound. Maria hosts a party to celebrate, 20 people in her studio, red wine and her mother’s homemade Patxaran splashing onto the white walls. Next morning, we scrub purple stains from ceiling to parquet.

Reuilly-Diderot (12e)

When I’m at my lowest—when I want to tear my eyes out and bludgeon my hands so I can never work again—Baltazár takes me in.

I was the thinnest I’d ever been. All I’d brought with me that winter was a threadbare coat. Such a sorry sight, you would’ve thought I was a victim of the Vaganova method.

When I arrive he feeds me so much food I think I’ll burst. On the way home from the Tuileries I need to vomit. I need to vomit but we’re on the metro and there’s nowhere to run. So I sit down and he shields me with his coat.

Stalingrad (10e)

He’s an old friend whose mother and father fled the same rotten town as mine: Kaposvár, where the hanging tree and the music school stand next to each other. When I visit the family for the first time, I’m only 13. We nip down to the superette for eggs and he introduces me to the Maghrebi shopkeeper as his little cousin. I go red.

We don’t meet again until this summer. I’m twenty and he fails to recognize me. Then someone speaks my name and we take each other in like spring bulbs hitting the air for the first time. And I remember what his mother said all those years ago, smoking in the kitchen: "Love is only weakness."

She shouldn’t smoke anymore and neither should I. But this summer she nips some of my tobacco when everyone else has gone to bed. We sit at the dinner table and smoke our shitty little darts, two chimney pots together in the quiet.

Gare du Nord (10e)

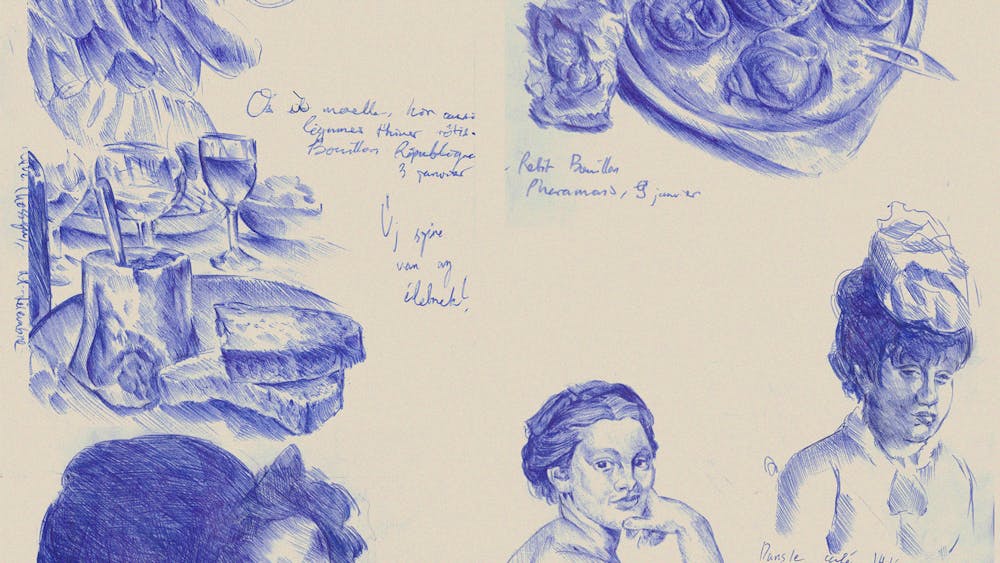

On the way back to London on the Eurostar, I examine all my ballpoints. I’ve shown them only to a handful of people. This boy, the latest, is a Paris native. He likes Diderot and Tocqueville and all the ones I seem to hate. But these days I think hate could be the wellspring of curiosity, or something like desire.

I show him my impression of the two little dragons roosting on the side of the Fontaine Saint–Michel. When he sees them on his walk he remembers to send a photo. There’s never a beginning or end. Only a station and a rattling cart and some passengers who cross each other time and time again.